Subscribe:

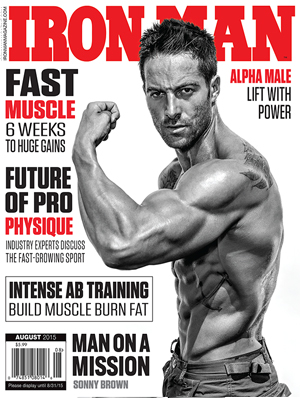

Articles by Alexander Juan Antonio Cortes

Controlled Overtraining Can Lead to

Dramatic Short-Term Results

Overtraining can beat you up and leave you injured. But done strategically, it can also get you into peak shape in record time, while making some of the best short-term gains of your life.

Building muscle is a long-term process. Tissue can only be added so fast, and muscular density is developed from thousands upon thousands of repetitions. For those who want an aesthetic physique, patience is part of the game. That said, there are times when planned overtraining can deliver phenomenal short-term improvements. While you cannot "train insane" every day, there are periods where absolutely blasting it in the gym can kick you out of a rut and spur improvements in both muscle mass and strength.

Within exercise science, the term for this planned overtraining is "overreaching" and refers to distinct periods of time in which training volume, intensity, and frequency are increased for the purpose of shocking your physiology into improvement.

Time to Triple Up

This program works on a compressed time frame. That means training is going to be put into overdrive. Specifically, we are going to utilize three different training methods all at once to push the intensity of the workouts. Over six weeks, you'll dramatically transform your physique through a carefully periodized plan that has you training all out every session, but which ceases before the point of burnout or injury.

These strategies we'll be using are compensatory acceleration training (CAT), relative strength method, and giant sets.

Compensatory Acceleration Training

Formulated by sports scientist Dr. Fred Hatfield, this method focuses on moving weights with maximal acceleration on every single rep. Similar to the concept of the Dynamic Effort method created by Louie Simmons of Westside Barbell, CAT focuses on power an strength development with your working weights. CAT sets are all about speed and explosiveness. If you're doing a bench press on a CAT day, the bar will come down slowly but should explode off your chest and reach the end of its range of motion as quickly as possible. On these sets, you will always stop short of grinding out reps or using a weight that is so heavy it makes you slow.

Relative Strength

This simply refers to using your bodyweight as resistance. While bodyweight movements are sometimes dismissed as being ineffective for building muscle, they can have a hypertrophic effect. Since they're less taxing on the joints than free weights, you can also perform them at a higher volume and more frequently. Because they can also be done for very high reps, they can be used for HIIT (high intensity interval training) and have a metabolic effect when incorporated into training. To become stronger relative to your weight, your body must also shed extraneous tissue. Developing relative strength will also have positive carryover with all your traditional lifting exercises.

Giant Sets

Giant sets are performed in circuit fashion but are bodypart specific, designed to use complementary exercises for the same muscle group in sequence. Giant sets enable you to lift "giant" amounts of volume within a compact time frame. This elevates the metabolic factors of the workout, creating a powerful stimulus that can develop hypertrophy and help shed excess body fat.

Six-Week Assault

Over the next six weeks, you will be training six days a week, working a three-day bodypart split. Over the course of the week, every muscle group will be trained twice. You will alternate between CAT days for power and strength, and giant set days for massive metabolic disruption. Sprinkled throughout will be relative strength bodyweight work, along with regular repetition work.

The main concept here is to blast through every workout. Don't worry about increasing the weights. Rather, aim for moving the same weights for more reps and more quickly, with control and authority. The idea here is to maximize speed and volume. Add reps and sets before adding weight to any one exercise. Take as little rest as possible. Rest only as long as you need to perform the next set and then start again at full bore.

The main concept here is to blast through every workout. Don't worry about increasing the weights. Rather, aim for moving the same weights for more reps and more quickly, with control and authority. The idea here is to maximize speed and volume. Add reps and sets before adding weight to any one exercise. Take as little rest as possible. Rest only as long as you need to perform the next set and then start again at full bore.

The Science of the Triple Threat

This training program is designed to create a powerful short-term anabolic effect, not a long-term change. With that in mind, this is not a year-round training program the repeat over and over. In exercise science terminology, we're creating an acute response. This will require intense exposure and application of stimulus. That means you're in for some punishing workouts.

