Available Through Bookfinder.com:

http://ditillo2.blogspot.ca/2017/06/the-body-built-part-one-kenneth-dutton.html

THE FAUN: SANSONE

Until the 1930s, most of the practitioners of bodybuilding were also weightlifters, usually making their living from theatrical and circus performances and instruction in physical culture. Their bodybuilding activity, in the form of posing, remained a part of their stage act as it had done for Sandow, or took the form of posing for photographic studies to be used as promotional material.

Men like Max Sick of Bavaria (who called himself Maxick) -

Men like Max Sick of Bavaria (who called himself Maxick) -

An Abdominal Isolation by Maxick

Similar Isolation by Bishnu Gosh

Treloar's pupil Orville Stamm ('the boy Hercules'), and Georg Hackenschmidt ('the Russian Lion') were essentially stage weightlifters, though all had themselves posing in skimpy attire.

Orville Stamm

Gradually, however, as the vaudeville theater declined in popularity, the 'strongman' stage act became a less lucrative way of making a living and its exponents could no longer earn the salary of a Cabinet Minister. At the same time, weight-training techniques were becoming more sophisticated: by 1920 weightlifting had become an Olympic sport, and its practitioners had discovered that the type of training required for building massive strength was different from that required for achieving a muscular look. Posing in the near-nude seemed, in any case, far too frivolous and 'arty' an activity for serious international sportsmen.

The transition from bodybuilding as an adjunct to weightlifting to its emergence as an autonomous activity took some years. Despite the public fascination with Sandow's 'physical perfection', he remained until his de4ath in 1925 the symbol of the strong man as much as that of the developed man. It took a gradual shift in perspective for the representational interest of the body to free itself in the public mind from its instrumental function - a shift which has never been totally accepted in the community at large and which even today leads to the popular criticism that bodybuilders are not actually strong and that their muscularity is 'useless'.

This shift in the nature of bodybuilding from a by-product of the body's instrumental use in weightlifting and health-oriented physical culture to a distinct form of representational display took place in the years following Sandow's death, in the later 1920s and early 1930s. The increasing sophistication of public taste was seized upon by a number of influential trainers and photographers who placed a new emphasis on the formal aesthetic quality of the posed figure. Amongst the bodybuilders and trainers was the man whom many considered Sandow's natural successor, Sigmund Klein (1902-1987).

Steve Reeves and Sigmund Klein

Sig Klein, cover of Roger Eells "Vim" magazine.

The magazine, with Eells as editor, ran for 17 issues.

Here is a 17-part series "My First Quarter-Century in the Iron Game" by Klein:

Sweet Mystic 17, eh. The magic of ten and seven. Senseless numerical balderdash aplenty, mate.

Klein had been brought from Germany as a young child to live in the USA where he observed the vaudeville strongmen and followed for a time in their footsteps. Having married the daughter of 'Professor Attila', he re-opened the Attila gymnasium before beginning his own physical culture studio in 1926. In his instruction and numerous magazine articles, including those in his own publication -

Klein's Bell ran for 19 issues.

Throughout, he was to place the primary emphasis on what he called 'training for shape', developing and teaching the types of exerciser that would bring out the musculature of the body as distinct from increasing its strength. Frequently photographed in bodybuilder's trunks or brief 'posing strap', he embodied in his own physical development and passed on to his pupils a much more exclusive concern with the aesthetics of muscularity than the 'professors' of physical culture (including Sandow) had traditionally fostered.

Without skillful and sympathetic photographers, however, bodybuilding could not have extended its appeal beyond a small number of devotees. A number of early professional photographers (Sarony, Eisenmann) had made something of a specialty of 'strongman' photographs.

- Note: Eisenmann also extensively photographed those who were well known in that era's 'Freak Shows' as well. Some amazing photos, no question. The concept, perception and definition of 'ugly' is a fascinating subject, and it relates strongly to the idea of masculine beauty and the physique over time.

Very interesting, well researched, well written and well presented book on the subject:

"Ugliness: A Cultural History" by Gretchen E. Henderson (2015)

It was not until the 1920s that there emerged a new group who devoted themselves to what became known as 'physique photography or the photographic depiction of 'expressive posing'. The first of these was John M. Hernic, a former bodybuilder who in the 1920s opened a mail order photographic gallery which sold 'The Apollo Art Studies' featuring the leading bodybuilders of his time.

