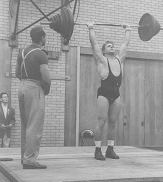

1200-pound 1/4 squats at 198 bodyweight

First Middleweight at 198 to Clean & Jerk 400 pounds.

Here, with 409.

At 90, strength coach for the Chicago Bears.

CLYDE EMRICH:

A Bear on Strength

by Paul E. Young

In the relatively few years that I have been involved in the strength training profession, I have had the good fortune to visit with some of the top people in the field. At one time or another, they have all mentioned Clyde Emrich as someone who has has a profound influence on them, not only professionally but personally.

As a weightlifter, Clyde's career extended from 1947 to 1968. During those years, Clyde competed nationally and won internationally. He won numerous state and regional titles, set national and world records, competed in the Olympics, and was one of our country's top weightlifters in his day.

Clyde's coaching career is no less impressive. He has been with the Chicago Bears for 23 years. He was one of the first strength coaches in the NFL. He is regarded as many as the elder statesman in the strength coaching profession. His advice and counsel are continually sought by his peers.

Question, Paul E. Young: How did you get started lifting weights?

Answer, Clyde Emrich: My first exposure was when I was 10 or 11 years old, watching some kids lift in a basement. I thought it was quite interesting. When I was 15 or so, I bought some stretch cables and started making my own weights out of weighted cans of sand and cement. I started performing the exercises that I saw in Strength & Health and other magazines at the time.

Q: Did you have a coach that helped with your training?

A: No . . . never had a coach.

Q: What about later in your lifting career?

A: No, I was always self-coached. I knew that if I wanted to develop certain muscles I had better understand how they worked, so I would go to the library and read and study books on kinesiology and anatomy. I knew if I wanted to make my muscles stronger and bigger that diet was important, so I read everything I could on nutrition. I taught myself how to lift by trying to copy the pictures in the magazines. Sometimes I would wonder how they could get into such position. Later I would see a photograph sequence of the exercise, which would then answer my questions.

I trained in my basement, performing snatches, clean and jerks, presses and squats. Even right up to the 1952 Olympics in Helsinki, my training was done in my basement. Also, all my training was done with an exercise bar, not an Olympic bar with revolving sleeves. I feel that this actually helped my pulling power as I had to have greater strength to elevate this stiff non-revolving exercise bar as opposed to a springier Olympic bar. I also never used lifting straps of a hook grip. I remember one time performing jerks off a rack in my basement with health shoes hanging on the ends of the bar for added weight. Since the largest plates I had were 25 pounds, I had to place bricks or boards under the weights to get the bar to approximately the right height to perform my lifting.

I have always loved lifting weights. I think that I enjoyed training just as much or maybe more than competing. On days that I was to train, I remember waking up in the morning and thinking to myself, "All right, I get to train today."

Q: Did you have any lifters that you looked up to or tried to emulate?

A: John Davis, of course. I really admired his lifting ability. Pete George was outstanding. Great technique. I was impressed with Pete because he was so strong for not being excessively muscular. Stan "The Flash" Stanczyk had incredible pressing power and great technique. Tommy Kono was an outstanding lifter and a good friend.

John Davis was a real hero. I remember a lifting contest I was at in New York -- in the training hall were all of the great lifters of the day. John Davis walked over to me and said, "You're Clyde Emrich, aren't you?", and we visited briefly. What a treat. Here was the great John Davis coming over to talk to me, Clyde Emrich. That made a lasting impression upon me -- what a great person.

Q: Did you participate in any other sports or were you strictly a weightlifter?

A: Just a weightlifter. I was always quick and played neighborhood games, but I only competed in weightlifting. I have a son who has run 100 yards in 9.93, so I think there is some speed and quickness in the family.

When I started out lifting I didn't start out to be a weightlifter. I didn't know the difference between bodybuilding and weightlifting. I performed the snatch for the same reason as anyone else would perform arm curls -- it was an exercise I used to get stronger.

Q: How did you get into strength coaching?

A: In the early 1960s when isometrics were coming into use, I was training at the Irving YMCA. Six to eight of the Chicago Bears players worked out there, and they asked me if I could help them. Word got back to the Bears' staff and George Halas got a hold of me and asked if I could set up a training program for the team. George Halas was always looking for an edge. I set up a training program for the team in 1963, and coincidentally the Bears won the championship that year. Now, what role that played I don't know but it's fun to speculate.

Q: How would you describe your strength coaching philosophy?

A: Athletes should train how they are asked to perform on the field. The multi-joint explosive lifts are the best to achieve this. I believe in what I call the body core exercises. The areas of the body that we need to train are the legs, back and shoulders. Something that I think is very important is that you should do as many exercises as you can while standing on your feet. I don't know of a sport where you push up while lying on your back.

