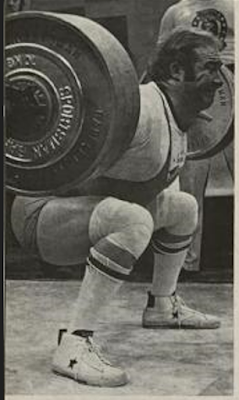

John Davis, shown performing a full squat with 530 pounds.

From practically the beginning of the sport of weightlifting, the "squat" or "deep knee-bend" with a weight on the shoulders has been recognized as a valuable exercise for strengthening the muscles that straighten the legs.

Once it was discovered that more weight could be raised to the shoulders, or to arms' length overhead, by "dipping" under the rising weight and straightening the body up by leg strength, naturally the knee-bend became a popular exercise for increasing the lifter's leg power. And it may be presumed that it was not long after this that certain lifters found the squat, or deep knee-bend, to come "easy" to them and so were stimulated into setting records in this exercise, thus changing it into a competitive lift also.

Away back in 1896, Max Danthage, a middleweight lifter of Vienna, did the knee-bend 50 times in succession with 100 kilos on his shoulders. He also set a then-record by doing the same movement with weights no fewer than 6,000 times consecutively in three hours.

Again, in 1899, a German heavyweight lifter named Herman Sell did seven consecutive squats with 200 kilos on his shoulders.

But there are a considerable number of ways of lowering and raising the body by leg strength in addition to the basic movement of doing so with a barbell or other weight across the shoulders. And as some performers may excel in one variation of this exercise, or lift, and some in another, it should be of interest to analyze the possibilities of the knee-bend (so far as the amount of extra weight liftable is concerned) in its several variations.

If, of two men of the same bodyweight, one is able to do a deep knee-bend with a 100-pound barbell on his shoulder and the other with a 200-pound barbell, it would be natural on first thought to conclude that one man was just twice as strong (in the muscles involved" as the other. But on further thought it will be realized that each man has to lift the weight of his own body (from the hips up) as well as the additional weight on his shoulders, and that accordingly in appraising the respective performances of the two men the weight of each man's upper body will have to be estimated and added to the weight of the barbell lifted.

If each man weighs, say, 170 pounds and is well proportioned muscularly, the weight of his upper body will be about 90 pounds. Accordingly, the first man, in having done a knee-bend with 100 pounds, will actually have lifted (including his upper body weight) about 190 pounds, whereas the second man will similarly lifted about 290 pounds.

Thus, the second man will really be only 290/190, or 1.526 times as strong, rather than twice as strong, in leg extensor muscles as the first man.

Now, bearing the foregoing illustration in mind, let us analyze from the standpoint of body mechanics a number of ways of squatting or deep knee-bending in various positions, both with and without extra weight being carried, with the view of determining the relative amounts of leg strength required in the different positions.

To start with, let us assume that the lifter performing these various lifts or exercises is 68 inches in height, is symmetrically proportioned throughout (both skeletally and muscularly), and weighs 170 pounds. The weight of the upper part of his body (or that portion of the muscles being used in straightening the hips, knee and ankle joints) in such a man will weight (as in each of the men in our first example) about 53 percent of the total bodyweight, or about 90 pounds.

In the following examples it will be assumed, further, that the respective lengths of the segments of the body (trunk, thighs, and lower legs) involved in the mechanical computations are typical for those of a man 68 inches in stature or standing height.

These lengths, so far as practical considerations go, are about as follows:

1) from the level of the resting position of the barbell on the shoulders to the center (in mid-plane) of the hip joints,, 22 inches;

2) from the hip joints to the knee joints, 18 inches; and

3) from the knee joints to the ankle joints, 15 inches.

The foot length, weighted, of our subject will be about 10.5 inches; but it should be remembered that not all this length will be subject to leverage, since the lever-arm will be mainly from the ball of the foot to the ankle joint; also, the feet will be pointed somewhat outward, rather than straight fore-and-aft, although this will not shorten the length of the lever-arm from ankle joint to ball of foot.