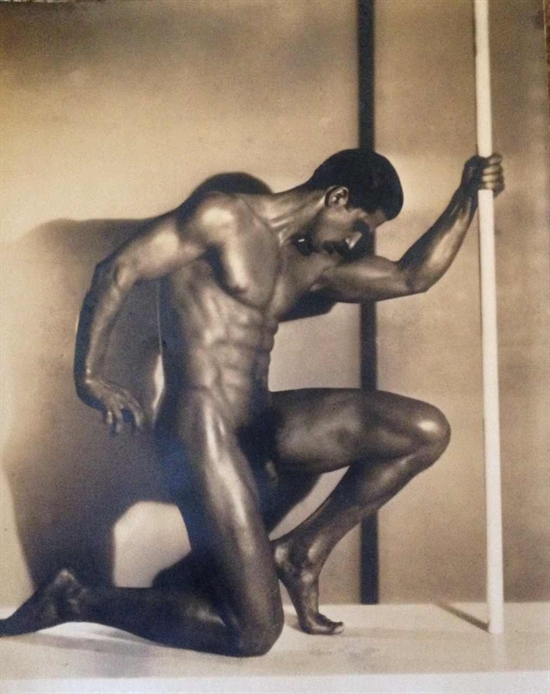

The most accomplished of early physique photographers was Edwin F. Townsend of New York, who did away with the pseudo-classical props of the earlier generation and posed his models in relaxed or balletic rather than heroic attitudes. Sophisticated lighting, rich finishing and a meticulous concern for detail made Townsend's work stand out in sharp contrast to the often crude products of his predecessors. The historian David Chapman has commented that:

"Townsend often printed his photographs in sepia tone and softened the focus to make his subjects more romantic and dreamy looking. He apparently liked the contrast between the vague, almost feminine image and the hard masculinity of the subject. So while Saxony viewed hi subjects as characters in a cosmic drama, Townsend tended to see his as idealized versions of perfection unconnected with the world around them."

Townsend produced some elegant studies of Sigmund Klein in 1921, but it was some years later that his most memorable work was done - a series of poses by his favorite model Tony Sansone. These not only made his own reputation but did much to re-establish the developed male body as an object of aesthetic contemplation after its abandonment by the world of high art.

The most accomplished of early physique photographers was Edwin F. Townsend of New York, who did away with the pseudo-classical props of the earlier generation and posed his models in relaxed or balletic rather than heroic attitudes. Sophisticated lighting, rich finishing and a meticulous concern for detail made Townsend's work stand out in sharp contrast to the often crude products of his predecessors. The historian David Chapman has commented that:

"Townsend often printed his photographs in sepia tone and softened the focus to make his subjects more romantic and dreamy looking. He apparently liked the contrast between the vague, almost feminine image and the hard masculinity of the subject. So while Saxony viewed hi subjects as characters in a cosmic drama, Townsend tended to see his as idealized versions of perfection unconnected with the world around them."

Townsend produced some elegant studies of Sigmund Klein in 1921, but it was some years later that his most memorable work was done - a series of poses by his favorite model Tony Sansone. These not only made his own reputation but did much to re-establish the developed male body as an object of aesthetic contemplation after its abandonment by the world of high art.

Edwin F. Townsend - from "Rhythm"

Circa 1935, model Tony Sansone.

None of his predecessors in the field, however accomplished, had produced work of such beauty of composition, which at times matches in visual power the contemporaneous nudes of the internationally famous Edward Weston and prefigures those of Bruce Weber and Robert Mapplethorpe in more recent years.

It was not only Townsend's reputation that was made by these studies, but even more so that of his model. Tony Sansone (1905-1987) was a native of New York who had attempted to overcome a number of childhood illnesses by taking up athletics and physical culture. Inspired by photographs of well-developed bodies in Physical Culture magazine, he began to take an interest in bodybuilding, and a chance encounter with Charles Atlas on the beach in Coney Island in 1921 led him to follow the Charles Atlas Course.

By the following year he had won an Atlas contest for progress and development and the for the next few years dedicated himself passionately to bodybuilding.

Having worked for a short time as an actor and dancer, he later chose to devote his career to the instruction of others in bodybuilding, and in his mature years operated three different gymnasiums in the Manhattan area.

Having worked for a short time as an actor and dancer, he later chose to devote his career to the instruction of others in bodybuilding, and in his mature years operated three different gymnasiums in the Manhattan area.

