Table Training

Table Training program for learning the plate squat

Click Pics to ENLARGE

Figure 1

Figure 1.

Plate squat viewed from the side: top (a) and bottom (b).

Volleyball has been placed on top of the plate to encourage the athlete to use proper technique.

Figure 2

Figure 2.

Improper performance of the plate squat.

Figure 3

Figure 3.

Overhead squat: 45° view (a) and side view (b). The bar must remain in the optimal “window” (dashed lines in (b)) during the entire lift. If the bar moves out of this window, the lift should be terminated.

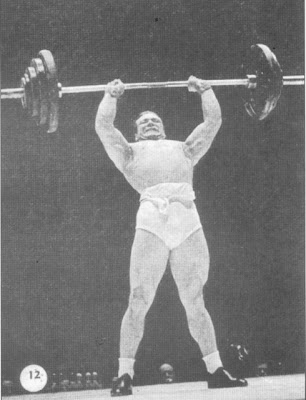

Figure 4

Figure 4.

No-arms front squat viewed from the side: top (a) and bottom (b).

Figure 5

Figure 5.

Front squat viewed 45° from the front: top (a) and bottom (b).

Figure 6

Figure 6.

Back squat viewed from the side. The bar must remain in the optimal “window” (dashed lines) during the entire lift. If the bar moves out of this window, the lift should be terminated.

A Teaching Progression for Squatting Exercises

by Loren Chiu and Eric Burkhardt (2011)

Strength and Conditioning Journal

The Published Journal of the NSCA:

http://journals.lww.com/nsca-scj/pages/default.aspxThe squat is one of the most common exercises used in strength and conditioning programs. Squatting exercises have been used in both athletic and nonathletic populations to increase thigh muscle mass, lower body strength, and lower body power. Squat performance is associated with vertical jump and sprint performance (32) and has been reported to contribute to success during power movements, such as the snatch and clean (3). Despite the popular use of squatting exercises, dissenting opinions exist on how they are properly performed (6). The authors have empirically observed, primarily in athletes, a large variation in not only squatting techniques but also what appears to be a suboptimal technique when considering basic biomechanical principles.

Proper execution of squatting motions is required for the performance of advanced resistance training exercises, such as the snatch and clean. The snatch and clean require individuals to raise a barbell from the floor to an overhead squat and a front squat positions, respectively. These lifts require certain segment and lifter kinematics that are generally uniform across elite athletes (13). Inability to perform the squatting motions will result in a missed lift and potential injury to the athlete or will require the athlete to use an improper technique, minimizing the training benefits. Performing squats properly is also required to place stimuli on the appropriate musculature. Subtle changes in the kinematics or kinetics of the squat can greatly influence the muscular demands (21,28).

Salem et al. (28) reported identical segment kinematics in the healthy and previously injured limbs of individuals who had anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Despite similar kinematics, the healthy limb used a strategy emphasizing the knee extensor musculature, whereas the injured limb used a strategy emphasizing the hip extensor musculature. This difference can only be accounted for by a forward shift in the center of pressure in the injured limb (15). Because center of pressure requires a force platform to measure, this bilateral difference may occur without the strength and conditioning coach being aware of it. Thus, it is of particular importance that a coach uses the right coaching cues when teaching individuals to squat (as well as other exercises). The use of an exercise progression is a method in which a coach can teach more complex exercises. A 4-stage exercise progression is detailed for teaching squatting exercise, using a novel variant developed by one of the authors.

STAGE 1: THE PLATE SQUAT

Empirically, a common observation in individuals performing the front or back squat is inappropriate lumbar lordosis. Either hyperlordosis or hypolordosis will influence the posture of the trunk and position of the barbell relative to the feet, which will affect the loading of bone and soft tissue. These observations may be the result of excessive forward trunk inclination, a technique that shifts the mechanical demand from the knee extensors to the hip and trunk extensors (2,7,14). The plate squat exercise restricts the amount of forward trunk inclination possible, thereby encouraging an upright torso posture, distributing the mechanical loading across the hip, knee, and ankle joints.