As a matter of interest, let us assume, finally, that our imaginary 68-inch, 170-pound weight-lifter is of maximum strength for his size, and can do an ordinary, flat-footed squat while holding a 500-pound barbell on his shoulders. The "mechanics" of this lift are shown in Figure 1, which depicts the lifter at the stage where his thighs are horizontal an the maximum leverage is being thrown on the leg muscles.

To simplify matters, I have considered only the stresses put on the knee joints and the hip joints, and have ignored the back muscles and those of the lower legs and feet. In some cases, it is true, a lifter may fail to rise in a flat-footed squat on account of his lower back muscles being weaker proportionately than his leg muscles (or on account of his lumbar spine being too limber and tending to arch unduly. I was of this type, and could squat with more weight on my toes than flat-footed!). However, such cases are rare, and success in rising with a heavy weight in the squat is nearly always primarily dependent on the strength of the muscles here being considered, namely the extensors of the knees and of the hips.

In Figure 1, it will be noted that when the thighs reach a horizontal position (the stage of maximum leverage on the knee and hip extensor muscles), the stress of rising with a 500-pound barbell plus the weight (90 pounds) of the upper body in a 170-pound man produces a leverage on the two knee joints equal to 1,416 pounds and on the two hip joints to 1,628 pounds. This is proceeding on the assumption that the distance from the center of the knee-cap to the center of the area where the thigh quadriceps attaches to the upper front of the tibia is 2.5 inches, and that similarly the distance from the center of the hip joint to the center of the area where the gluteus maximum muscle attaches to the upper back of the femur is 4.3 inches.

While these figures can only be approximate, they will suffice for our comparative study, since they will remain the same in the differing body positions used in various styles of knee-bending.

Finally, the drawings show the thighs as being somewhat shorter in relation to the lower legs than the measurements given above indicate. This is because of the outward turning of the feet (and the thighs) necessitated in assuming a strong, natural position in squatting. When the heels are raised from the floor, the performed can, of course, point his thighs directly fore-and-aft if he desires; but the usual position for sinking into a flat-footed squat is one in which the toes are turned outwards to about 45 degrees.

Now, having noted in Figure 1 the respective stresses thrown on the muscles of the front thighs and the buttocks, let us consider the so-called "Hacke" lift, in which the barbell is held behind the hips while a knee-bend is made on the toes. Incidentally, to avoid confusion, it is well to use the term "squat" in referring to a flat-footed deep knee-bend, and the term "knee-bend" is one where the heels are raised as the body is lowered.

Referring to Figure 2, it will seem that in the "Hacke" lift our 170-pound strong-man can raise only 187 pounds as compared with 500 pounds in the squat. A study of the respective leverages put on the knees in the two styles will show why this is so . . .

With a barbell on the shoulders, the center of gravity falls only 6.5 inches behind the knee joints; whereas with the barbell held in the hands behind the hips, the center of gravity is nearly 14 inches behind the knee joints. If we assume that the ration o these two distances determines the total amount of weight (that is, of the barbell plus the weight of the upper body) liftable, then for a 170-pound man to lift 187 pounds in the "Hacke" lift is equivalent to lifting 500 pounds in the squat.

Under this assumption, the stress on the knee extensor muscles is the same (1,534 pounds) in both lifts; but whereas in the squat the stress on the hip joints (or the gluteus maximus muscles) is 1,698 pounds, in the "Hacke" lift it is only 208 pounds.

Moreover, in the "Hacke" lift there is obviously a much greater stress on the muscles of the lower legs and soles of the feet than in the squat, although in the accompanying diagrams I have not attempted to take these stresses into account.

It would appear, however, that the squat is a better exercise for developing the gluteal muscles, and the "Hacke" lift (or the knee-bend on toes) perhaps a better exercise for the front thighs and the calves.