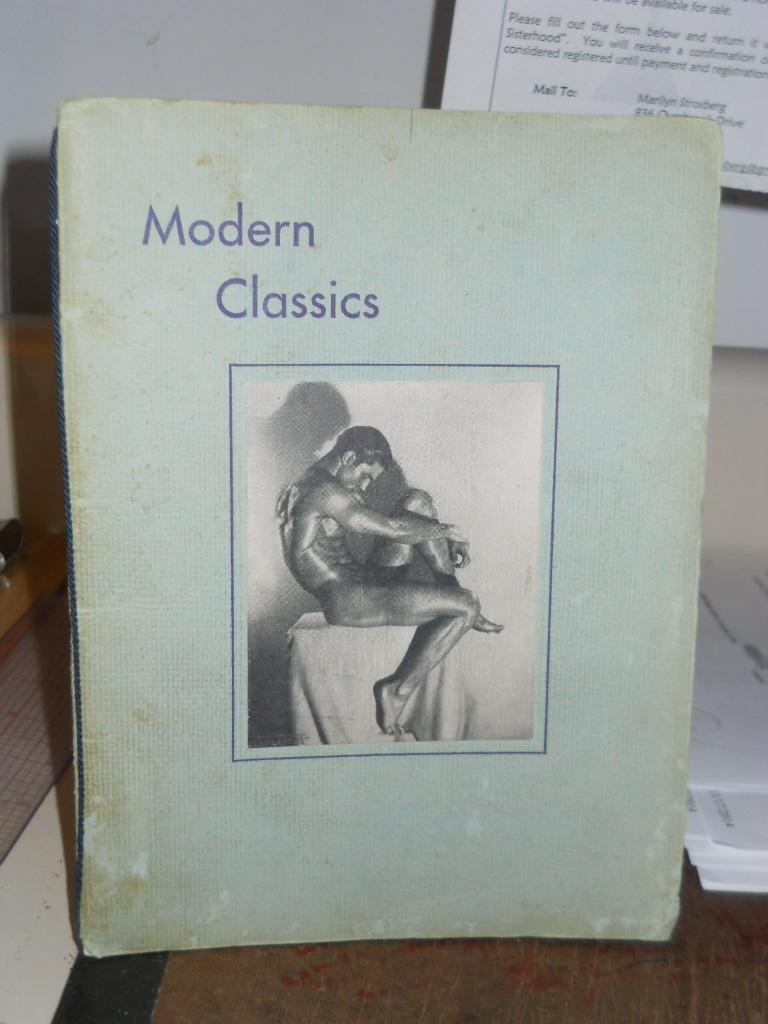

Sansone's place in the history of the physique rests on two slender volumes of photographs, Modern Classics (1932) and Rhythm (1935).

bookfinder.com

Volpe Photo of Sansone

Mainly by Townsend, though with some by Achille Volpe, they show the athlete posed against a simple background, either almost black (only a dimly lit wall and curtain breaking up the space) or almost white (the shadow of his body reflecting his pose). His body is sometimes relaxed - recumbent, seated or standing casually - sometime taut, a simple prop suggesting an antique theme. (David) Chapman rightly speaks of the 'cool and elegant detachment' of these poses, the serenity which draws upon 'images of a Classical and contemplative Elysium of the soul'.

What is it that gives these two relatively meager collections of photographs such an important documentary status in the social history of the body and that makes Sansone such a significant figure despite the totally unremarkable nature of his public career? There are at least three aspects of this question which deserve our attention.

First, these are for the most part nude photographs. From Sandow's time until the end of the 1930s, it was by no means uncommon for bodybuilders to be photographed nude, though only from an angle at which the genitals were hidden. The body was either turned away from the camera, or photographed from the side so that the near leg could be placed forward of the body and conceal the genital area. In a frontal shot, the model (if not wearing any tights, trunks or some other form of clothing) was required to sport the somewhat ridiculous 'fig leaf' in order that modesty should be preserved. (Though Sandow's plaster cast for the British Museum shows totally nude including genitals, this could no doubt have been justified on 'scientific' grounds.) In the case of Sansone, however, the genital area is often completely visible, no attempt being made to conceal it by an artificially adopted pose.

The circulation of the photographs in their original form was highly restricted. In the two volumes in which they were published the genital area was carefully airbrushed, giving it the appearance of a black triangle of hair which is curiously, and disconcertingly, similar to that of the female pubic region.