It is important to remember that you cannot substitute strength for skill. Your good athletes have a genetic gift for performing movement skills. You cannot spend more time getting stronger in the hopes that it will automatically improve your performance on the field. You have to have the athletic talent first.

Q: How would you describe the difference between weightlifting and strength training?

A: You use the weightlifting exercises or their variations to increase an athlete's strength, to prevent injuries and improve their performance on the field. You do not peak strength as you would with weightlifting. Technique may not be as sharp as a weightlifters.

Q: What are your feelings regarding free weights and machines?

A: Free weights are the best. But I like to think of exercises, barbells, dumbbells, and machines as tools of the trade. Just like a carpenter has a different tool for a specific job. Machines don't allow you to isolate a certain muscle or movement, which you may need to do to work around an injury, to rehabilitate an area, or to correct a specific weakness.

Cleaning 400 pounds, en route to a world record clean & jerk in 1957.

Ideally, I think you can do the best job in strengthening an athlete with free weights, but in reality when a player has had four or five knee operations and other injuries over the years, you need to be flexible in your strength training program. It has been interesting in my years with the Bears to watch the evolution of a player's strength training program. He may start his career with primarily free weight exercises, and by the end of his career his program may be primarily machines.

I like to make the comparison of multi-joint free weight exercises to a football team. They are both a collective and coordinated effort. For both of them to be successful, all those involved must function as a unit. One can't do it without the help of all the others.

As a general rule of thumb, I use 1 to 5 repetitions on barbell exercises, 5 to 10 reps on dumbbell exercises, and 10 to 20 on machines.

Q: How do you feel about the so-called "training secrets" that some people purport?

A: I haven't seen anybody do anything that I hadn't seen John Grimek do.

The super sets, giant sets and master blaster routines are nothing more than variations on multiple set training. The biggest change that I have seen has probably been the use of steroids. I feel that some of the weight training cycles and periodization used in strength training today have their roots in steroid cycling. I cannot and will not ever condone the use of steroids.

If you want to know the secret to training, it is this -- to get strong you have to lift heavy weights. You must work the legs, back and shoulders. All the strong men like Doug Hepburn, Paul Anderson, Charles Rigoulot, Hermann Goerner and others used basic movements and trained them heavily in order to get strong.

Q: Do you train the skill positions (quarterback, running back, receiver, defensive back) any differently than the rest of your team?

A: No. There may be some minor variations, but basically I train them all the same. The weights used will obviously be different from athlete to athlete, but what I am trying to accomplish is the same.

Q: Are there any trends that are disturbing to you as a strength coach?

A: I feel there is too much bodybuilding in strength training. Bodybuilding is fine for bodybuilding, but if you are going to perform on the field, you had better train in a manner that complements this. This is why your multi-joint lifts and explosive lifts are the best. Bodybuilding has some application for rehabilitation, but your multi-joint athletic lifts should be your foundation.

If bodybuilding was the correct way to train for sports, you would see a lot of bodybuilders out there on the fields and courts. And you don't see that. This is not to knock bodybuilding, but if you are going to be asked to perform as an athlete, you had better train as an athlete.

Q: If you could design the ideal training program for an athlete (whose sport requires speed, quickness, agility, strength, and power), what would it look like?

A: Again, getting back to the core exercises that I have mentioned earlier, you must strengthen the legs, back and shoulders. Power cleans and snatches, overhead pressing, squatting, bentover rowing, bench pressing, basic plyometrics, and running. I would use dumbbells as much as possible. THE DUMBBELL POWER CLEAN is a particularly great exercise for football players.

I try to use the push/pull method in my programs. Something we as strength coaches have gotten away from, but what I think we need to work more on is direct pressing overhead. We have incline, decline, and flat bench presses that we work on but I really believe that we need to do more overhead pressing.

I think uphill running is a good exercise. I think some over-speed running on a very slight decline is quite good. An exercise that we used in the past which was quite effective was jumping up onto a 32" table while holding dumbbells. We would work up to holding 45 pound dumbbells and then we gradually increased the height of the table to 42".

Q: Do you cycle your players' workouts?

A: I have not been one to follow a heavy, light, medium type of training. My feeling toward lifting is to "grab the moment." I can't see using a light weight on a day that I feel strong. I always trained ins this fashion as a lifter, and I use the same basic principle with my athletes, but with some modifications. I think that you should use as heavy a weight as you can for the prescribed number of repetitions during a workout.