To perform the plate squat, a weight plate is placed with the outer surface on the top center of the head and the opposite end held in the hands (Figure 1a). Initially, a 10-kg plate is appropriate, and the use of a rubber bumper plate is preferred as the larger diameter (45 cm) allows the plate to be held comfortably. The individual takes a hip width stance and takes a deep breath before placing the plate on their head. Holding the deep breath, the squat is performed by flexing at the hip and knee and dorsiflexing at the ankle simultaneously. While performing the plate squat, the plate should be held parallel to the ground (Figure 1b). If the plate drops below parallel (Figure 2), it is indicative of excessive forward trunk inclination and/or spinal flexion (i.e., loss of lumbar lordosis or excessive thoracic kyphosis). To encourage proper bumper plate positioning, a ball can be balanced in the center-hole of the plate (Figure 1a and 1b).

Although the mechanics of the plate squat have not been studied in a laboratory, research on spine biomechanics provides a scientific rationale for the effectiveness of the plate squat. The ligamentous spine, consisting of intact intervertebral discs, facet joints, and ligaments can support up to 80 N (approximately 8 kg) without buckling (9). The addition of axial loads exceeding 80 N results in reflexive activation of the spinal musculature to generate stability (8). In the plate squat, the resistive load is directed axially through the cervical, thoracic, and lumbar spine in the starting position, as opposed to the front squat and back squat where the resistive load is only directed through the thoracic and lumbar spine. However, it should be noted that this exercise may be contraindicated for individuals with cervical spine pain or injury. Individuals with cervical spine pain or injury should consult their physician before performing this exercise.

As the plate squat restricts motion of the trunk, it allows flexibility or strength limitations to be observed. For example, if the neutral spinal posture cannot be maintained with the 10-kg or 15-kg resistance, this suggests that the trunk stabilizing musculature is weak. Hypolordosis would indicate weakness of the erector spinae, whereas hyperlordosis would indicate weakness of the internal and external obliques and rectus abdominis (8,22). When the plate squat is properly performed, the torso should be upright in the deep squat position, the legs rotated anteriorly with the knee in front of the toes, and the weight distributed across the forefoot and rearfoot. In the authors' experience, athletes often learn the technique and demonstrate consistent performance after just a few repetitions. After a few sessions, the individual should be able to progress to a 15-kg plate and in a few weeks, to a 20-kg or 25-kg plate (Table).

STAGE 2: THE OVERHEAD SQUAT

The next exercise to appear in the squatting progression is the overhead squat, which also requires an upright torso posture. Like the plate squat, the nature of the exercise eliminates the possibility of excessive thoracic kyphosis and encourages the proper lumbar spine position. As implied by its name, the lift is performed by holding a barbell overhead with arms extended using the same grip width used for the snatch. Some athletes may be discouraged from performing this exercise because of flexibility concerns. However, it has been the authors' experience that the flexibility needed to properly perform this lift can be developed simply by practicing it. For example, if flexibility issues prevent an athlete from performing the movement through the full range of motion, a partial range of motion can be used. Over time, the trainee can slowly work on gradually increasing their range of motion with each session until the full range of motion is achieved. For many athletes, this strategy may be all that is needed, thus eliminating the need to perform special stretching exercises. It should also be noted that the appearance of poor flexibility may be related to motor learning, which explains how an athlete can make large improvements in the range of motion in a short period (i.e., between the first and second sessions). Although complex in appearance, the overhead squat can be learned rather quickly and with minimal instruction. If a trainee is able to maintain flat feet, proper knee position (thighs aligned with the feet) while holding the barbell in the correct position overhead (Figure 3), optimal technique usually follows. When viewed from the side, the barbell should be directly above the glenohumeral joint so that the humerus is essentially perpendicular to the ground.

The overhead squat is an excellent choice in the learning progression. It is much easier to teach and learn than its outward appearance suggests. In a manner of speaking, it can be described as “self-correcting” because it is difficult to perform incorrectly as long as the feet remain flat with the knees and barbell properly positioned. Overhead squatting develops and maintains the important qualities of ankle, hip, and spine and shoulder complex flexibility, while strengthening the lower extremity and stabilizing musculature of the shoulder complex and spine. The snatch balance (also known as a drop snatch), a more dynamic and “athletically appealing” version of the overhead squat, can be taught once the overhead squat is mastered. The snatch balance begins like the back squat with the exception of the snatch-grip hand spacing. To initiate, the lifter bends slightly at the knees (eccentrically controlled knee flexion) then explosively extends, “throwing” the barbell to arm's length while simultaneously moving into the bottom position of the overhead squat. In the snatch balance, the lifter moves into the squat position rapidly by 1) pushing themselves under the barbell and 2) rapidly jumping under the barbell using the flexor muscles of the lower extremity.

