For decades, Clarence Bass (born 1937) has been photographed in bodybuilding poses that trace his transformation from an embryonic weightlifter of 15 to a ripped septuagenarian. The pictures represent a biological time line of how little the human body declines with proper care and feeding. His latest photographs, taken a little shy of his 70th birthday, reveal a man virtually bereft of body fat. He is not so much a portrait of strength, though he is that; he is a model of muscle definition. Everything seems to pop. Tendons and veins rise up out of his skin like tightly drawn cables. He has abs to die for.

"For all the softies of the world," said photographer Laszlo Bencze, who photographed Bass, "the only thing they desire is defined abs. And Clarence has got that in spades."

Outside the hypercritical eye of the bodybuilding establishment, where no imperfection goes unnoticed, Bass's physique has changed little since 1978 when he won his height class at the Past-40 Mr. America competition. The similarity between age 40 and 70 is ll the more remarkable because Bass than was using anabolic steroids.

Now, instead of drugs, he uses a few over0the-counter nutritional supplements. He lifts weights twice a week, mixes in another two days of short bouts of heart-pounding aerobics, takes lots of walks, and eats a near-vegetarian diet. He is not a slave to the gym. And when I spent a day with him in December 2007, we ate all day long.

America's health clubs are filled with barbell-lifting baby boomers intent on staying young forever. But will they, over decades, have the discipline, diet, and passion for weight training that Bass had demonstrated? Will any of them ever look as lean and strong?

"I don't think that you will ever see many people like Clarence Bass," said Terry Todd, a professor of exercise history at the University of Texas. "Clarence is very unique."

I learned about Bass when I came across his photographs in Physical Dimensions of Aging (1995), by Waneen W. Spirduso, a professor of kinesiology and public health, also at the University of Texas.

http://www.amazon.com/Physical-Dimensions-Aging-Waneen-Spirduso/dp/0736033157

Table of Contents:

http://catdir.loc.gov/catdir/toc/ecip0420/2004016531.html

Spirduso used pictures of Bass to make a point: Strength and muscular endurance decline mostly because of a lack of exercise - not because of factors associated with getting old. "One of the clearest findings in the literature on strength and aging is that disuse accelerates aging," she wrote.

For many years, much of the medical community failed to see the benefits of resistance training. "You really had to be there to see how people felt," said Todd, a former national champion powerlifter who weighed more than 300 pounds. He remembers meeting Kenneth Cooper, the physician and author of the 1968 book, Aerobics. At the time, Cooper saw little benefit in strenuous weight training. But with new research, attitudes began to change. A 1998 study by the American College of Medicine analyzed 250 research projects; among the findings, it found that strength training can make men and women stronger as they grow older, improve bone health, and help control weight. In one of the studies, older men and women were found to achieve greater gains in strength than younger people. Spirduso described elite elderly athletes as having a psyche in which the "body and functioning are very important components of self-awareness and self-esteem."

When I first saw the photographs of Bass, I was impressed with how strong he looked. But his muscularity, at his age, seemed excessive. I thought about TV muscleman Jack LaLanne and the infomercials featuring impossibly strong men and women hawking the latest exercise device. Mind you, this was early in my research, and I hadn't yet studied anyone as muscular as Bass. I didn't fully understand the passion, pride, and ambition that drove the older athlete; I hadn't come around to the notion that if a 70-year old man can spring 100 meters or run a marathon, why couldn't he try seeking physical perfection?

"I think the primary reason people are uncomfortable about these sorts of muscle poses, and to some degree this is true, is that vanity and ego are on such public display," Todd told me. He is co-director of Texas's Todd-McLean Physical Culture Collection, the largest archive in the world devoted to fitness, weightlifting, and exercise.

Bass's experimentation with steroids must be viewed in the context of the times. The International Olympic Committee added steroids to its list of banned substances for the 1976 Olympics in Montreal, but there was no testing for the presence of the drugs at bodybuilding competitions. It was certainly off the radar screen of professional sports and the public mindset. In Ripped, Bass laid it out in the open. While he did not condemn those who used steroids, he concluded that even though he used them for a short time, they were a disaster on his body.

There are no known long-term effects of steroids because no studies have been done, according to Charles Yesalis, professor emeritus of health policy and administration at Pennsylvania University and a leading expert on drug use in sports. "There has always been a vanity to man, but it clearly accelerating," Yesalis said. "I think that performance-enhancing drugs are just one piece of the puzzle." Athletes use them to gain an edge, but there is also the human desire to look better. The use of makeup, tanning beds, cosmetic surgery, even exercise, all figure into this yearning for achievement, he said.

In 1978 for the Past-40 Mr. America, Bass had subsisted on a low-carbohydrate diet; in the weeks before the competition, he was eating 18 eggs a day. His hands trembled from overtraining. The diet, his training, and probably the steroids produced emotional highs and lows that he called his Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde personality. With steroids, "in short, your body's hormone-producing mechanism gets lazy," he wrote. "Thus a real problem arises when you stop taking steroids."

As Bass was getting ready for his second over-40 competition without the aid of steroids, his bodyfat had zoomed from 2.4 to 9.1 percent. While still far leaner than the average man his age, he had six months to rid his body of unwanted fat.

Bass changed his exercise routine from mega-lifting sessions to shorter, high-intensity workouts that trained different muscles on different days. Each muscle group got four days of rest. He also reverted to a diet that leaned heavily on low-fat protein whole grains, fruits, and vegetables. Without using steroids, he was able to increase his strength and reduce body fat. Bass has essentially stayed with the same whole-foods diet and workout regimen ever since.

