Should You Give 100% All the Time?

by

Norman Zale (1991)

"He maxes out on every set."

How many times have you heard some 'expert' say that kind of thing. Or, to make it even more ridiculous, "Ol' Johnny gives 110% every workout."

What the expert may (hopefully) really be trying to say is that the bodybuilder always exhibits total concentration and dedication to his workouts; he never quits trying. Ergo, he must be giving "110 % effort.

Unfortunately, many lifters interpret this literally, especially beginners embarking on a bodybuilding program. They begin believing that to achieve results they must exert maximum effort at every workout.

No one, not even the best developed, can give 100 % at every workout. It is physiologically impossible. A person cannot train that way. If any champion bodybuilder or lifter actually trained that way at every workout they wouldn't last more than a couple of weeks at the longest. They'd drop from exhaustion and injuries.

Lee Haney, multiple Mr. Olympia winner, puts out a maximum or near maximum effort for each bodypart no more than once a week, and for the most part even less often than this. This is not to imply that his other workouts are easy, with little or no effort and stress. Not at all. Many of them are physically stressful, but not all of them are all-out 100 %.

Repeated all-out or near all-out workouts do not provide the body with enough time and energy to recover and may, therefore, cause staleness or a regression in strength and muscular development. Picture a beginner starting a program with the idea that each workout must be a total effort. Before long the misguided soul will be unable or unwilling to continue, and either quit altogether or start thinking the whole thing is a lie and a waste of time.

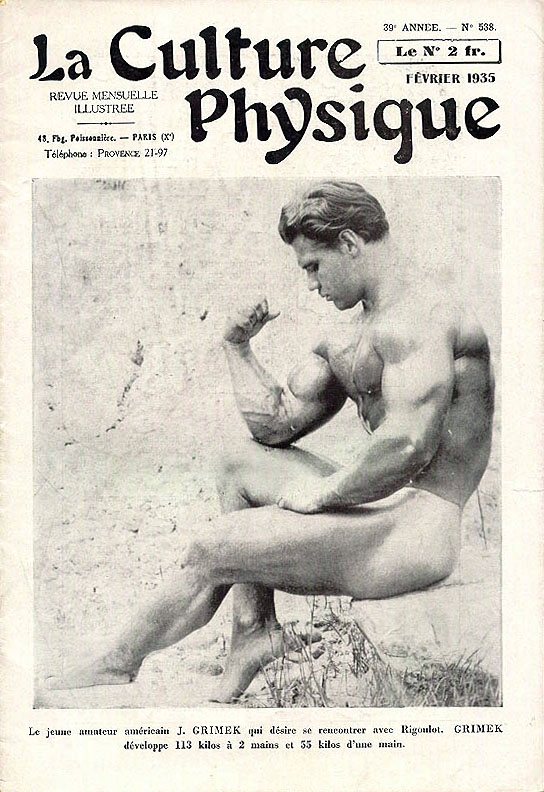

A bodybuilder, or any athlete (hobbyist or elite) cannot continue to do more and more each day without adequate recovery and recuperation, for it is during this non-workout time that the muscles grow larger and/or stronger. One of the primary reasons that many people fail to stick with a program is that they push themselves too hard each workout because they have been misled about how hard they are required to train to make satisfactory progress. Photos in the magazines of top lifters working (or posing as if working) to the max can be a misrepresentation of what their day to day workout intensity. And if a highly skilled and experienced bodybuilder or lifter cannot sustain daily max or near-max effort, how can an intermediate or beginner?

There are two basic principles that must be observed if you expect to make progress with your training program:

1) your body and muscles must be subjected to greater stress than they are accustomed to, and

2) appropriate recovery time must be allowed.

The muscles that are subjected to slightly greater stress than usual will respond to the stress by growing stronger and/or larger. They will adapt during the recovery or rest period and will then be ready for additional stress.

If, however, the stress is too great or the recovery is insufficient, your body will not adapt, and little or no improvement will occur. In fact, you may actually deteriorate by suffering an injury, getting weaker and/or losing muscle size.

Remember, the body building process does not occur while you are exercising -- the stress provided by the exercising merely provides the opportunity for improvement. The repair and development occur during recovery, be it passive or active.

Your body generally requires 36 to 48 hours to recover from a hard workout, and this can vary in each individual at different times. It has been reported that it requires 10 to 14 days to recover from the all-out type of effort that elite marathon runners put out during their 26 mile jaunts. Aren't you glad that you lift weights!

Your muscles consume a great deal of glycogen -- the sugar used for contractions -- during a strenuous workout, and it takes time for your body to refuel, to restore glycogen to the muscle tissues, longer if your diet has been deficient in certain nutrients. Repeated heavy workouts, day after day, can cause a serious glycogen depletion, resulting in exhaustion. However, each time the glycogen level is lowered by your training, the tissues tend to super-replenish glycogen.

After a workout, your muscles can absorb a greater supply of glycogen, provided an adequate recovery period is allowed and appropriately sufficient nutrients are ingested. The increase in your muscles' capacity to absorb glycogen is a key factor in developing both muscle size and endurance.

