Wunnerful!

In an article in the October '95 IronMan, Richard Winett, Ph.D., commented, "Remember the fiasco of the early 1960s? Some equipment manufacturers sold thousands of 'isometric power racks' to a gullible public before this worthless concept was proven false."

The main reason isometrics fell from favor in the strength training community was the disclosure some years after the concept's introduction that those who had made fantastic gains on the isometric system were using steroids at the same time. When someone went on steroids, his lifts increased regardless of the type of training system he was used, so many people assume that the isometric program was just a smoke screen that allowed Bob Hoffman of the York Barbell Company to market thousands of power racks - and that isometrics were useless. It was a classic case of throwing the baby out with the bath water.

John Ziegler, M.D., is often credited with inventing functional isometrics, but this is not, strictly speaking, true. Ziegler was a prominent physician in the Washington, D.C., area, and he was fascinated with strength. He came across some research on the subject done at Springfield College in 1928, but the researchers didn't couple the method with a specific groups of exercises. In 1953 Dr. Mueller of Germany began conducting some experiments with isometrics, but they weren't relevant to strength athletes. Ziegler took the concepts and geared them specifically to Olympic weightlifters. Later, he did the same for bodybuilders.

The early results were most encouraging, but he needed a test subject. He selected Bill March for several reasons.

Note: In case you haven't read this yet, more details from Mr. March here:

https://ditillo2.blogspot.com/2017/09/isometrics-isotron-dr-john-ziegler.html

William "Bill" March was a lifter on the rise having just totaled 745 as a 181-pounder, and, most important, was willing to make the 180-mile round trip to Ziegler's base in Olney, Maryland, four or five times a week. His progress - and that of the second subject, Louis Reicke - was staggering in a time when gains came in five-pound increments per year, not 100-pound gains in six months.

People often forget that Ziegler wasn't the only one doing such testing. At Louisiana State University Dr. Barham put 175 subjects through an isometric program and found the average gain in strength to be 5% a week. Many scientists and physical educators wrote papers on the subject. All of their results were very positive: Isometrics would improve strength.

The merits of isometrics were zealously promoted by Bob Hoffman in Strength & Health magazine throughout the '60s. With Hoffman spreading the gospel and prominent researchers such as Dr. C.H. McCloy of Iowa State University and Dr. Arthur Steinhaus of George Williams College in Chicago supporting his claims, isometrics became part of every strength athlete's program until the late 1960. By then, however, the secret had leaked out. Steroids, not isometrics, were the reason the York lifters made such spectacular gains. The system slowly lost favor and eventually was put aside entirely.

The assumption that steroids were the primary factor in the strength gains was absolutely true. March and Riecke would not have gotten as strong had they only used isometrics. They would, however, have gotten a bit stronger with just the isometric exercise.

When the system first came out, hundreds of competitive weightlifters, strength athletes and even bodybuilders used it. They all benefited in terms of improved strength. None of these people used steroids. In fact, only two test subjects, March and Riecke, were using steroids. The rest of us were natural, but when we followed the program as outlined in the magazine and the course, we got stronger. A few did nothing but isometrics three or four times a week, then did squats and the Olympic lifts one day a week. Others preferred to mix the isometrics with their regular routines. Everyone got stronger. Some got a great deal stronger.

I was an Olympic lifter in Dallas at the time, and like everyone else in the Southwest I learned of isometrics from Riecke, for he came to all of the meets in Texas. The isometric training helped my Press somewhat, but it really improved my pulling power. Others had different results, making gains on the presses or squats but not so much on their pulls.

One thing we all discovered was that it took some practice to learn how to perform the isometrics correctly. It was simply a matter of pushing and pulling against a stationary bar. It required a great amount of focus and concentration, so several weeks passed before we got any results from our workouts. It was difficult to tell if we were, in fact, really exerting ourselves completely.

This is the main reason Ziegler quickly modified his program. He had March and Riecke move a weighted bar a short distance, then lock into an isometric hold for the required count. Those of us in the hinterlands, unfortunately, didn't learn of this adaptation for many years. It seems that Hoffman didn't want to revise his published course -

although he knew that the change would make it obsolete.

Winett is partially correct in his comment about equipment manufacturers selling thousands of power racks, but it wasn't a number of manufacturers, it was just one. The York Barbell Company sold all of the racks, and it sold a lot of them. Schools, colleges and YMCA gyms embraced the new system, for it was safe, fairly simple, and could be done quickly.

