So far, in this series, we have considered principally the upper arm . . .

. . . although it was pointed out that curling was very effective also for the flexor muscles of the forearm.

In most cases, however, the upper arm responds more readily to exercise than do the forearms. Perhaps the reason for this is that those muscles of the forearm which move the fingers are so frequently or habitually brought into mild action during the course of an average workday that nothing short of very vigorous specific exercise will affect these muscles sufficiently to cause much change in their size and strength.

In any event, fine forearms are less commonly seen than fine upper arms, even among barbell practitioners in whom the forearm muscles presumably receive much exercise. So often, indeed, is this the case that instances in which the forearm is proportionately developed are apt to be looked upon as something out of the ordinary.

On the other hand, in slender, undeveloped beginners the measurement of the forearm is only a little smaller than that of the straight upper arm. This indicates an ordinary upper arm, and that stout persons whose work is light have upper arms larger in proportion than their forearms only because of a larger accumulation of fat on their upper arms.

In dealing with forearm development, one must refer constantly to the fingers and hands, since it is the movements of these parts which cause contraction of, and so exercise, of the forearm muscles.

Observing anatomical diagrams will show that the wrist is simply a knuckle joint made up chiefly of bones, and of tendons which connect the bones of the hand with the muscles of the forearm. A broad, flat, tough ligament runs transversely around the wrist joint to hold the bones and tendons firmly in place.

The statement has by some writers been made that large wrists are a great advantage in all feats of strength, including weight-lifting proper. This is true only where there exists, in addition to large wrists, a reasonably equivalent development of the forearms. That is to say, a small wrist with a splendidly developed forearm may be fully as strong as a larger wrist accompanied by a less well-developed forearm.

Thus there have been strong-men noted for their forearm strength who had relatively large wrists, as for example, "Apollon," Arthur Saxon, Hermann Goerner, Ernest Cadine, and paul von Boeckmann. Again, there have been similarly distinguished strong-men who, in comparison with their muscle girths, had "small" wrists, such as Sandow, Louis Cyr, Thomas Inch, and the present-day champion, John Davis. Moreover, there must be hosts of high ranking Egyptian, Korean, and East Indian strong-men and weight-lifters whose wrists are racially slender.

The significant point, therefore, is that one may, through persistent training, acquire a strong forearm and "wrist" regardless of whether the actual size of the wrist be large or small.

As implied before, the regular two-arm barbell curl and the reverse curl, in addition to developing the flexor muscles of the elbow, have also a strong effect on the wrist. The regular curl (that is, with the palms upward) develops the front forearm muscles that flex the wrist. The reverse curl (with backs of the hands upward) develops the back forearm muscles that extend the wrist. The curling of a dumbbell, or a pair of dumbbells, with the handle of the bell held fore-and-aft, develops the abductors of the wrist, or those top-forearm muscles which bend or sustain the hand toward the thumb side.

Another form of curling, especially effective for strengthening the "wrist," is that variation, previously mentioned in connection with biceps development, in which a dumbbell is curled while maintaining the body in a semi-reclining position on the floor.

In this exercise the upper body faces sideward and is rested on the elbow of the curling arm (which, as previously advised, should rest on something soft!). This fixed position of the elbow enables the developing effect of curling the weight to be directed particularly to the forearm. In the first part of the curling movement (or until the dumbbell is raised to the point where it tends to fall inward out of the grasp) the hand should be bent upward and inward as far as possible. In lowering the bell also the wrist should be strongly flexed. Bending the wrist in this manner while curling is highly effective for the forearm muscles that flex and adduct the wrist.

In this "one arm curl with dumbbell, in reclining position," one should duly become able to handle from 50-60% more weight than in the usual one-arm curl in standing position. That is, if you can curl, say 50 pounds correctly in a standing one-arm dumbbell curl, in the reclining position you should be able to curl 75-80 pounds. But, of course, for exercise, use a weight that will permit you to repeat the movement from 8-12 times.