The repair of stressed muscle fibers and connective tissue also occurs during recovery. Muscle soreness is largely caused by micro trauma, microscopic tears, and damage to the muscles. These tissues need time to repair. The repair eases the soreness and helps to develop larger and/or stronger muscles.

It is important to keep in mind that recovery does not necessarily mean complete rest. It will often occur more quickly where heavy, stressful workouts are followed by milder and lighter workouts. The increased circulation from the easy-type training accelerates the recovery process.

To put this into practice, a six-day bodybuilding split might look like this:

Monday - Heavy chest/back.

Tuesday - Light lower body.

Wednesday - Heavy shoulders/arms.

Thursday - Light chest/back.

Friday - Heavy lower body.

Saturday - Light shoulders/arms.

As you can see, each bodypart, or group of muscles (or lift if you're more of a lifter than a bodybuilder), is worked twice a week. Note that heavy workouts are alternated with light workouts and it is not necessary, as many do, to take all their heavy workouts in a row and then follow with all of the lighter and medium workouts.

It is not just the same muscles but the whole body that must recover before muscle growth and/or strength will take place.

Yes, train hard and heavy but follow each heavy workout with a light training session, one that makes you feel glad that you came to the gym.

Repeated all-out or near all-out workouts do not provide the body with enough time and energy to recover and may, therefore, cause staleness or a regression in strength and muscular development. Picture a beginner starting a program with the idea that each workout must be a total effort. Before long the misguided soul will be unable or unwilling to continue, and either quit altogether or start thinking the whole thing is a lie and a waste of time.

A bodybuilder, or any athlete (hobbyist or elite) cannot continue to do more and more each day without adequate recovery and recuperation, for it is during this non-workout time that the muscles grow larger and/or stronger. One of the primary reasons that many people fail to stick with a program is that they push themselves too hard each workout because they have been misled about how hard they are required to train to make satisfactory progress. Photos in the magazines of top lifters working (or posing as if working) to the max can be a misrepresentation of what their day to day workout intensity. And if a highly skilled and experienced bodybuilder or lifter cannot sustain daily max or near-max effort, how can an intermediate or beginner?

There are two basic principles that must be observed if you expect to make progress with your training program:

1) your body and muscles must be subjected to greater stress than they are accustomed to, and

2) appropriate recovery time must be allowed.

The muscles that are subjected to slightly greater stress than usual will respond to the stress by growing stronger and/or larger. They will adapt during the recovery or rest period and will then be ready for additional stress.

If, however, the stress is too great or the recovery is insufficient, your body will not adapt, and little or no improvement will occur. In fact, you may actually deteriorate by suffering an injury, getting weaker and/or losing muscle size.

Remember, the body building process does not occur while you are exercising -- the stress provided by the exercising merely provides the opportunity for improvement. The repair and development occur during recovery, be it passive or active.

Your body generally requires 36 to 48 hours to recover from a hard workout, and this can vary in each individual at different times. It has been reported that it requires 10 to 14 days to recover from the all-out type of effort that elite marathon runners put out during their 26 mile jaunts. Aren't you glad that you lift weights!

Your muscles consume a great deal of glycogen -- the sugar used for contractions -- during a strenuous workout, and it takes time for your body to refuel, to restore glycogen to the muscle tissues, longer if your diet has been deficient in certain nutrients. Repeated heavy workouts, day after day, can cause a serious glycogen depletion, resulting in exhaustion. However, each time the glycogen level is lowered by your training, the tissues tend to super-replenish glycogen.

After a workout, your muscles can absorb a greater supply of glycogen, provided an adequate recovery period is allowed and appropriately sufficient nutrients are ingested. The increase in your muscles' capacity to absorb glycogen is a key factor in developing both muscle size and endurance.

The repair of stressed muscle fibers and connective tissue also occurs during recovery. Muscle soreness is largely caused by micro trauma, microscopic tears, and damage to the muscles. These tissues need time to repair. The repair eases the soreness and helps to develop larger and/or stronger muscles.

It is important to keep in mind that recovery does not necessarily mean complete rest. It will often occur more quickly where heavy, stressful workouts are followed by milder and lighter workouts. The increased circulation from the easy-type training accelerates the recovery process.

To put this into practice, a six-day bodybuilding split might look like this:

Monday - Heavy chest/back.

Tuesday - Light lower body.

Wednesday - Heavy shoulders/arms.

Thursday - Light chest/back.

Friday - Heavy lower body.

Saturday - Light shoulders/arms.

As you can see, each bodypart, or group of muscles (or lift if you're more of a lifter than a bodybuilder), is worked twice a week. Note that heavy workouts are alternated with light workouts and it is not necessary, as many do, to take all their heavy workouts in a row and then follow with all of the lighter and medium workouts.

It is not just the same muscles but the whole body that must recover before muscle growth and/or strength will take place.

Yes, train hard and heavy but follow each heavy workout with a light training session, one that makes you feel glad that you came to the gym.