Now for our strength training purposes, we don't take the weights right to the limit as I would as weightlifter because our goals are a bit different. If an athlete is feeling strong, we may keep the reps constant and pyramid the weight up to a good hard effort on the last set. If he is not quite up to going this heavy, we will perform what I call a muscle workout, sets and reps with a constant weight, for example. I always talk with my athletes and get their feelings on how they feel before and during a workout. I feel that it is important to get the players involved in their workouts. This gives them some input into their program, and this input gives them ownership and with ownership comes responsibility.

Author's note: Clyde used this method of heavy training back in the 1940s through the 1960s. It is interesting to see many of the top Olympic lifters in the world today using these very same methods in their training, and these very same methods are what some people are calling a "new and revolutionary type of training."

Q: Is every workout the same?

A: No. Using the guidelines I mentioned earlier (1-5 reps with barbells, 5-10 with dumbbells, and 10-20 with machines), we do a different type of workout each day of the week. For example, over the course of our four day per week lifting routine, we might perform a barbell exercise on Monday, a dumbbell exercise on Tuesday, and do some type of machine exercise on Friday for the same body core part. I also try to mix things up by changing exercises, sets and reps, pyramiding weights, constant weights and so forth. Always with the athlete's input and always flexible.

Q: Do you do any strength testing?

A: No, not really. We do the NFL bench press test of 225 pounds for reps, for whatever that's worth. We may do some other testing depending on the wishes of the coaches. In 1985, when we won the Super Bowl, we did no testing.

I know if a player is getting stronger by observing him during his workouts. Some absolute number is not going to tell me something that I don't already know.

Remember, we are strength training athletes, not training weightlifters.

The only time numbers on a board mean anything is at a weightlifting contest. I will never compare athletes as far as how much weight they can lift on an exercise. I don't say this athlete can only handle 205 on this exercise and another athlete handles 425. If the 205 athlete was handling 200 a week ago, I will give him a pat on the back and tell him, "great job, you're getting stronger."

Q: What role does genetics play in the grand scheme of things?

A: Oh, without question, genetics is the most important factor. Everybody can be made stronger. We all have a special genetic gift, and the athletes that I get to work with are certainly blessed. What makes them good athletes is that they possess the gift of athletic ability.

Something that I feel is important in dealing with athletes is that we need to strengthen their strengths. We should not spend a great deal of time trying to improve their weaknesses. They made it to this level due to some inherent ability. It's like the old saying, "You gotta dance with the one that brought you to the dance."

Q: You deal with athletes who come from varied strength training backgrounds (experience and philosophy). How do you handle this unique challenge?

A: I never discourage or discredit what somebody else does or what another coach does. I observe an athlete train and I will give my advice if I feel that they may benefit from a modification in their training. I like to sit down with the athlete and explain to them why modification may be of help to them. Teaching is a very important aspect of coaching.

Q: What do you like best about being a strength coach?

A: The think that I like the best is seeing an athlete progress and get better.

Q: What would you say to someone who is thinking about going into the strength coaching profession?

A: I feel that it is an outstanding profession. Education is very important -- learn as much as you can. You must be flexible in your program design and you must remember that you are strength training athletes and not training weightlifters.

It is my feeling that strength training has had the greatest effect on the improvement of athletic performance more than any other variable. This holds true for track and field, basketball, volleyball, and every other sport.

Make the training experience a positive one for your athletes, especially the ones who are not real big on strength training.

Always encourage your athletes, never put them down. You need to get along with your athletic trainers and your other coaches. After all, you re all working toward the same goal. It's not that tough to get along with everyone.

Q: Do you still work out?

A: Yes, I try to work out some. I do some deadlifting and overhead presses.

Q: You have had some health problems in recent years; how are you doing?

A: Several years ago I was in a weight room accident. I was spotting an athlete and someone walked behind me and bumped me, as our weight room is somewhat cramped for space. As I stepped back to catch my balance, I caught my foot on a hyperextension bench and fell and ruptured my quadriceps tendon. It was surgically repaired, but I still do not have full range of motion and strength.

A year ago this past February, I had been having some neck problems which were thought to be degenerative joint changes. I was told to have an MRI to determine the extent of these changes. The MRI showed that I had a tumor growing in the middle of my spinal cord. This is a very rare type of tumor, I was told. I underwent extensive surgery on my cervical spine and spinal cord. They had to cut into the middle of my spinal cord to get to the tumor.

I was left with some paralysis on my left side. I am improving, but it is slow going. Being left handed, the paralysis on the left side has me unable to write, which is frustrating. Without the surgery, the doctors said I would have been dead within six months. Other than that, things are going quite well.

Q: Looking back on your life as a competitive lifter and a strength coach, would you do it all again?

A: Oh, absolutely! Without a question. It has been great!

Enjoy Your Lifting!