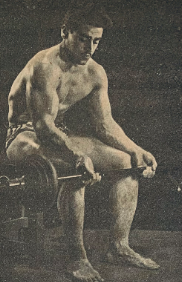

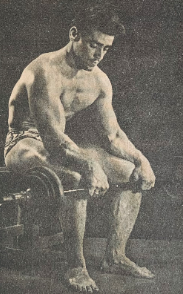

A direct exercise for the flexor muscles that act on the wrist, and one which has similar effects to the single-arm dumbbell curl just described, is to curl a barbell with the hands alone while in a sitting position, the backs of the forearms resting along the thighs and hands extending beyond the knees. This exercise is known as the "wrist curl."

First pick up the barbell using the "under-grip' (palms up), then take a sitting position on the edge of a chair, bench, or stool, with the forearms resting on the thighs as stated. The exercise consists in raising and lowering the barbell by wrist (hand) action alone. As the hands are lowered, relax your grip and let the bar roll down nearly to the ends of the fingers; then s the bar is raised, close your grip and bend the wrists upward as far as possible.

Note the bench height and hips below its level. Also, the heavy/light bars for super-setting from one to the other.

A greater bending of the wrists can be made if the bar is grasped rather wide apart. The amount of weight to be used in this exercise should be about 2/3 of what one uses in the regular two-arm standing curl.

The wrist curl can also be applied to the extensor muscles on the back of the forearms by grasping the barbell with the backs of the hands up. Otherwise perform this "reverse wrist curl" in the same manner as the regular wrist curl. Use, however, only a little more than 1/2 as much weight.

For this exercise procure a piece of round wood, 1.5 inches in diameter and about 2 feet in length. Midway between the ends of the rod bore a hole through from side to side. Run a piece of strong cord or light rope through the hole, and tie a large knot on the end to that it cannot slip through. To the other end of the cord attach a light weight (a 2.5 or 5 pound plate makes a convenient weight to start with). The cord should be of such length that after one end has been passed through the roller and knotted, and the other end tied to the weight, the arms can be raised straight in front nearly to shoulder-level before the weight leaves the ground.

Now, standing erect, hold the roller straight in front of you, backs of the hands upward, at the height of the shoulders, with the hands near the ends of the roller. Wind the weight up to the roller by twisting the top of the roller away from you, twisting first with one hand, then the other. Each time you twist the roller, the wrists will bend exactly in opposite directions.

After the weight has been rolled all the way up, without lowering your arms loosen your grip and let the weight unroll itself. Next, wind it up again, but this time twist the top of the roller towards you. Repeat once more the forward-rolling-up of the weight, once more the backward, and at least once more the forward.

Twisting the tip of the roller away from you develops the flexor muscles on the inside and inside-front of the forearm.

Twisting the top of the roller towards you develops the extensor muscles on the outside and outside-back of the forearm.

In this exercise, add a pound to the weight about every two months, maintaining the number of windings used at the start, that is, at least three winding forward and two backward.

Remember throughout the exercise to keep the body erect, the hands on the end of the roller, the arms straight at the elbows, and the roller horizontal (don't let it wobble). The object should be to wind the weight up in the fewest possible number of turns, bending the wrists to their fullest extent and thereby bringing the forearm muscles into complete contraction. If this is done, a more effective exercise for developing the forearms could hardly be devised.

A variation of the usual wrist roller exercise is to grasp the roller with the palms of the hands facing upward, otherwise performing the twistings in the same manner.

A third method is to wind with one palm up, the other down.

An interesting form of exercise for developing the forearm muscles that act on the wrist joint consists of "leverage" movements. By this term is meant exercise in which heavy resistance is furnished without using much actual weight. The principle is that the lifting of an object, where the weight is located at a considerable distance from the bodily joint involved, throws as much stress on that joint as does the lifting of a far heavier weight held closer.

Leverage exercises for the forearm and wrist can be performed very effectively with an ordinary adjustable plate dumbbell, by loading only one end and grasping the other end. The adductor muscles of the forearm may be exercised by grasping the dumbbell handle like a club and levering the loaded end up and down.