Space does not permit showing diagrams for all the variations of squatting and knee-bending that are possible. However, if the reader will bear in mind that if he is fairly symmetrically proportioned the weight of his upper body is approximately 53 percent of his total bodyweight, he should be able to figure out his probable abilities in the various squats and deep-knee bends by adding the weight of his upper body to the weight of the barbell lifted.

By this means, for example, it is easy to see that if a 200-pound lifter does a squat on one leg, he raises with the active leg the weight of his upper body, 106 pounds) plus that of his inactive leg (47 pounds), or a total of 153 pounds with one leg.

Now, to put the same stress on both legs, manifestly the lifter would have to raise 153 x 2, or 306 pounds. But since 106 pounds of this would be supplied in the weight of his upper body, the additional weight of his upper body, the additional weight (of the barbell carried) would have to be only 200 pounds. Thus, to squat on one leg is equivalent to squatting on both legs with a barbell on the shoulders weighing the same as the lifter weighs.

Away back in 1907, the famous French professional strong-man, Jean Francois le Breton . . .

. . . who weighed an even 200 pounds, did a deep knee-bend (on toes) with a 386-pound barbell on his shoulders. He also did a squat on one leg while holding a 181-pound barbell at his chest. These feats demonstrated considerable leg strength, since they were equivalent to a two-leg squat with 562 pounds. But le Breton had a tremendous pair of thighs, and was known to excel at all forms of back and leg strength.

Gabriel Lassartesse . . .

. . . a French strong-man and wrestler of about the same period, who weighed 174 pounds, was noted for his exceptional thigh development. He performed 5 consecutive deep knee-bends on his toes while supporting on his shoulders a 298-pound barbell. This was equivalent to squatting with about 385 pounds once, which would be a tremendous feat for a 174-pound man.

Clarence Weber . . .

. . . the old-time all-round champion strength athlete of Australia, did a one-leg squat with 160 pounds 3 times in succession, which was equal to doing 170 pounds once. Weber weighed 200 pounds; hence his one-leg squat was equivalent to squatting on both legs with 540 pounds. Weber had a splendid all-round physique, but his leg development was really outstanding.

When Henry "Milo" Steinborn . . .

. . . first came to this country, in 1921, he performed various sensational feats of strength, especially two-leg squats with 500 or more pounds on his shoulders. But perhaps the GREATEST of his leg feats, and one seldom mentioned, was a one-leg squat with 192 pounds at his chest. As Steinborn weighed 210 pounds at the time, and accordingly weighed about 110 pounds in his upper body, this one-leg squat with 192 pounds was equivalent to a two-leg squat with 192 + 110 + 50 (the latter being the weight of one leg) x 2 - 110, or 594 pounds!

And as Steinborn is reputed to have done on at least one occasion 5 consecutive squats with 550 pounds, a single effort with 594 is credible. This feat has been surpassed only, so far as I know, by that of the English strongman-wrestler, Bert Assirati . . .

. . . who some years ago squatted with 550 pounds 10 times in succession while weighing 260. He also did a one-leg squat with 200 pounds, which was equal to a two-leg squat with 638 pounds!

It would be interesting if some of the present-day champs, such as John Davis, Stan Stanczyk, Pete George, and some of the leading body-builders would report what they can do in a one-leg squat. Can they surpass the best efforts of old-time strong-men in this test of leg strength?

Enjoy Your Lifting!

Another interesting variation from the early days of Physical Culture is the the Deep Knee Bend on Toes with the bar on the shoulders. Bob Hoffman is demonstrating in your earlier blogpost:

ReplyDeletehttps://ditillo2.blogspot.com/2023/10/the-deep-knee-bend-bob-hoffman-1948.html

Without weight, it requires both balance and strength. With additional weight, it becomes an impressive feat of co-ordination and strength.