STAGE 3: THE FRONT SQUAT

Similar to the plate squat and overhead squat, the front squat requires the trunk to be maintained in an upright position. With substantial loading, excessive forward inclination of the trunk will result in the barbell rolling forward and off of the shoulders. Once the plate squat and overhead squat have been learned, the front squat can be introduced because it allows greater weights to be lifted. In the front squat, the barbell is held above and posterior to the clavicles, with the barbell pressed against the throat. To teach proper positioning of the barbell, the “no-arms” front squat can be used, where the hands are held in front of the torso (Figure 4a). As the individual squats down, the arms should be elevated to prevent the barbell from rolling off the shoulders (Figure 4b).

The hands should be positioned on the barbell using a “clean grip” (Figure 5a). The grip should be identical to the grip used when receiving the barbell in a clean or power clean. However, it is important to note that the grip should be relaxed, with the barbell resting on the shoulders. For some individuals, the hands may be opened up with the barbell sitting on the fingertips. ALTHOUGH IT IS COMMONLY BELIEVED THAT WRIST HYPEREXTENSION IS REQUIRED TO HOLD THE BARBELL USING THE "CLEAN GRIP," WRIST RANGE OF MOTION IS NOT USUALLY THE LIMITATION. RATHER, THE GLENOHUMERAL JOINTS NEED TO BE EXTERNALLY ROTATED, AND TIGHT INTERNAL ROTATORS (PECTORALIS MAJOR, LATISSIMUS DORSI, TERES MAJOR, AND SUBSCAPULARIS) MAY RESTRICT THIS MOVEMENT.

As the front squat is performed, the glenohumeral joint should further externally rotate, pushing the elbows upward (Figure 5b). This will ensure that the barbell remains on the shoulders. Additionally, this habit should be reinforced for athletes performing the clean. If the athlete catches the barbell in the clean with the elbows pointed down, they are more likely to contact the knee, which is a technical error, and may result in dislocation of the lunate or fracture of the bones forming the wrist joint (19,23,33).

On its own, the front squat is an effective exercise for developing dynamic strength in the lower extremity and postural stability in the trunk. Recent research suggests that there may be no greater leg strengthening benefit in performing the back squat over the front squat (18). However, the front squat can be performed with a lower absolute load, minimizing compressive forces on the spine and the tibiofemoral joints. From a practical standpoint, the front squat may be considered a safer exercise to perform, particularly when using rubber bumper plates. If an athlete cannot successfully complete the lift, they can simply push the barbell off their shoulders, allowing the barbell to drop onto the floor. Although the same can be done during a back squat, an athlete may attempt to “fight through” a repetition (whereas this is less possible with the front squat), losing spinal extension, which can result in serious injury if heavy loads are used.

STAGE 4: THE BACK SQUAT

The back squat is the final exercise taught in this progression. In the authors' opinion, the back squat should only be taught after the individual is capable of properly performing the front squat with substantial resistance. The use of the front squat will allow the individual to develop appropriate flexibility and strength to perform squatting movements correctly, as well as giving the athlete experience to decide when to “bail out” of a lift that cannot be completed safely. When the plate squat, overhead squat, and front squat can be properly performed, teaching the back squat becomes very simple. The individual only has to place the barbell across the back of their shoulders as opposed to the front of the shoulders. The squatting motion itself is the same as for the front squat, overhead squat, and plate squat (Figure 6).

One point to note is the position of the arms during the back squat. First, the hands should be gripping the barbell just outside the shoulders. In general, the narrowest grip possible should be used. Second, the grip should be relaxed, as opposed to hands firmly gripping the barbell. Finally, the elbows should be pointed down during the back squat, as opposed to backward. We have observed that allowing the elbows to point backward encourages forward trunk inclination, whereas pointing the elbows down encourages the trunk to remain upright.

