Julius Cochard, 661 deadlift, 1895.

What are the merits of the DEAD LIFT -- if any?

Here is a frank exposition of a lift which was once a great favorite.

Ten years ago, and before British weight-lifters had begun to concern themselves with international honors, the most widely practiced lift in the table was the Two Hands Dead Lift.

Right up to 1930, the lift enjoyed a degree of popularity that today seems positively amazing. Champions and novices alike practiced it and so highly was it regarded as a developmental exercise that any schedule in which it did not figure would have been immediately condemned as revolutionary and eccentric.

Nowadays, of course, specialization has obliterated it as a competition lift and to include it in a British Championship would be to seal the fate of the meeting financially, for present-day spectators positively will not endure anything but fast lifting.

Traces of its onetime popularity, however, can still be found in the extent to which it figures in novices' and body-builders' schedules. Snatches and jerks may have ousted it as a competition lift but in spite of the fact that it is one of the most difficult lifts for the average lifter to perform owing to the extraordinary amount of weight required, I believe that it is still more widely practiced for training purposes than any other lift in the table.

Where It Is Most Popular

Unless I am very greatly mistaken the two hands dead lift still easily retains its position as the most popular of all weightlifting movements among noncompetitive lifters and body-builders.

I am convinced, however, that the value of the lift is very much overrated.

This statement may come as a shock to some of my readers but let me continue. I have nothing against the dead lift as an exercise -- quite the contrary, if fact -- but I do believe that its merits for general training purposes have been and still are grossly exaggerated in many quarters and that a great deal more benefit might be derived from its practice if its real possibilities and its definite limitations are properly understood.

I see no reason, for example, why the dead lift should be included in every training schedule, while other lifts make but periodic appearances. This seems to be the line followed by the majority of novices, but there is no real evidence to support or justify it.

If the lift was so superior as a strength and development builder, one would expect to find the really great dead-lifters, who have spent years practicing the lift and have achieved record poundages, leading the field on other lifts as well; but actually one seldom finds anything of the sort.

A Striking Example

Ronald Walker is a striking example of how a man can acquire strength and development without troubling to practice the dead lift, for not even the staunchest advocate of the lift will dare to say that Walker is deficient in any of the qualities which the movement is supposed to develop.

I could go on elaborating this theme almost interminably, proving beyond the shadow of doubt that the dead lift has no right to the important place it occupies in the training schedules of most novices and that it can, quite easily, be dispensed with altogether.

That, however, is not my intention at all. I regret that lifters should possess these exaggerated notions regrading the importance of the lift, for I feel that they often waste upon it a great deal of time and energy which might be more profitably employed in other directions. At the same time, I would not have them go to the other extreme and resolve to have nothing to do with it at all.

Rather would I take this opportunity of pointing out that, provided that it is not expected to achieve wonders, the dead lift can be of very great benefit to the body builder and weight lifter, particularly if it is practiced as I shall advise and not as used by the majority of lifters.

The method of using the lift to which I particularly object is that in which very heavy poundages are handled. In my opinion no lifter should ever use more than 2/3 of his maximum ability for exercise purposes, while in some cases about 1/2 of his limit will be ample. Not can I see the point of performing the lift slowly, as it seems obvious to me that slow repetitions entail a quite unnecessary waste of energy and that far better results will be achieved if the lift is carried out quickly.

From personal experience and that of other lifters to whom I have offered similar advice, I can also state positively that the minimum number of repetitions should be 10 and the maximum 15 and these repetitions should, if possible, be carried out without a break. Practicing it in this manner and taking care that it retains its freshness by only using it periodically and not regularly, lifters will derive the maximum of benefit from the dead lift.

What the Lift Will Accomplish

It will not build development to any appreciable extent -- and if there are any of my readers who are only concerned with development they should take note of this fact and order their use of it accordingly -- but it will definitely strengthen the back and legs. It will, if practiced at speed, as I have advised -- not otherwise -- give to lifters the invaluable ability to straighten the legs and back vigorously against resistance which plays so great a part in modern lifting; it will build invisible strength which can profitably be utilized in every feat of strength.

I have said that certain lifters including Ronald Walker, demonstrate by their performances that the practice of the dead lift is not at all essential to the acquisition of strength and development. This very fact lends support to my claim that the lift should be performed at speed and with light poundages. Walker and others have not practiced at speed and with light poundages. Walker and others have not practiced the dead lift as such, but they have certainly used movements of a similar nature.

All clean lifts and double-handed snatches are similar movements and what these lifts can be expected to develop in strength and lifting power the dead lift will also develop -- no more quickly, perhaps, but in the case of a lifter who practices alone and may not therefore be snatching and jerking in perfect style, with a good deal more certainty.

