The One-Arm Bench Press

by

John Christy

(2008)

In my 34 years under the iron, I'll be the first to attest that there is little that is truly new. Even if something seems to be new, it was either done long ago, or we simply haven't heard of it. So, when I say that what you'll learn in this piece is new, it is as such because I've never heard or seen it recommended before (although some very strong guy training in his garage in Cleveland or Budapest has probably done it).

The exercise I'm going to describe is one of the most difficult exercises I've ever performed. And as any experienced iron-guy will attest to, when something is very difficult to do - and you do it appropriately - expect strength and muscle gains in return.

The ironic thing is that I discovered this movement, and what I'm confident will become one of the best movements you're ever hated to perform, out of necessity. What's that saying . . . something about necessity, mothers, and invention.

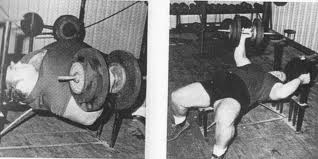

Several months ago I injured my right arm/shoulder getting a dumbbell into position to perform an incline DB bench press; a partial tear of the bicepital tendon. Well, I've never been one to just sit around and letting something heal while the rest of my body strength returns to my previous 118-pound high school sophomore level. So, I devised a way to continue to train my entire body without any damaging stress to my right arm; hands-free front squats with a special apparatus, one-arm pulldowns and T-bar rows, one-arm overhead presses, calf raises with a hip belt -- and the 'unsupported' one-arm dumbbell bench press -- to name a few. I say unsupported, because I couldn't use my right arm at all to stabilize myself. I couldn't hold onto the upright like this -

- couldn't hold a dumbbell in my right hand to counterbalance the weight in the left, heck, the injury was so bad I couldn't lift my right hand to brush my teeth (seriously). So, I was forced to just hold it - carefully - on my stomach while I pressed with my left arm. I just dug my feet in and flexed my core as hard as possible to stabilize myself and went at it.

This was extremely awkward at first, requiring great 'real' core strength, because I had to fight to gain and maintain stability. I had to use the strength of my entire body to counterbalance the weight I was using in my left hand; my hips, torso, and lower body were trying to twist me into a pretzel. They only way to 'keep my body straight' to avoid injury and to gain as much leverage as possible in the working arm (left), was to keep my body and especially my core flexed hard - very hard. And boy, you really need to keep your feet 'dug into' the floor.

I said this movement requires 'real' core strength because I'm talking about strength built through the use of heavy weights on basic exercises. I'm talking about 150-200 lb. strict situps, 120-160 lb. side bends, 80-100 lb. dumbbells (held at the collarbone) back extensions, and full range arched-back good mornings using over 300 lbs. - with all movements held in the contracted position for at least a full one-thousand-and-one count.

The awkwardness created by having no leverage is what makes this movement great for building the barbell bench press - especially the bottom part of the bench press. As any trainee who understands the conjugate methods popularized by Louis Simmons Westside Barbell Club - having 'no leverage' is what makes this movement extremely productive in building strength that carries over to helping the barbell bench press.

The Benefits

In order to maximize one's pressing ability the scapula must be retracted (pulled together)

and depressed (pulled downward) and held there throughout the lift. This not only allows the trainee to maximize the strength of the pressing muscles but it also prevents injuries to the shoulder by stabilizing what is called the glenohumeral joint. This requires great strength of the upper back musculature and most importantly, it is a skill that must be practiced to be mastered while using a heavy barbell. Well, the unsupported DB bench press takes this 'practice' to a new level. The upper back musculature has to learn to flex even harder than required with a barbell in order to stabilize the weight being held in only one hand. Without maintaining retraction - to the point of cramping the traps and lats - the trainee has no chance to get the dumbbell out of the bottom position with any appreciable weight.

- couldn't hold a dumbbell in my right hand to counterbalance the weight in the left, heck, the injury was so bad I couldn't lift my right hand to brush my teeth (seriously). So, I was forced to just hold it - carefully - on my stomach while I pressed with my left arm. I just dug my feet in and flexed my core as hard as possible to stabilize myself and went at it.

This was extremely awkward at first, requiring great 'real' core strength, because I had to fight to gain and maintain stability. I had to use the strength of my entire body to counterbalance the weight I was using in my left hand; my hips, torso, and lower body were trying to twist me into a pretzel. They only way to 'keep my body straight' to avoid injury and to gain as much leverage as possible in the working arm (left), was to keep my body and especially my core flexed hard - very hard. And boy, you really need to keep your feet 'dug into' the floor.

I said this movement requires 'real' core strength because I'm talking about strength built through the use of heavy weights on basic exercises. I'm talking about 150-200 lb. strict situps, 120-160 lb. side bends, 80-100 lb. dumbbells (held at the collarbone) back extensions, and full range arched-back good mornings using over 300 lbs. - with all movements held in the contracted position for at least a full one-thousand-and-one count.