THOUGHTS ON EQUIPMENT

The authors have observed that many coaches instruct squatting technique using a broomstick or PVC (polyvinyl chloride) pipe. In our experience, this makes it more difficult to learn squatting exercises because some resistance is needed to activate the appropriate musculature and encourage proper technique. Additionally, for individuals who are limited by their flexibility, the resistance will assist in lengthening the muscle-tendon unit. Following the progression, an individual who can perform plate squats with a 15-kg or 20-kg plate should be capable of performing overhead and front squats with a women's (15 kg) or men's (20 kg) bar.

Just as it is important to use proper technique when performing squats, it is recommended that these exercises be performed using the proper equipment. Front and back squats can be effectively performed using any suitable style of squat rack system or in the free/open space of a weightlifting platform (8' × 8' minimum) using a quality bar, bumper plates, and a portable free-standing squat rack or power rack located at one end of the platform. However, overhead squats should never be performed inside a power rack. Ideally, the overhead squat and snatch balance should be performed on a weightlifting platform using a bar with bumper plates because this setup accommodates a missed lift while reducing the risk of injury or damage to the equipment. Another benefit to performing squats on a weightlifting platform is that it designates a safe area where only the trainee is allowed.

It is recognized that not all facilities have sufficient space and equipment (bumper plates) to perform the overhead squat safely. This exercise should not be performed in such circumstances because safety will be compromised. Further, coaches who do not have experience performing or teaching overhead squats (and other weightlifting exercises) should seek help from experienced coaches. These exercises are taught in coaching education courses from weightlifting organizations, such as USA Weightlifting and the Canadian Weightlifting Federation.

MISSING A SQUAT

Beginning and experienced lifters alike will routinely experience missed repetitions when performing the overhead, front, and back squats. Although it may appear “shocking” to inexperienced coaches and trainees, dropping a bar loaded with bumper plates during a missed squat is a typical occurrence in weightlifting circles and learning to properly do so should be scheduled during the first session. Although most squat racks have built-in safety “catches,” the decision to “bail out” of a squat must be done quickly and the position of these safety “catches” may not allow an individual to miss a lift safely. The use of bumper plates and squatting outside of a rack will allow a lifter to miss a squat the instant proper technique is lost. If sufficient space and bumper plates are not available, squatting inside a rack and using spotters is recommended. However, in the authors' opinion, missing a lift by dropping a barbell loaded with bumper plates is also safer than having a spotter, which places 2 individuals in danger. It should be recognized that teaching athletes to miss a lift is an advanced coaching skill; therefore, it is recommended that inexperienced coaches learn the technique to miss a lift from an experienced coach.

Front squats are missed by losing the barbell in front of the lifter, whereas overhead squats may be lost in front or behind. To lose the barbell behind, the lifter simply has to jump forward quickly and may push the weight even further back to avoid being struck by the falling barbell. A missed lift in the front is even less intimidating as one needs only to quickly jump back while pushing the barbell forward.

The act of missing a heavy back squat may be the most dangerous situation in all of weight training if the lifter does not possess the knowledge and requisite skills. Although back squats are typically lost behind the lifter, the combination of poor skill (which can be avoided if the presented progression is followed) and torso weakness can lead to a lift lost in front of the body, presenting a very dangerous situation when attempting a heavy back squat. Add to this, the somewhat unusual location of the lifter, that is, between the barbell and the floor. This can give the inexperienced back squatter the feeling of being in a very precarious situation, especially because the decision to “bail out” must be made very quickly. With practice, missing a back squat in front of the body can be done by thrusting the barbell up and forward (similar to a push press). Beginning lifters should spend time practicing missing squats in front and behind their bodies until they are 100% confident that they can comfortably miss a heavy lift during a real-life situation.