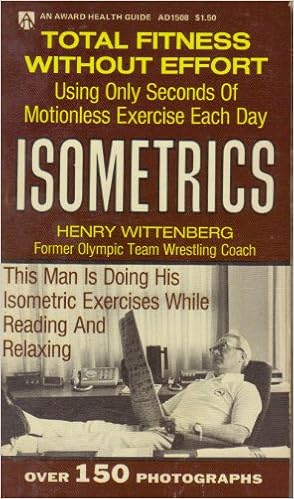

Note: A lot of people nowadays don't realize how big the isometric thing was in the 1960s.

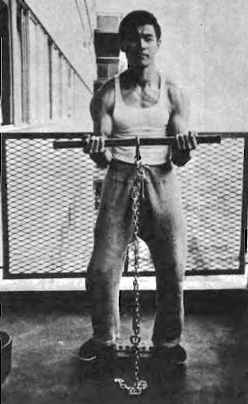

Bruce Lee demonstrating one of the "chain" versions of isometric exercise.

There were many companies and individuals selling the 'block and chain' device.

The Roberts "Portable Exerciser"

Wall chart from Mickey Mantle's "Minute a Day" pitch.

Bullworker!

The Iso-7X by Ontel had a "calibrated strength meter"

Weider's halfhearted entry into the market.

Good Grief.

Yes, music for isometric exercises!

But these should not be confused with the more valid isometric and isotonic/isometric (isometronic) forms of strength building that were developed for serious strength athletes. Some of the old ads, you gotta admit, are fun to get a look at. You get the idea here, I'm sure. Isometrics in the '60s was a saleable item! Just don't get all in a stinkin' huff thinking that Hoffman and York were the only lot that made some money with the idea.

York also put out a course specifically for football.

Not many people still have a copy of this one.

Not many people still have a copy of this one.

And here's a great article by Bud Charniga on the marketing of functional isometric contraction:

The real article will continue from here . . .

No, silly. From here . . .

After seeing Riecke add 65 pounds to his Press in four months, every gym in the Southwest put in a power rack. Very few of them, however, were purchased from York. Almost all of them were handmade. Southern Methodist University built 20 of them and installed them under the bleachers of Ownby Stadium.

The racks weren't hard to build. You just drilled holes in appropriate places in two 3 x 5 boards and inserted a metal pipe. When I was a counselor at a camp one summer in Branson, Missouri, I made a portable power rack out of chains and pipe (block and chain variety, see above) to carry on a boat trip down the Buffalo River. It worked fine until a running back from the University of Arkansas bent the pipes performing the high position in the squat.

Competitive athletes are very pragmatic people. If a program of nutritional supplement doesn't work, they dump it quickly. If a program or supplement does bring some results, they incorporate it into their routines. Lifters stayed with isometrics for a long, long time because the technique brought results.

Everyone who used isometrics benefited to some degree. Naturally, some liked the systam and took to it more readily than others. I made improvements but didn't really enjoy isometric training as much as I enjoyed lifting weights. An isometric workout just didn't leave me with that weary but wonderful feeling I got from a long, hard session with the barbell. I also found an aesthetic pleasure in doing snatches and clean & jerks that isometrics didn't provide for me. Others, though, preferred the quick, condensed form of isometrics.

One of the problems is that very few people actually understand how to do the exercises properly.

Unfortunately, there are probably only about two dozen people who know how to teach the system properly, and very few of them re actively involved in coaching or writing. The system has been nearly lost - but not quite.

The basic theory of isometrics is this: If you hold a maximum contraction of a muscle group to 8-12 seconds, you make that group stronger. Because the exercise is much less tiring than a conventional program of sets and reps, you can do it more often. It's much easier to recuperate from isometric contractions than from a half hour of weightlifting.

Though these concepts remain perfectly true, I have to believe that a training program of just isometric exercise will never become popular again. It's basically a boring way to train. Including one or two isometric movements in a routine, however, is another story.

I use isometrics with all my advanced athletes, as well as those who have glaring weak points. Done sensibly, isometrics can improve the bench press, squat, any pulling exercise and even movements designed for smaller muscle groups such as the triceps and biceps.

