Bench Press History, Records and Raw Lifts

by Sean Katterle

Bench pressing began in a crude form in the 1930s, when lifters literally lay on a wooden “bench” or box and pressed a barbell up off their chests. For decades before that men had trained on different versions of the floor press. Some lifted while laying flat on the ground, and others would arch during the lift the way a wrestler bridges. The bridged version of the lift was often referred to as a “belly toss” because the pressing portion of the movement began with a back and leg arching maneuver to get the bar started.

People could obviously move more weight through belly tossing than through flat-backed floor pressing, but many recognized that it was not a true upper-body anterior strength test. Belly tossing was a form of “cheating” for the same reason that barbell swing-curling isn’t an accurate test of a person’s biceps strength. The flat-backed floor press was and is an excellent strength-building exercise, but you need a handoff person to work it properly.

In the ‘20s and ‘30s the proper technique in

John Sanchez, a noted powerlifting historian, explains why Hoffman felt the need to outlaw belly tossing as an official way to attempt a prone press: “After the rules governing shoulder bridge/belly toss technique were relaxed somewhat during the late 1920s, Bill Lilly was able to set many records due to his incredible flexibility. Lilly could slowly elevate the bar on his abdomen to complete arm lockout position. Some would take issue with this extreme maneuver, alleging it was more a contortionist’s trick than a genuine display of strength, but his records stood nonetheless. Apparently, Bill Lilly was so gifted with this new version of the shoulder-bridge movement that challenges to his 484 lb. record were nonexistent during the ‘30s.

“While the shoulder bridge or belly toss exercise may seem rather arcane nowadays, during its heyday it was a respected lift. Impelling a barbell off of one’s belly to the degree that such a maneuver required could not have been very easy or comfortable. Nevertheless, that was the only way lifters of that era were able to exceed double, or in the case of Lilly, nearly triple bodyweight while lying on their back.”

What’s ironic about the debate over belly tossing and flat-backed prone pressing was that nowadays some lifters have increased their flexibility on the raised “bench” to the point that their range of motion is basically cut in half, and overweight lifters use the combination of a tight-fitting bench press supershirt and a rotund power gut to do a soft handoff to the top of their belly and back again. They hardly have to move the bar vertically at all. They support the weight of the bar with the ultratight-fitting, reinforced bench shirt and then let the bar drift horizontally down their torso until it reaches the peak of their gut, which is very close to the same height as where the bar was handed off to them. When they get the press command, they simply drive it back toward their chest line and few inches upward to lockout.

The best way to keep those people from benching that way is to ban supershirts altogether and to insist that the lifter’s entire buttocks and shoulder blades remain in contact with the bench at all times. It’s okay to arch, as arching is a part of power-benching leverage and stability, but it’s got to be kept to a reasonable level. When the supershirts are removed from competition, the arching becomes less severe, and the heavyset lifters are forced to bring the bar up to their lower chest level. You can’t pull off the belly bench drift without the “support” of the shirt.

It was in the 1930s that trainees began using benches and boxes for the prone press. It enabled them to plant their feet on the floor while keeping their hips low and their butt and shoulder blades in contact with the bench or box. The AAU also approved the use of a spotter for handing off the barbell to the lifter so pressers could begin the lift with the weight in position over their chest.

All three variations of the press on back – prone floor press, belly toss and bench press – persisted relatively unchanged through the 1940s, but a hierarchy among them quickly developed. For bodybuilders the bench version gained dominance, and by the 1950s it was the king of upper-body movements, with noted advocates like Marvin Eder and George Eiferman. A major reason was that, as chest-conscious athletes, they liked its effect on the pectorals. John Sanchez further explains: “Interestingly, the bench press was to remain a somewhat controversial lift during the 1950s as lifters sought to maximize their advantage with outside help during its performance. What many would object to during these times would eventually become the status quo for the sport of powerlifting, however. Bench-pressing during the 1950s was an exercise in the throes of evolutionary ferment. The popularity of the lift as an aid to bodybuilders was responsible for the innovative development of rack stanchions, which some ‘traditionalists’ considered ‘cheating.’ Moreover, hand-offs as a means to get the barbell in place were similarly disdained by those who thought the best way to bench was by oneself, or unassisted.”

Prior to 1964 the sport didn’t have a national or world championship. Lifting competitions were held by independent groups of athletes and promoters, and aficionados of the sport were brought in to witness and credit the “record-breaking” feats of strength. One of the first acknowledged record holders in the press on back without a bridge was the famous German wrestler and strongman Georg Hackenschmidt. In 1898 he pressed 361 pounds – with 19-inch diameter plates – and it stayed in the record books for 18 years. He was eventually exceeded by Joe Nordquest, a heavyweight who pressed 363 pounds in 1916 – while using 18-inch diameter plates. A year later Nordquest would also set a record of 388 pounds in the belly toss, breaking the previous 386-pound record of German strength phenom Arthur Saxon. Among the heavyweights, an early record holder in the belly toss was George Lurich, a Russian wrestler who did 443 pounds in 1902.