THOUGHTS ON SQUATTING TECHNIQUE

Different coaches have expressed thoughts on a number of different aspects relating to squatting technique. In recent years, perhaps the most commonly discussed aspects are the stance width and whether to push the knees forward or the hips backward (16,20,26). These arguments are typically brought up in regard to the muscles trained and the amount of load lifted. As pertains to the amount of load lifted, the argument is proposed that using a technique that allows the most weight to be lifted will result in the greatest strength stimulus. However, this is a fallacious argument. If an individual performs a high-bar narrow stance back squat and then a low-bar wide stance back squat, they will typically lift more weight with the latter technique. However, they are not instantaneously stronger. The difference in weight lifted is because of changes in the leverage system (i.e., gaining a mechanical advantage) and possibly altering the muscles used (34). For example, the shank does not rotate as far forward in a low-bar wide stance squat (13). Without forward rotation, the moment arms through which vertical reaction forces act on the shank decreases, reducing the torque flexing the knee (15,16,35). A greater mechanical advantage allowing more weight to be lifted does not always equate to greater tension placed on the musculature.

Furthermore, if the muscles used change with the different techniques (16), the actual stimulus placed on each individual muscle would also change. In a narrow stance squat, whether using a front squat or high-bar back squat barbell position, the mechanical demand is distributed across the hip and knee extensors and ankle plantar-flexors (13). As the stance width increases, the demand placed on the ankle plantar-flexors decreases and the demand placed on the hip and knee extensors increases (13). With extremely wide stance widths, it is possible that the ankle dorsiflexors are required. Squats that do not allow the knees to move forward (ankle dorsiflexion) result in greater forward trunk lean (16), which increases loading of the lumbar spine (2). Therefore, the decision to use one technique versus the other cannot simply be made by considering which technique allows the most weight to be lifted.

A commonly made claim for using a wide stance squat, as well as the instructions to push the hips backward, is that squatting in this manner will train the “posterior chain” musculature. It must first be noted that the so-called posterior chain does not originate in the scientific literature, nor has it been subjected to scientific scrutiny. The first mention of the posterior chain (in English-language sources) was in an at-the-time popular bodybuilding magazine in the late 1990s. This term has since been propagated throughout other popular media and Internet and, recently, in some scientific articles. Originally, the posterior chain referred to the muscles on the posterior aspect of the lower extremity and pelvis, including the gastrocnemius, hamstrings, and gluteus maximus, which purportedly functioned synergistically and were invaluable for performance of sporting tasks such as running and jumping. However, there is no evidence that these muscles function synergistically during weight training or sports tasks.

In fact, the opposite may occur. For example, during the wide stance squat or sumo-style deadlift, the hip extensor demand increases while the ankle plantar-flexor demand decreases (13,14). During the snatch and clean, the gluteus maximus, quadriceps, and gastrocnemius work synergistically during the initiation of the first pull, followed by decreased ankle plantar-flexor demand and a shift from the knee extensors to knee flexors (i.e., hamstrings) at the end of the first pull to initiate the second knee bend (11,12). Similarly, during jumping, the gluteus maximus, quadriceps, and gastrocnemius activate in a proximal-to-distal sequence (25). The hamstrings are only activated at the end of the jump to contribute to propulsion and possibly limit knee hyperextension (25). Walking and running have even more complex muscle activation sequences (24), as opposed to the supposed synergistic activation of the posterior chain. Thus, it is clear that there is no special construct involving the gluteus maximus, hamstrings, and gastrocnemius that uniquely contributes to sports tasks. Therefore, the argument of modifying a squat for the purpose of training the posterior chain is specious because this construct does not exist biomechanically.

This does not suggest that training the hamstrings is not important. Several studies have reported the value of developing strength and flexibility in these muscles for performance and prevention of injuries (31). However, there is not sufficient evidence that such training is effective (29) for coaches to alter the general purpose of the squat exercise for developing strength of the hip and knee extensors and ankle plantar-flexors. As has been discussed previously, the technique of performing the squat with the torso upright, knees pushed forward, and weight centered across the forefoot and rearfoot distributes the mechanical loading across all the 3 muscle groups (7). This distribution of loading makes it effective for developing the bulk of the musculature in the lower extremity. Furthermore, the hamstrings have been demonstrated to activate when rising out of the deep squat position, typically at the region where the sticking point occurs (24,27). Other commonly performed exercises also train the hamstrings likely to a greater extent, such as the snatch, clean, and their variations, as well as deadlifts and good mornings (11,14).