In other versions subsequently reproduced, a fig-leaf has been painted on in the appropriate spot - like air-brushing, a common practice of the time as was the addition of a painted 'posing pouch' or G-string. Air-brushed or not, Sansone was clearly intended to be seen as a nude figure - and, in many of the photographs, a nude figure in repose. The classical vocabulary of stage props had disappeared, but so too had the equally classical reference-frame of the defiant heroic stance which was part of the justification for the nudity of the subject. Never before had the image of the bodybuilder been handled with such voluptuousness, or come so close to an overtly erotic treatment.

The second important factor is Sansone's renowned handsomeness. A man of striking visual beauty, he was so remarked for his 'sultry Latin good looks' that in 1926 he was approached by motion picture studios seeking a replacement for Rudolph Valentino, who had recently died. Though he declined the offer, there is no doubt that his extraordinary facial resemblance to the great screen idol played an important part in his appeal: the face of a Latin lover surmounting the body of an Adonis. It is hardly surprising that he has remained an 'icon' of gay culture, his photos - including some of the original (un-retouched) nude poses - still appearing today in gay books and magazines. In this respect, Sansone marked an important new development in twentieth-century male iconography. Both before and after him, attractive facial features have been seen as at most incidental to success in the world of men's bodybuilding: it is above all the body that counts. What Sansone incarnated was not the 'heroic' bodybuilding convention but the alternative 'erotic/aesthetic' convention - that in which the subject or representation is chosen for his capacity to elicit desire as much as (or more than) admiration. A male bodybuilder may rise to the top of his profession regardless of the handsomeness or otherwise of his features; for the male stripper or centerfold, on the other hand, they are as integral as his muscularity to the role he plays.

Finally, Sansone's importance can be linked with his popularizing of a more lither and athletic male physique than that displayed by Sandow and his other bodybuilder-strongman predecessors. Indeed, he owes as much to the dancer as to the weightlifter. It is significant that Townsend had been a theatrical photographer before turning to physique photography, having photographed the legendary Anna Pavlova and the modern dance pioneer Ruth St. Denis. Photographs of Isadora Duncan had also been influential in studio photography and had often conditioned the choice of poses. As Peter Weiermair has pointed out in relation to 1920s photography

From bookfinder.com

"The ideal of a man changed to the physically fit, muscular body so that dancers and athletes became favorite models. The shot was meticulously produced in a studio, so that the evolving sculptural effect could be gained through lighting. According to the social norms, dancers and athletes were allowed to appear as nudes . . . The combination of a powerful, self-confident body and a reminiscence of the Greek world creates a surreal mode of reality and ideal."

There can be little doubt that the dancing of Nijinsky, which has already inspired a remarkable study by Rodin, was an influential factor in Townsend's posing of Sansone. Nijinsky's celebrated performance as the Faun in the ballet L'Apres-midi d'un faune (which the dancer had himself choreographed to the music of Debussy) had not only caused a furor on account of its 'indecency' but, more significantly, had opened up to the European imagination a new perception of the expressivity of form and gesture of which the male body was capable. One need only compare the photographs of Nijinsky as he appeared in this role with a number of those taken of Sansone by Townsend to observe the striking resemblance of attitude. Having worked as a professional dancer, Sansone would undoubtedly have been familiar with the poses even if he had never seen Nijinsky perform in person.

In addition to the figure of the hero, the faun had been one of the leading motifs of ancient statuary, the Greeks identifying him with (or as an attendant on) the god Pan. Whilst some antique representations depict the faun figure as bestial - half man and half goat - others show him instead as a lithe and vigorous rural youth, either dancing or in a state of repose. His depiction provided the opportunity for a more sensuous portrayal of the muscular figure than that afforded by the noble or heroic gods, especially when not dancing he is often shown in a languid recumbent posture. When shown standing upright, the sway of his hips is overtly, almost provocatively sexual in suggestion (a theme also hinted at in Donatello's adolescent David), and when reclining he appears to be asleep, offering his inconscient body for the viewer's inspection. The potent sexual overtones of these bodily attributes were certainly not lost on Townsend. Nor were the darkly Italian features of his model. American fascination with an exotic, sensual Italy having reached a peak during the photographer's boyhood through the popularity of Nathanial Hawthorne's novel The Marble Faun.

All of the above factors combined to make Sansone most important figure since Eugen Sandow in the history of the developed male body. If Sandow was a Hercules of chiselled white marble, Sansone was a seductive and swarthy Pan. The first was the progenitor of bodybuilding; the second became the prototype of the male pinup.

Next: Sportsmen and Stars. The Progression of Bodybuilding.

No comments:

Post a Comment