It is an excellent way to strengthen the weakest portion of any lift. If, for example, you have difficulty moving your bench press through the middle range, you can use isometric-isotonic exercise to remedy the problem. Set the bottom pins just below your sticking point and the top pins right at the sticking point. Space the pins so the bar will only move an inch or two, even less if possible.

Do 3 sets: 2 warmup sets to get the feel of the exercise and 1 work set. On the warmup sets just touch the bar to the top pins 3 times but don't try to hold the bar against them. On the work set push the bar against the top pins and lock it into position tightly for no less than a count of 8 and preferably a count of 12. If you can't hold it for 8, the weight is too heavy. If you can hold it for 12, the weight is too light.

Keep in mind that the amount of weight on the bar is less important than the amount of time you hold it locked into position. This move is called an isotonic-isometric exercise because you move the bar a bit before locking into an isometric hold.

If you decide to work just one position on any lift, do so after you've done your regular routine on that exercise, but don't do as much as you'd normally do. Drop the back-off sets or one of the work sets. Should you choose to do three positions in the rack - start, middle, and finish position - don't do your regular program at all. Instead, do 1 or 2 light warmup sets, then do the rack work. If you try to do both, you'll defeat your purpose.

Each time you do a position in the rack, try to increase the weight on the bar slightly. This is an ideal way to overload. It's very safe because you can do it alone, and it's extremely productive. Keep in mind that it will take a bit of practice to learn how to apply full exertion to the fixed barbell. Your second and third workouts will be much more productive than your first.

Isometrics can be used to strengthen any exercise. Squats and deadlifts are the obvious movements, but even smaller muscle groups respond favorably. Vern Weaver incorporated many isometric exercises into his bodybuilding routine and became one of the strongest Mr. Americas ever. He especially liked locking in a series of curling positions.

Isometrics are great for improving strength. They have to be balanced with your other training, however, because if you try to do your regular workout and then isometrics, you'll overtrain. Try

Try doing one position once a week for six weeks.

I think you'll be pleased with the results.

Added notes of a more bodybuilding nature from Steve Holman:

Isometrics: How to Use Them to Up Your Size and Strength

If you're not into setting up a power rack so you can pull or push against the pins as they did back in the '60s, you can still benefit from isometrics. Here are two ways to give your gains an isometric-style boost:

1) Isometric Stops.

This technique was popularized by Ray Mentzer, Mike's brother and the 1979 Mr. America. For these you do a regular set to positive failure, have your partner help you with a few forced reps, then have him raise the weight to the top position for negatives. Instead of lowering all the way down in one continuous motion, however, you stop the bar one-third of the way down, two-thirds of the way down, and close to the bottom. At each of these positions along the range of motion you drive hard, attempting to reverse the movement of the barbell, dumbbells, or whatever for 4 to 6 seconds. Your partner should prevent any upward movement by applying pressure to the bar, if necessary, in each position. This makes for a very intense set, and you may want to eliminate the forced reps prior to your isometric contractions to prevent over-training.

2) Isometric Finisher

This is probably the easiest way to use isometrics. Whenever you can't get another full rep, pull or push the weight as far as you can and drive hard for 4 to 6 seconds at the sticking point. That's all there is to it. This will force the target muscle to get stronger at the sticking point.

No, silly. From here . . .

After seeing Riecke add 65 pounds to his Press in four months, every gym in the Southwest put in a power rack. Very few of them, however, were purchased from York. Almost all of them were handmade. Southern Methodist University built 20 of them and installed them under the bleachers of Ownby Stadium.

The racks weren't hard to build. You just drilled holes in appropriate places in two 3 x 5 boards and inserted a metal pipe. When I was a counselor at a camp one summer in Branson, Missouri, I made a portable power rack out of chains and pipe (block and chain variety, see above) to carry on a boat trip down the Buffalo River. It worked fine until a running back from the University of Arkansas bent the pipes performing the high position in the squat.

Competitive athletes are very pragmatic people. If a program of nutritional supplement doesn't work, they dump it quickly. If a program or supplement does bring some results, they incorporate it into their routines. Lifters stayed with isometrics for a long, long time because the technique brought results.

Everyone who used isometrics benefited to some degree. Naturally, some liked the systam and took to it more readily than others. I made improvements but didn't really enjoy isometric training as much as I enjoyed lifting weights. An isometric workout just didn't leave me with that weary but wonderful feeling I got from a long, hard session with the barbell. I also found an aesthetic pleasure in doing snatches and clean & jerks that isometrics didn't provide for me. Others, though, preferred the quick, condensed form of isometrics.