THOUGHTS ON DEPTH

Concerns over squatting depth are commonly presented and are likely to have originated from Klein's work (30). Todd's analysis of Klein's work has suggested that below parallel squats, where the thigh and calf do not touch, were considered acceptable (30). This depth has been promoted by the National Strength and Conditioning Association in the Essentials of Strength Training and Conditioning text (10) and in a position stand (4). Research of squats performed to this depth demonstrates no negative effect on knee joint laxity and possibly an increase in knee joint ligamentous stability (5). Recent research has also cast doubts on the assertion that thigh-calf contact increases stress on the knee (36,37). Rather, contact of the thigh and calf generates a knee extensor torque, which would reduce the muscular demand of the quadriceps (36,37). The magnitude of the soft tissue contact-generated knee extensor torque appears to be large enough to substantially reduce the quadriceps tendon and patellar ligament forces, subsequently reducing patellofemoral joint forces and pressures. Although future research is required in this area, these data support the low incidence of knee injuries observed in competitive weightlifters (1), who typically perform some form of deep squats for hundreds of repetitions a week (17).

SUMMARY

A 4-stage progression is presented for teaching squatting exercise. This progression uses a previously unpublished variant that has been employed for teaching college athletes to squat for a number of years. The plate squat axially loads the cervical, thoracic, and lumbar spine. Theoretically, this loading will increase muscular activation to stabilize the spine, restricting intervertebral motion and forward trunk inclination. Once learned and practiced, the overhead squat and front squat are introduced and finally the back squat. For athletic performance, both the front squat and back squat are effective for increasing muscle mass, strength, and power. A narrow stance squat performed through a full range of motion will distribute the loading across the lower extremity joints and musculature, thus can be recommended for most individuals.

REFERENCES

1. Calhoon G and Fry AC. Injury rates and profiles of elite competitive weightlifters. J Athletic Train 34: 232-238, 1999.

2. Cappozzo A, Felici F, Figura F, and Gazzani F. Lumbar spine loading during half-squat exercises. Med Sci Sports Exerc 17: 613-620, 1985.

3. Carlock JM, Smith SL, Hartman MJ, Morris RT, Ciroslan DA, Pierce KC, Newton RU, Harman EA, Sands WA, and Stone MH. The relationship between vertical jump power estimates and weightlifting ability: A field-test approach. J Strength Cond Res 18: 534-439, 2004.

4. Chandler TJ and Stone MH. The squat exercise in athletic conditioning: A review of the literature. Strength Cond J 13(5): 51-58, 1991.

5. Chandler TJ, Wilson GD, and Stone MH. The effect of the squat exercise on knee stability. Med Sci Sports Exerc 21: 299-303, 1989.

6. Chiu LZF. Sitting back in the squat. Strength Cond J 31(6): 25-27, 2009. Ovid Full Text Where can I get this?

7. Chiu LZF and Salem GJ. Comparison of joint kinetics during free weight and flywheel resistance exercise. J Strength Cond Res 20: 555-562, 2006.

8. Cholewicki J and Van Vliet JJ IV. Relative contribution of trunk muscles to the stability of the lumbar spine during isometric exertions. Clin Biomech 17: 99-105, 2002.

9. Crisco JJ, Panjabi MM, Yamamoto I, and Oxland TR. Euler stability of the human ligamentous lumbar spine. Part II: Experiment. Clin Biomech 7: 27-32, 1992.

10. Earle RW and Baechle TR. Resistance training and spotting techniques. In: Essentials of Strength Training and Conditioning. Baechle TR and Earle RW, eds. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics, 2008. pp. 350-352.

11. Enoka RM. Muscular control of a learned movement: The speed control system hypothesis. Exp Brain Res 51: 135-145, 1983.

12. Enoka RM. Load- and skill-related changes in segmental contributions to a weightlifting movement. Med Sci Sports Exerc 20: 178-187, 1988.

13. Escamilla RF, Fleisig GS, Lowry TM, Barrentine SW, and Andrews JR. A three-dimensional biomechanical analysis of the squat during varying stance widths. Med Sci Sports Exerc 33: 984-998, 2001.

14. Escamilla RF, Francisco AC, Kayes AV, Speer KP, and Moorman CT III. An electromyographic analysis of sumo and conventional style deadlifts. Med Sci Sports Exerc 34: 682-688, 2002.

