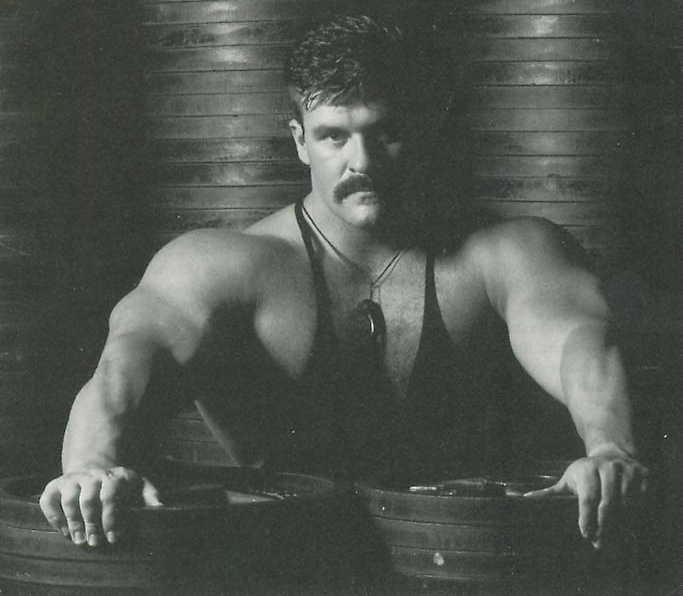

The Author, J.M. Blakely

Let's clear up one point right away:

Bench Pressing is an Attitude!

The first step to a big bench is your mental perspective.

What is heavy?

What isn't heavy?

These are the wrong questions. Nothing is heavy. But rather you are or are not strong enough. Quit thinking about the weight and concentrate on your strength. No bench program will work for anyone who is locked into thinking about the heft or the load or the burden; you must learn to think about and learn to trust your own power. My first point is this:

I believe your ATTITUDE affects your success more profoundly than your training.

I use a training protocol that helps generate a positive attitude and forces one to build confidence in one's own power. But not without risk. To build faith in oneself, one must continuously put oneself on the line! This leads to growth physically and psychologically with each success and offers excellent (albeit harsh) lessons with each mistake.

I take a lot of singles at or near max. I believe you must ask of your body and mind in training what you expect of them in competition. The risk is, of course, over-training. But that is minimized by the simplicity of the program. However, I use joint soreness as a rule. Muscular soreness is trained through but pain around the joints is a marker for backing off.

As an athlete matures, he learns to become very tuned into his body and aware athletes know how far they can go. Pay attention to your body. With that in mind . . .

My second point is to always ask the best from yourself and prove it by putting yourself on the line - frequently. As you succeed you will gain confidence and then when you fail you will become aware of weak points you need to work on that you might only normally learn at a meet.

My third point is SIMPLICITY. Keep your program simple. Complex programs are wrought with pitfalls and drain the focus. Do only those things that help most. Concentrate your energies on doing few tasks well, rather than many tasks poorly.

My fourth point goes hand in hand with the above and it is INTENSITY. Intensity has more to do with trying better. Intensity is learning to give all your effort in a relatively short burst. Intensity has nothing to do with long grueling workouts or exhausting lists of exercises that slowly fatigue you until you finally just run out of energy, time, or attention span. Intensity is forcing yourself to bring up all your concentration, all your effort, all your strength, and in fact, all you have into one single point of execution. Truly you must agree that one can only sustain a few of these per workout.

I respect lifters in full meets who must survive one or two such efforts in each of the three lifts every outing. If you learn to give this type of effort you will soon find your workouts becoming shorter and consisting of fewer movements. I contend that you can do two exercises per body part; if you feel you can do more you have saved yourself to do that. It really is a learned discipline to be able to give it all and hold nothing back. Yet that is exactly what is demanded at the meet, so train accordingly.

My fifth point is to REMEMBER what it's all about.

It's about progress. There is no substitute for progress.

Progress is the only indicator of a program's value. Progress is the only point. No amount of soreness or fatigue or grunting or burning or sets or reps means anything. Once can pile up workout after workout that is exhausting or causes great soreness or does whatever else one might think constitutes a great workout . . . and still show no progress.

I've seen trainees get a whole year of "great" workouts and have nothing to show for it but frustration and their fond memories of how fatigued and sore they were. Don't let yourself believe for a minute that anyone cares how hard you worked or how great your workouts were. And neither should you.

You should judge your workouts and program by the only fair ruler that matters . . .

PROGRESS!

If you are not improving, then there is no excuse you can give me for your program. Only one thing matters - getting stronger and stronger each and every workout. I want to emphasize that you must expect progress every workout. If you show no progress from one workout to the next, then why should you expect any improvement after a two month string of such workouts? Or four months Or six months? Keep accurate records and make no exceptions.