The abductor muscles may be similarly exercised by changing the grip on the dumbbell handle so that the thumb-side is nearest the end, the other (weighted end) now being behind the body. A heavier weight can be used in the latter exercise (for the abductor muscles) than in the first-described movement (for the adductor muscles).

Be sure to keep the elbow straight at the elbow in these two exercises; all the movement is done at the wrist-joint alone.

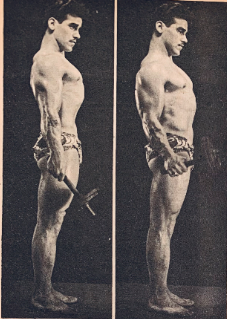

To exercise the muscles that pronate and supinate the hand, grasp the leverage dumbbell in the manner shown in the adjoining photographs illustrating the "wrist twister". The range of movement in these leverage exercises being short (and thereby covered quickly), the number of repetitions to be performed can with advantage be greater than usual, say, from 15 to 20 times.

Another application of the leverage principle for developing the forearms is to perform various wrist movements while grasping an ordinary high-backed "kitchen" chair. [These are sold on gym equipment websites, right?] Preferably, the cross-brace at the top of the chair-back (on which the handhold is taken) should be at least five inches in width. The chair need not be of heavy construction -- in fact a real light chair will afford better exercise -- as each movement should be repeated a number of times. These movements are so well depicted by the accompanying photographs that written description is unnecessary. Simply remember that in al these "chair" exercises the effort should be confined as far as possible to the wrists -- or, to be strictly correct, to those forearm muscles which act on the wrist. If you use all these chair exercises, there should be little need for the regular use of other "wrist" exercises.

The pupil who likes to experiment can doubtless work out still other leverage exercises with a chair. However, the wrist-roller lends itself better to a systematic increasing of the resistance employed, though with the chair exercises one can either fasten objects of increasing weight to the end of the chair or use heavier chairs.

It is now opportune to mention an exercise of a different nature. This is to perform the "floor dip" while supporting the body on the tips of the fingers and thumbs instead of on the flats of the hands as usual.

This exercise has the peculiar value of tending to offset the usual clutching movements of the fingers, and so to make them shapely and straight. The close together the fingers and thumb of each hand are placed on the floor, the more difficult and effective the exercise becomes. As you ability improves, the exercise should be made more effective by raising one or more fingers on each hand and pressing with the thumb and only one or two fingers. Before long, you should be able to perform the dipping movement while using your thumbs only. A few athletes have acquired the strength, balance, and joint-toughness to dip on only one thumb. The final degrees of difficulty come, however, when one can dip while using, first, only the two index fingers, and, ultimately, only the two middle fingers. These two latter feats denote extraordinary finger strength of this type, but they have been accomplished, notably by the famous hand-balancer, Robert L. Jones, of Philadelphia. Jones, incidentally, could perform, among a great many other feats, a phenomenal handstand on his thumbs only on a pair of fixed Indian Clubs.

So far, in these articles on arm development, I have prescribed exercises for the flexor, extensor, pronator, and supinator muscles of the upper arm and forearm, and for those forearm muscles which flex, extend, adduct, and abduct the hand (and to a certain extent, the fingers). Accordingly, there remain to be described only exercises for the "grip" -- the grasping muscles of the fingers and thumb.

It should be borne in mind that in following a program of general bodybuilding with weights, the hands, wrists, and arms incidentally receive a considerable amount of developing work. That is, the grasping and manipulating of the barbell in each and every exercise compels a certain degree of development in the fingers, hands, and wrists, no matter which part of the body the exercise is particularly intended for. In some exercises the "grip" is developed, and in others, where a fairly heavy barbell or dumbbell is held on the top of the palm (in position to raise overhead), the supporting strength of the wrist is improved. Thus, all this incidental work for the wrists and grip contributes to the development of the forearm and hand.

Exercises especially adapted for the development of unusual strength in the hand and fingers are largely of the nature of tests, stunts, or the specialties of noted strong-men. For this reason, such exercises will be presented in my next article, on famous men of arm strength, rather than dealt with here as regular body-building exercises.

Enjoy Your Lifting!

No comments:

Post a Comment