The awkwardness created by having no leverage is what makes this movement great for building the barbell bench press - especially the bottom part of the bench press. As any trainee who understands the conjugate methods popularized by Louis Simmons Westside Barbell Club - having 'no leverage' is what makes this movement extremely productive in building strength that carries over to helping the barbell bench press.

The Benefits

In order to maximize one's pressing ability the scapula must be retracted (pulled together)

and depressed (pulled downward) and held there throughout the lift. This not only allows the trainee to maximize the strength of the pressing muscles but it also prevents injuries to the shoulder by stabilizing what is called the glenohumeral joint. This requires great strength of the upper back musculature and most importantly, it is a skill that must be practiced to be mastered while using a heavy barbell. Well, the unsupported DB bench press takes this 'practice' to a new level. The upper back musculature has to learn to flex even harder than required with a barbell in order to stabilize the weight being held in only one hand. Without maintaining retraction - to the point of cramping the traps and lats - the trainee has no chance to get the dumbbell out of the bottom position with any appreciable weight.

This movement will also teach (or should I say force) you to learn what I consider to be the ideal 45 degree angle of the upper arm (humerus) relative to the side of your torso. Some benchers keep the humerus at a much greater angle, some nearly 90 degrees - because they feel that they can use their pecs better in this position. Experience has taught me that this is not optimal because you can't retract and depress the scapula maximally with the humerus at this angle. Also, as the angle increases, tremendous unnecessary harmful forces are created on many structures in the shoulder - especially the pec tie-off. When trying to stabilize one arm you'll have to optimally retract and depress the scapula, and this will pull that arm closer (relative to a 90 degree angle) to the side.

And if you're a bencher who doesn't use the tricep to its maximum; meaning that you don't focus on flexing, or creating tension in the tricep when driving the bar out of the bottom position - this movement will teach you. As a matter of fact it will force you to learn to use your triceps.

Performance

I would suggest that you use dumbbell holders so that you can start the movement at the top position, and so that you can avoid having to put the DB on your leg and 'kick it' up into position (although this is what I did for years - until this last injury).

It really doesn't matter what you do with the non-working arm - just don't hold on to anything, including the pad on the bench. I had to rest mine on my stomach simply because it cause pain to put it anywhere else.

Before you begin the descent squeeze those shoulder blades together as if you're trying to cause a spasm in your upper back muscles. It'll feel odd at first to try to squeeze the non-working side without any weight in that hand, but stay with it. You will learn to do it.

As you lower the weight you'll not only have to keep your entire upper back tight, your pressing muscles on the working side tight, but you'll be forced to keep your entire body tight - especially all the muscles in your core, and you will definitely have to use your legs and dig your feet in like never before! Your body will try to 'twist' toward the working side as the DB reaches the lower position - DON'T LET IT - stand your ground and keep your shoulders and hips parallel with the ceiling. This takes tremendous concentration, and of course tremendous core strength. You'll find out very quickly how strong your middle is.

Now, to have a chance to get a heavy weight out of the bottom position, you'll need to keep your upper back in a near spasm. If you scapula 'pulls out' even a little - you're done - you won't make the lift. This exercise is very unforgiving; any flaws in technique or bodily tension and you will fail to make the lift.Learning to maintain maximum levels of tension in the muscles that stabilize the parts of the body that allow the prime movers to generate maximum strength is what makes this exercise so productive for building the barbell bench press. Your upper back musculature and the muscles of your midsection will think they are on vacation when you go back to pressing a barbell that has both of your hands holding it, and the weight counterbalanced perfectly between both sides of your upper body.

Place in the Schedule

Not very complicated here. Use the unsupported DB bench press as your stand-alone work for three to four months. Perform a set or two or 3 reps on the regular bench press with 80% of your one rep max once a week with the barbell as a warmup for the unsupported bench if you want to keep your groove with a bar.

If you follow any of he variations of the conjugate method, the unsupported DB bench makes a fantastic Maximal Effort (ME) movement. I would strongly suggest several weeks of using it as an auxiliary movement following your usual ME movement for several sets of 5 to 8 reps so you can develop the unique whole-body motor skills and strength necessary ot make this movement productive - and to avoid getting hurt by using too heavy a dumbbell too soon. Please take the 'getting hurt' part seriously. Take your time working up to heavy weights with this one.

Once you get the movement down and get your core strong enough, plug it right in as an ME movement. Simply work up using sets of 3 reps until you can not longer make the 3 reps and then perform singles until you arrive at or get close to your one rep max for the session. A great way to utilize this as an ME movement is to cycle it through a 4 to 6 week mesocycle using different angles of incline. For instance, I would suggest that you start with a regular flat bench. Establish your one rep max and the next week use a 30 degree incline. The following week use a 45 degree incline. The next week use a 60 degree incline. Then, over the next three weeks work your way back down, breaking your one rep maxes along the way.

Give it a try!

No comments:

Post a Comment