Bench press stanchions – the uprights now seen on every make of pressing bench today – showed up in the 1950s, as did the first official 400-, 450- and 500-pound lifts. In November, 1950, Canadian Doug Hepburn became the first to officially pause 400 pounds. He did 450-plus (456 paused) exactly a year later and in December, 1953, made the first official 500-pound lift (502 pounds paused). Four years after that he barely missed the first 600- pound attempt. Hepburn also won a gold medal at the 1953 World Weightlifting Championship in

Though the Olympic lifting powers attempted to stop the odd lifts being performed in competition, they were unable to do so. One reason is that the odd lifts were some of the best for building muscle size and brute strength. What’s more, many of them – notably the squat, bench press and deadlift – didn’t require the flexibility and coordination that the modern-day Olympic lifts demand. In addition, those three moves, now known as the powerlifts, were the most accurate way of determining who the physically strongest person was. Olympic lifts decide who the strongest, quickest, most flexible and coordinated lifter is.

Many strongman lifts are multi-rep events that require conditioning and a different combination of fast-twitch and slow-twitch muscle fibers. Strongman competitions are usually designed to favor an athlete who’s taller than average and has a bigger bone structure in his hands. Powerlifting, without the supersuits and bench press shirts, is still the most accurate way to determine who’s truly the best at limit-strength lifting. Skeletal factors influence the lifts’ leverage, but the biggest squatters, benchers and deadlifters of all time are all right around 6’ tall and all have a relatively “normal” limbs-to-height ratio.

It was IronMan publisher Peary Rader who made the first strong move to get powerlifting sanctioned in the

“Nevertheless,” John Sanchez explains, “Peary Rader sought to provide a national meet venue for which AAU records could be officially set in the new AAU ‘power’ lift category. Had things gone according to plan, that would have been the first ‘national power lift championships’ ever organized and was scheduled for the Fall of 1959. Unfortunately, Rader’s national meet never came to pass. The first national powerlifting competition would not occur for yet another five years, only this time under the auspices of Strength & Health magazine’s publisher, Bob Hoffman.

When the 1960s rolled around, Pat Casey began to take the bench press scene by storm, and he posted his own 500-pound press. He would go on to become the first person to officially break the 600-pound barrier, and his career high was a 615-pound push on March 25, 1967. Pat Casey a highly accomplished powerlifter on all three lifts, and he was the first man to total 2,000 pounds in a meet.

Up through 1962, despite Peary Rader’s attempts, bench records were still not being kept, and it was up to muscle magazine reporters to keep tabs on who had lifted what. The press-or-no-press portion of the lift started getting a lot oaf attention because a lifter could dangerously add a lot of weight to his bench by trampolining the bar off his gut or ribcage.

Bill Pearl wrote about Pat Casey: “I was afraid the benches would not hold the weight. He would do chest exercises with a pair of 220-pound dumbells. There was a corner of the gym where Pat stored his weights for special lifts. Nobody touched Pat’s weights. Nobody other than Pat wanted to touch his weights.”

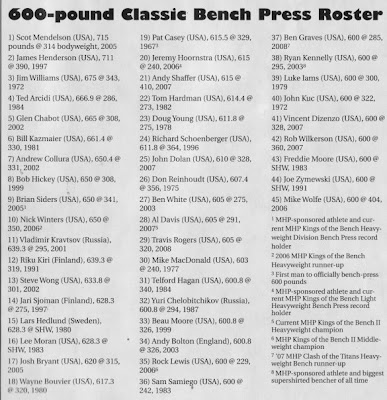

Pat Casey became the first 600-pound bencher in history just 40 years ago. To this day the 600-pound classic bench press is one of the greatest strength feats an athlete can perform. When I say “classic” I mean a traditional bench press where a lifter gets the weight handed off to him on a bench and can chalk his hands and use wrist wraps and a lifting belt. Lifters can’t use elbow wraps or a bench press shirt and can’t raise their butts or shoulders off the bench, and they have to complete the lift using a full range of motion, with arms fully locked out at the end of the press. The 600-pound Classic Bench Press Roster above is a who’s who of the greatest heavyweight benchers the sport of powerlifting has ever seen. A 600-pound bench done without a supershirt is a remarkable achievement that takes years of dedication, and these athletes should be recognized for their incredible strength accomplishments.