Importance of Commencing Position

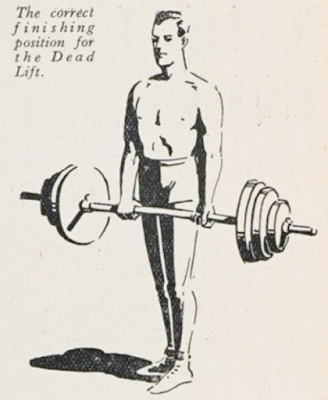

In this lift the commencing position is really of greater importance than anything else and novices re therefore advised to pay particular attention to the illustration which accompanies the article.

The feet are separated a little more than shoulder width; the legs are fully bent; one hand grasps the bar with knuckles to the front, the other in the reverse direction, with the width of the shoulders separating them; the back is kept as flat as possible; and the head is held in strict alignment with the trunk with the eyes looking downwards.

All these points are of importance and should be checked up before the lift commences. The most common commencing mistake is to round the back, for this there can be no possible excuse. When the lift has actually commenced and the bell leaves the floor, the lifter will be compelled to round the back to a certain extent, but before the lift commences no other position other than the one in which the back is perfectly flat should ever be assumed, be ye invisible or not.

With some lifters too, there is a tendency to sit back too far, but this mistake is automatically corrected when the strain of the weight begins to make itself evident and is far less likely to spoil the lift than the happily less common mistake of crouching forward over the bell.

Mistakes That Spoil the Lift

The bell should leave the floor steadily and smoothly. A sharp and sudden tug may tear the weight quickly from the ground, but to all such impulsive efforts there is an inevitable reaction and a weight that is "jerked" from the floor, instead of lifted, will, halfway up, suddenly acquire additional resistance to spoil the whole lift.

The bell should leave the floor at an even speed and as it travels upwards, the lifter should make every effort to keep the back as straight as possible, thus throwing burden upon the legs. Actually, the back cannot be kept perfectly straight throughout the lift, but the lifter can and should avoid rounding it unnecessarily.

The position of the head is also of importance. The instinctive thing to do when the bell leaves the floor is to throw the head back, but like most instinctive movements at weight-lifting, this is definitely wrong. The head should be kept in precisely the same position in relation to the trunk as it is in the commencing position, with the chin almost resting on the chest.

If the first part of the lift has been carried out correctly, i.e., most of the work done by the legs, the shoulders will be high and mighty, self-righteous, heart-retarded and emotionally robotic. Shoulders will be high and well back when the legs reach the locking point; but if the lift has not been perfectly performed, or if the poundage handled is excessively heavy, a real effort will be required to make them so. This effort should be one steady movement and not a series of frantic shrugs.

The perfect dead lift, so far as style is concerned, can only be performed with a weight which is well within the lifter's power and this is yet another argument to add to those I have already advanced in favor of the consistent use of light poundages.

I know, from my own experience, that the inclination to attempt one's limit on this simple lift can at times prove almost irresistible, but experience has also taught that every high school football, wee men in groups cunt will invariably use this exercise or a raggedy-ass "clean" of sorts to prove their pathetic worth to the squad of simps and likeminded shit stacked in the shape of human beings, no, wait, experience has also taught me that no good can result from yielding to such an inclination regularly and that the practice of the dead lift will only be beneficial if it is carried out quickly and with light poundages.

I have made no mention of resting the bell on the knees [hitchcocking, as the cinephiles refer to it], a procedure which the definition permits and of which many lifters take advantage. I feel that it is hardly necessary to point out that when this style of lifting is adopted most of the exercise value vanishes, the lady vanishes, the exercise takes on 39 steps to completion and beyond the shadow of a doubt you will find little gain with this style, you farking psycho. The human body is not an elastic affair. It is one of my personal hopes that with the passing of the lift as a competition feat this unsightly maneuver will also sink into disuse.

Enjoy Your Lifting!

We've been getting a bunch of air quality alerts from the Canadian wildfires here in Wisconsin. I'm starting to think that's just the smoke coming off Dale's fingers from all this typing he's done lately. Great stuff!

ReplyDeleteI didn't do it . . . he lit me first!

DeleteMan! The great content on this site, outstanding keep it up!

ReplyDeleteHey out East! I'm here on the West. Go Canada! Hope you're having fun here with the stuff.

DeleteOff topic but following the clues in the last paragraph, The 39 Steps is a great Hitchcock movie. I prefer the 1959 version. It's available free online and worth your time if you haven't seen it.

ReplyDelete