One of the problems is that very few people actually understand how to do the exercises properly.

Unfortunately, there are probably only about two dozen people who know how to teach the system properly, and very few of them re actively involved in coaching or writing. The system has been nearly lost - but not quite.

The basic theory of isometrics is this: If you hold a maximum contraction of a muscle group to 8-12 seconds, you make that group stronger. Because the exercise is much less tiring than a conventional program of sets and reps, you can do it more often. It's much easier to recuperate from isometric contractions than from a half hour of weightlifting.

Though these concepts remain perfectly true, I have to believe that a training program of just isometric exercise will never become popular again. It's basically a boring way to train. Including one or two isometric movements in a routine, however, is another story.

I use isometrics with all my advanced athletes, as well as those who have glaring weak points. Done sensibly, isometrics can improve the bench press, squat, any pulling exercise and even movements designed for smaller muscle groups such as the triceps and biceps.

It is an excellent way to strengthen the weakest portion of any lift. If, for example, you have difficulty moving your bench press through the middle range, you can use isometric-isotonic exercise to remedy the problem. Set the bottom pins just below your sticking point and the top pins right at the sticking point. Space the pins so the bar will only move an inch or two, even less if possible.

Do 3 sets: 2 warmup sets to get the feel of the exercise and 1 work set. On the warmup sets just touch the bar to the top pins 3 times but don't try to hold the bar against them. On the work set push the bar against the top pins and lock it into position tightly for no less than a count of 8 and preferably a count of 12. If you can't hold it for 8, the weight is too heavy. If you can hold it for 12, the weight is too light.

Keep in mind that the amount of weight on the bar is less important than the amount of time you hold it locked into position. This move is called an isotonic-isometric exercise because you move the bar a bit before locking into an isometric hold.

If you decide to work just one position on any lift, do so after you've done your regular routine on that exercise, but don't do as much as you'd normally do. Drop the back-off sets or one of the work sets. Should you choose to do three positions in the rack - start, middle, and finish position - don't do your regular program at all. Instead, do 1 or 2 light warmup sets, then do the rack work. If you try to do both, you'll defeat your purpose.

Each time you do a position in the rack, try to increase the weight on the bar slightly. This is an ideal way to overload. It's very safe because you can do it alone, and it's extremely productive. Keep in mind that it will take a bit of practice to learn how to apply full exertion to the fixed barbell. Your second and third workouts will be much more productive than your first.

Isometrics can be used to strengthen any exercise. Squats and deadlifts are the obvious movements, but even smaller muscle groups respond favorably. Vern Weaver incorporated many isometric exercises into his bodybuilding routine and became one of the strongest Mr. Americas ever. He especially liked locking in a series of curling positions.

Isometrics are great for improving strength. They have to be balanced with your other training, however, because if you try to do your regular workout and then isometrics, you'll overtrain. Try

Try doing one position once a week for six weeks.

I think you'll be pleased with the results.

Added notes of a more bodybuilding nature from Steve Holman:

Isometrics: How to Use Them to Up Your Size and Strength

If you're not into setting up a power rack so you can pull or push against the pins as they did back in the '60s, you can still benefit from isometrics. Here are two ways to give your gains an isometric-style boost:

1) Isometric Stops.

This technique was popularized by Ray Mentzer, Mike's brother and the 1979 Mr. America. For these you do a regular set to positive failure, have your partner help you with a few forced reps, then have him raise the weight to the top position for negatives. Instead of lowering all the way down in one continuous motion, however, you stop the bar one-third of the way down, two-thirds of the way down, and close to the bottom. At each of these positions along the range of motion you drive hard, attempting to reverse the movement of the barbell, dumbbells, or whatever for 4 to 6 seconds. Your partner should prevent any upward movement by applying pressure to the bar, if necessary, in each position. This makes for a very intense set, and you may want to eliminate the forced reps prior to your isometric contractions to prevent over-training.

2) Isometric Finisher

This is probably the easiest way to use isometrics. Whenever you can't get another full rep, pull or push the weight as far as you can and drive hard for 4 to 6 seconds at the sticking point. That's all there is to it. This will force the target muscle to get stronger at the sticking point.

No comments:

Post a Comment