Demand progress from yourself.

The Program

This program is based on the above tenets. Following simplicity, there are just two exercises. One pressing movement that stresses the pectoralis and anterior deltoids, and one triceps movement that concentrates on lockout strength. There should be no more than two exercises per body part.

Following intensity, you must learn to pack all of your effort into those two movements. If you can do three exercises in one workout, you have not yet learned to completely extend yourself.

Following specificity (which is the law that states that the body adapts to the exact demands placed upon it), the main pressing movement should always be the bench press in exact competition form. The majority of your time and energy should be placed here. Master the skill of benching. Nothing is more specific to benching than the movement itself, Norbert. Incline benching is a fine exercise and will strengthen the pressing group of muscles, but it is not 100% transferable to flat bench. With the flat bench there is no loss because there is no transfer, as you are practicing the exact skill and that is 100% applicable.

Simply stated, to get better at benching, you must bench!

A second exercise should accentuate the elbow joint but not completely isolate it. The goal is to learn to use the muscles together in concert to achieve an additive or even synergistic effect. Train them that way. I suggest a narrow grip bench press with elbows out to the sides, no wider than 45 degrees from the lats. Try to emphasize less shoulder involvement and focus on the lockout. The move should accelerate gradually and pec drive also should be under-emphasized. Peak power should occur from just below the sticking point through lockout.

In addition, I RECOMMEND NO SHOULDER WORK. Not on this day or any other. It is too easy to overtrain this muscle group because of the intensity and because of the mechanics of pressing. If you need shoulder work, do it in the off season along with general conditioning and strengthening. But in season save your power for what will help you most.

The set and rep scheme is as follows:

Warm up as needed but don't fatigue yourself. The idea is to get prepared and not to get tired. Establish a warmup pattern. This pattern should be repeated every workout as well as in competition.

Example:

135x10, 225x10, 315x6, 465x3, 480x1.

At this point you should take several near max single singles:

465x1, 480x1

and on occasion a max attempt, or if training is going well, a supra max attempt

505x1.

DO take frequent near maxes; DO NOT take lots of true maxes.

Also, one other note concerning the warm up that is especially true at meets: Use poundages that require only 45s and 25s. Don't waste time and energy tallying up odd bar loads and hunting for small denomination plates. You have enough to worry about and don't need the trouble. You should be able to go through your warmup, at a meet or in training, on autopilot. KEEP IT SIMPLE!

That is the actual skill practice portion of the workout. It is like practicing a meet each workout. You will feel totally prepared by the time the real meet rolls around. But while this will improve your bench skills, there is still a need for strengthening.

And for that I can think of nothing better than pause reps.

Pause reps build isometric strength at the bottom which adds to your control and stability. Pause reps also ensure that you are building power at the onset of the press by eliminating bounce, heave, and muscle stretch reflex. Thus, all the power must be muscle-generated. Finally, this is what you are required to do under meet conditions and there is no better way to build central drive (motor cortex nerve recruitment in the brain).

Farther from the meet, say more than six to eight weeks, I suggest 4 sets of 6 reps with a one second pause. Closer to the meet, switch to triples with just a bit longer pause (1.5 seconds).

For the TRICEPS EXERCISE, only a brief warmup is needed (2 sets) and right to the work.

Follow the same pattern (4s6 or 4x3) but without the pause. However, this is not to say that the bar should be allowed to bounce or behave uncontrolled at any time. My rule of thumb is simply that the bar should come down slower than it comes up. DOWN SLOW, UP FAST.

And that is it! 4x6 pause out from the meet (for as many weeks as 6 or 8) and 4x3 at 6 weeks in.

Off season should be about 8 weeks. During this time STAY AWAY FROM THE BENCH. Use this period to develop weak areas. Do general body building movements and hit the rotator cuff muscles. Give the bench a break.

One final point:

Use your shirt on your near max attempts beginning no later than 6 weeks out. You must practice this skill. I will say it again: PRACTICE singles in your shirt well prior to meet day. I would say it again because so many make this mistake but that would be doubly redundant. To prepare properly this can not be overlooked.

This is the exact program I used to go from 400 to 500 and from 500 to 600. It was also the mainstay of my attack on 700. It has never failed to help others.

If you try the program try it without alteration. Use it just as outlined. If you feel you need to modify it of course you can to suit your needs, but the program is so basic that it will only tolerate slight modification without becoming a totally foreign entity. Keep in mind that it may be you that needs the modification, not the program. Try it without aberrance. Then if you still feel it necessary, modify it to your taste, but try to keep its context intact.

I realize there is more than one way to skin a cat.

GOOD LUCK!

No comments:

Post a Comment