Most people work out in gyms where the population consists of recreational trainees and a handful of bodybuilders. Generally speaking, there are no track and field athletes, collegiate or pro football players or Olympic weightlifters, as these people tend to train in team or college weight rooms. Other athletes go where the strength coaches and facilities are, and that is not in the popular gyms.

Hence, few recreational trainees are exposed to strength training, and most assume that no one trains that way. This is a very narrow point of view.

There are, in fact, several types of progressive-resistance training. The typical recreational weight trainee performs what comes under the heading of bodybuilding workouts. These include exercises that work all the different bodyparts and are geared toward overall conditioning and total-body development.

In addition to bodybuilding, however, there are two sports in which athletes train for maximum weight on specific lifts: Olympic weightlifting, which involves the clean & jerk and the snatch, and powrlifting, which involves the squat, the bench press and the deadlift.

One exercise that comes from Olympic lifting and carries over to nearly all sports is the power clean. Although it is a mainstay for many athletes in weight rooms around the world, this movement is, unfortunately, rarely seen in bodybuilding gyms.

What exactly is a power clean?

If you've ever watched Olympic weightlifting on television, you've probably seen the event known as the clean & jerk. The clean is the action of pulling the bar off the floor and dropping your body into a full front squat position of a front squat with the bar racked across the front of your shoulders. This is also known as a squat clean or full clean.

In a power clean you don't drop as low as a full squat; you only go down to a half-squat position or higher. This is an exercise that you must perform with good technique and, as you become accustomed to it, quick movements.

The muscles that provide the action for the clean include the quadriceps, hamstrings, glutes, erector spinae and trapezius, as well as stabilizers like the abdominals, the gripping muscles of the hand and forearm and the calf muscles when you rise up on your toes. The only exercise that comes close to utilizing this many muscles is the squat.

In performing a power clean, you pull the bar very close to your body as you pull it up, and you must actually move around the bar in order to get under it. By keeping the bar close to your body, you keep the levers short, which enables you to lift more weight and reduces your chance of injury.

Research studies performed in the late 1970s identified several factors that made the difference between world- and national-class weightlifters. It seems that the national-class lifters usually lower themselves under the bar at a speed that's 15% slower than gravity, while world-class lifters get under the bar at a speed that's 8% faster than gravity.

This means that world-class lifters actively pull themselves down under the bar, and national-class lifters slow themselves down while assumit the full front-squat position. The slower movement requires the national-class athletes to pull the bar significantly higher, as much as six inches, in order to have enough time to get under it. The world-class athletes, on the other hand, are quick enough to get under the bar, and since they don't have to pull it as high, they can lift more weight.

As you can see, the clean is a very complex movement - more complex than many give it credit for.

In addition to the above-described distinctions, there are a number of different pulls that were developed around the time these studies were done. The double pull and the Bulgarian pull provided ways to re-recruit the quads during the pull and reduce the torque and levers in and around the low back and hips; however, we'll save discussions of those for another column.

I asked Mike Reed, D.C., of Grover City, California for his input on the power clean. Reed has been the team physician for the U.S. Olympic weightlifting team since 1989 and is a certified strength and conditioning specialist.

"Without a doubt the power clean is the best all-around exercise," he said. "Mike Stone (a Ph.D. at Appalachian State University in Boone, North Carolina) did research that has shown that it burns more calories than any other exercise and that it has a residual carryover of an increased metabolic effect. This is perfect for bodybuilders who are cutting up. They don't have to use it for size gaining even though their erectors and traps will thicken and the phenomenal stabilizing by their abs will help bring them out too."

Bodybuilders who include power cleans in their training should be careful how they work them into their routines, however. Like the deadlift, the power clean doesn't lend itself to high reps; in fact, high rep deadlifts and cleans frequently lead to low-back fatigue and injuries.

"I advise bodybuilders to do 5 to 6 sets of certainly no more than 5 to 6 reps," Reed said.

In addition, the movement may take some getting used to. "Some powerlifters and bodybuilders who are not used to the clean find that they don't have the wrist flexibility that is needed," Reed continued. "In these cases I tell the athlete to focus on the pull and the shrugging motion at the top of the clean and not to worry about racking the weight (across the shoulders)."

This motion is called a "pull," or in this case a "clean pull," in which the clean is performed exactly as you normally would except that you don't rack the bar. This requires the use of rubber bumper plates, and they are usually performed on a lifting platform.

It also requires a cooperative gym owner. Performing high-clean pulls and dropping the weight does not go over well in many gyms.

The technique involved in the Olympic lifts is generally very complicated. While the power clean is a little less complex, it would be a fabrication to tell you that you could learn how to clean from a few pictures and the space limitations of a column like this, but here's a general description.

Start with the bar resting against your lower shins.

Grip the bar with your hands at a comfortable distance that's slightly wider than your shoulders.

Bend you knees and maintain your back in a flat or slightly arched position, but not rounded.

As you begin to stand, quickly pull the bar, keeping your back flat and your elbows straight.

Don't pull with your arms - THIS IS NOT A CHEATING UPRIGHT ROW.

As you elevate the bar, incorporate a powerful shrugging motion, still keeping your elbows straight.

At the same time rise up on your toes as if you were performing a calf raise.

Then do a high pull, the movement during which you actually pull yourself under the bar.

These combined efforts significantly speed up the movement of the bar and recruit all the major muscle groups, in addition to providing the elevation of the bar that you were looking for.

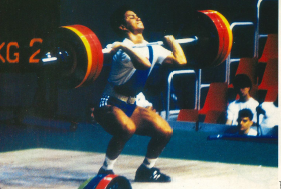

With that accomplished, drop your body into a half-squat position, which should place you under the bar, as in the photo:

Then stand up straight with the bar across your shoulders.

This is a power clean.

"While the power clean is one of the best all-around movements, it is also one of the most dangerous," Reed warned. He was talking about the torque that's placed on the back when you perform a clean with poor technique; for example, pulling the bar too far away from your body, which can cause an injury. Over-training on this movement can also lead to low-back injury.

Proper power clean technique is something that you can carry over to your everyday life in terms of lifting things correctly. "I teach my low-back patients and even post-surgical patients the proper lifting techniques for the clean," Reed continued. "For an average low-back patient we start with the stabilization of the torso. After we have achieved that, we teach the clean position, not the clean. This involves keeping the torso tight and stable and learning to keep the weight or object close to the body. Then we progress to a dowel or stick. Finally, we work up to an empty Olympic bar."

In the case of athletes who have suffered an injury, the elimination of low-back pain may not be enough. Athleted must learn to move and lift properly again. Many teams and schools require strength minimums, and athletes must perform a clean, a squat and a bench press up to certain standards before they can return to a starting or playing position. Learning proper technique is crucial to their careers.

"The 50th percentile in the clean for a collegiate linebacker is a 245-lb. clean," Reed explained. "We want to see the rehabilitated linebacker return to at least the 50th percentile."

The power clean is usually the talk of the football training camps. Several years ago defensive end Pete Koch of the Kansas City Chiefs broke the team record with a 350-lb, and by cleaning his bodyweight five times. Shot putter John Brenner told IRONMAN magazine that he spent a great deal of time with the clean and that he performed a power clean with 460 lb. [October '90 issue].

Of course, the Olympic weightlifters pull enormous poundages. For example, the 123-lb champion who performed a clean & jerk with triple his bodyweight. The super-heavyweight record is approximately 585 lb. These athletes all have powerful looking physiques, much of which is attributable to the power clean.

At this point we've barely scratched the surface of what there is to learn about the power clean. We'll address the lift in more detail in a future column.

No comments:

Post a Comment