15. Flanagan SP and Salem GJ. Lower extremity joint kinetic responses to external resistance variations. J Appl Biomech 24: 58-68, 2008.

16. Fry AC, Smith JC, and Schilling BK. Effect of knee position on hip and knee torques during the barbell squat. J Strength Cond Res 17: 629-633, 2003.

17. Garhammer J and Takano B. Training for Weightlifting. In: Strength and Power in Sport. Komi PV, ed. Oxford, United Kingdom: Blackwell Scientific, 2003. pp. 502-515.

18. Gullet, JC, Tillman, MD, Gutierrez, GM, and Chow JW. A biomechanical comparison of back and front squats in healthy trained individuals. J Strength Cond Res 23: 284-292, 2008.

19. Gumbs VL, Segal D, Halligan JB, and Lower G. Bilateral distal radius and ulnar fractures in adolescent weight lifters. Am J Sports Med 10: 375-379, 1982.

20. Kritz M, Cronin J, and Hume P. The bodyweight squat: A movement screen for the squat pattern. Strength Cond J 31(1): 76-85, 2009.

21. McCaw ST and Melrose DR. Stance width and bar load effects on leg muscle activity during the parallel squat. Med Sci Sports Exerc 3: 428-436, 1999.

22. McGill SM, Grenier S, Kavcic N, and Cholewicki J. Coordination of muscle activity to assure stability of the lumbar spine. J Electromyogr Kines 13: 353-359, 2003.

23. Miller SJ and Smith PA. Volar dislocation of the lunate in a weight lifter. Orthopedics 19: 61-63, 1996.

24. Neptune RR, Kautz SA, and Zajac FE. Contributions of the individual ankle plantar flexors to support, forward progression and swing initiation during walking. J Biomech 34: 1387-1398, 2001.

25. Pandy MG and Zajac FE. Optimal muscular coordination strategies for jumping. J Biomech 24: 1-10, 1991.

26. Paoli A, Marcolin G, and Petrone N. The effect of stance width on the electromyographical activity of eight superficial thigh muscles during back squat with different bar loads. J Strength Cond Res 23: 246-250, 2009.

27. Robertson DGE, Wilson JJ, and St. Pierre TA. Lower extremity muscle functions during full squats. J Appl Biomech 24: 333-339, 2008.

28. Salem GJ, Salinas R, and Harding FV. Bilateral kinematic and kinetic analysis of the squat exercise after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 84: 1211-1216, 2003.

29. Simonsen EB, Magnusson SP, Bencke J, Næsborg H, Havkrog M, Ebstup JF, and Sønsen H. Can the hamstrings muscles protect the anterior cruciate ligament during a side-cutting maneuver? Scand J Med Sci Sports 10: 78-84, 2000.

30. Todd T.Karl Klein and the squat. Strength Cond J 6(3): 26-31, 67, 1984. Where can I get this?

31. Withrow TJ, Huston LJ, Wojtys EM, and Ashton-Miller JA. Effect of varying hamstring tension on anterior cruciate ligament strain during in vitro impulsive knee flexion and compression loading. J Bone Joint Surg Am 90: 815-823, 2008.

32. Wisløff U, Castagna C, Helgerud J, Jones R, and Hoff J. Strong correlation of maximal squat strength with sprint performance and vertical jump height in elite soccer players. Br J Sports Med 38: 285-288, 2004.

33. Wooten JR and Jones DH. An unusual weightlifting injury. Injury 19: 446-454, 1988.

34. Wretenberg P, Feng Y, and Arborelius UP. High- and low-bar squatting techniques during weight-training. Med Sci Sports Exerc 28: 218-224, 1996.

35. Wretenberg, P, Feng Y, Lindberg F, and Arborelius UP. Joint moments of force and quadriceps muscle activity during squatting exercise. Scand J Med Sci Sports 3: 244-250, 1993.

36. Zelle J, Barink M, De Waal Malefijt M, and Verdonschot N. Thigh-calf contact: Does it affect the loading of the knee in the high-flexion range? J Biomech 42: 587-593, 2009.

37. Zelle J, Barink M, Loeffen R, De Waal Malefijt M, and Verdonschot N. Thigh-calf contact force measurements in deep knee flexion. Clin Biomech 22: 821-826, 2007.