Why does blasting hard work so well for building muscle? The initial response of a body to an increase in volume and frequency is to overcompensate its adaptive mechanism. For a short period of time, your metabolism will be highly elevated and your recovery will increase to accommodate the training stimulus. This is a natural response to stress. Instead of making you slow down, your physiology will focus upon surviving and overcoming the stress you're placing on it.

This effect quickly subsides, however, usually when the stress continues past four to six weeks. And beyond the six or seven week mark, metabolism will start to gradually dip as your body tells you to slow down and stop expending so much energy.

This creates a window to build some muscle and opportunity to shed some body fat at the same time. That is why this program is six weeks in length.

By creating an acute effect through the right type of training, your physiology will be "shocked" into rapidly adapting. And you'll emerge looking the sharpest you've ever looked within such a short period of time.

Training Split

Monday: Quads/Hamstrings (CAT)

Tuesday: Chest/Back (CAT)

Wednesday: Shoulders/Arms (Relative Strength + Giant Set)

Thursday: Quads/Hamstrings (Relative Strength + Giant Set)

Friday: Chest/Back (Relative Strength + Giant Set)

Saturday: Shoulders/Arms (CAT)

Sunday: Rest

Wednesday: Shoulders/Arms (Relative Strength + Giant Set)

Thursday: Quads/Hamstrings (Relative Strength + Giant Set)

Friday: Chest/Back (Relative Strength + Giant Set)

Saturday: Shoulders/Arms (CAT)

Sunday: Rest

Monday: Quads/Hamstrings (CAT)

Back Squat, 5 x 5 superset with

Double Kettlebell Swing, 5 x 10.

Barbell Jump Squat, 6 sets of 3 reps.

Stand in a conventional squatting position with a barbell on your back, your feet at shoulder width, and your hands gripping the bar tightly. Push your hips back and descend into a parallel squat with your head and chest up. Explode from this bottom position into a jump, then land softly and descend into another squat in a smooth, controlled manner.

Stiff-Legged Dumbbell Deadlift, 3 x 15.

Leg Press Drop-Set, 5 x 40-20-10.

Explosive Standing Calf Raise, 4 x 5.

Tuesday: Chest/Back (CAT)

Incline Barbell Press, 5 x 5.

Bentover Barbell Row, 5 x 5.

Dumbbell Squeeze Press, 4 x 15 superset with

Hammer Strength Row, 4 x 15.

Dumbbell Bench Press, 3 x 12.

Bentover Dumbbell Row, 3 x 10.

Close-Grip Lat Pulldown, 2 x 12.

Incline Dumbbell Flye, 3 x 15.

Wednesday: Shoulders/Arms (Relative Strength + Giant Set)

Supinated Close-Grip Chinup, 4 x as many as possible, superset with

Close-Grip Triceps Pushup, 4 x as many as possible.

Giant Set: 3 rounds with movements performed in sequence -

Seated Machine Shoulder Press, 10 reps

Triceps Pushdown, 15

Seated Dumbbell Curl, 10

Dumbbell Lateral Raise, 20.

Thursday: Quads/Hamstrings (Relative Strength + Giant Set)

Sumo Deadlift, 3 x 10.

Bodyweight Split Squat, 3 x 10-20.

45-Degree Hyperextension, 3 x 20.

Giant Set: 3 rounds with movements performed in sequence -

Bodyweight Squat, 20 reps

Lateral Lunge, 12 (each leg)

Bodyweight Reverse Lunge, 10 (each leg)

Bodyweight Jump Squat, 15.

Friday: Chest/Back (Relative Strength + Giant Set)

Supinated Close-Grip Chinup, 5 x 6-12, superset with

V-Bar Dip, 5 x 8-15.

Giant Set: 4 rounds with movements performed in sequence -

Pushup (moderate grip), as many as possible

Inverted Row, as many as possible

Wide-Grip Pullup, as many as possible

Deficit Pushup, 15.

Saturday: Shoulders/Arms (CAT)

Single-Arm Dumbbell Snatch, 6 sets of 3 reps.

Strict Barbell Curl, 5 x 5.

Push Press, 5 x 4.

Close-Grip Plyo Pushup, 5 x 5 superset with

Bench Press, 5 x 6.

Barbell Hang High Pull, 3 x 12.

Seated Dumbbell Hammer Curl, 3 x 10.

Triceps Pushdown, 3 x 20.