"If you are going to be a lifetime trainer," he told me, "steroids are absolutely the wrong thing to do. You're just jerking yourself around." Bass also is not a proponent of two other potential aids for older athletes: supplements for alleviating declining testosterone levels or hormone-replacement therapy. He believes a good diet and exercise trump supplements' purported benefits without risking potential consequences.

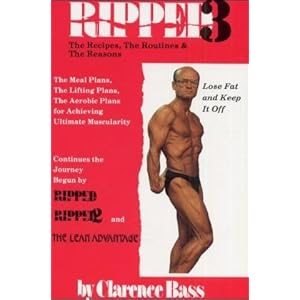

Bass practiced law until he was 57. But as his interest in health grew, he went into the fitness business full time with his wife, Carol. He has written ten and self-published nine books; his latest [as of the date of this article] is Great Expectations: Health, Fitness, Leanness Without Suffering, which was released in 2007.

I learned about Bass when I came across his photographs in Physical Dimensions of Aging (1995), by Waneen W. Spirduso, a professor of kinesiology and public health, also at the University of Texas.

http://www.amazon.com/Physical-Dimensions-Aging-Waneen-Spirduso/dp/0736033157

Table of Contents:

http://catdir.loc.gov/catdir/toc/ecip0420/2004016531.html

Spirduso used pictures of Bass to make a point: Strength and muscular endurance decline mostly because of a lack of exercise - not because of factors associated with getting old. "One of the clearest findings in the literature on strength and aging is that disuse accelerates aging," she wrote.

For many years, much of the medical community failed to see the benefits of resistance training. "You really had to be there to see how people felt," said Todd, a former national champion powerlifter who weighed more than 300 pounds. He remembers meeting Kenneth Cooper, the physician and author of the 1968 book, Aerobics. At the time, Cooper saw little benefit in strenuous weight training. But with new research, attitudes began to change. A 1998 study by the American College of Medicine analyzed 250 research projects; among the findings, it found that strength training can make men and women stronger as they grow older, improve bone health, and help control weight. In one of the studies, older men and women were found to achieve greater gains in strength than younger people. Spirduso described elite elderly athletes as having a psyche in which the "body and functioning are very important components of self-awareness and self-esteem."

When I first saw the photographs of Bass, I was impressed with how strong he looked. But his muscularity, at his age, seemed excessive. I thought about TV muscleman Jack LaLanne and the infomercials featuring impossibly strong men and women hawking the latest exercise device. Mind you, this was early in my research, and I hadn't yet studied anyone as muscular as Bass. I didn't fully understand the passion, pride, and ambition that drove the older athlete; I hadn't come around to the notion that if a 70-year old man can spring 100 meters or run a marathon, why couldn't he try seeking physical perfection?

"I think the primary reason people are uncomfortable about these sorts of muscle poses, and to some degree this is true, is that vanity and ego are on such public display," Todd told me. He is co-director of Texas's Todd-McLean Physical Culture Collection, the largest archive in the world devoted to fitness, weightlifting, and exercise.

Todd described Bass as "sort of a poster child" for the older superfit and he planned on using photos depicting "the changelessness of Clarence's body" when the collection became the centerpiece of the university's new 27,000-square-foot Lutcher Stark Center for Physical Culture and Sports.

Muscularity can be intimidating, even when it's someone who qualifies for Social Security. "It's sort of like, 'What have you spent the last 30 years of your life doing? Well, not much," Bencze said. "And so that makes them feel guilty. And if you feel guilty, you are going to be angry."

His Body of Work

In street clothes, Bass is lean and wiry. He is not tall - 5'6". His skin is remarkably smooth, and in certain light he appears 20 years younger. Bass is fond of sharing his views and, in fact, much of his time is now spent communicating his ideas on fitness. But it is with restraint - and not gimmicks. "He talks very softly but very strongly," said his old friend, Carl Miller, a former U.S. Olympic weightlifting coach.

The Sport of Olympic-Style Weightlifting, Training for the Connoisseur -

Carl Miller, 2011:

"How I look is very important to me," Bass said when we first met at his home in Albuquerque, New Mexico. "That's my proof, so to speak." Photographs are the "most visible way I can show that I have maintained this level of fitness," he said. "I realize that it is a turnoff for some people who are not into bodybuilding. But one of the things that distinguishes me from almost any other bodybuilder is this continuing documentation."

Muscle definition is influenced chiefly by muscle size and level of body fat. Every Saturday morning before breakfast, Bass goes into the bathroom and steps on a scale that measures his weight and body bar. He records the changes in his neat handwriting on a legal pad, the numbers fluctuating by a pound and a tenth of a percentage point, respectively. He has tested his body this way since 1977. In the days before high-tech scales, Bass was dunked underwater in a laboratory by researchers at the Lovelace Foundation for Medical Education and Research in Albuquerque.

In his most recent photographs, Bass weighed 150 pounds. His body fat registered 3.5% on his at-home scale - lower than that of most elite marathon runners. A more qualitative analysis occurs every morning when he gets out of bed and looks in the mirror at his nude body. "In terms of overall muscle mass, there are some posies that I used to be able to do that I can't now," he said. "But I am pretty proud of how I look."

Bass began lifting weights at 13, turning an old shed at home into his personal gym. As a junior in high school, he was New Mexico's state pentathlon champion - an event that combined push-ups, chin-ups, vertical jump, a 300-yard shuttle run, and an event called the bar vault, in which competitors pulled themselves over a high bar. As a senior, he finished second in the state wrestling tournament. In college, he began competing in Olympic-style lifts, which require great quickness and strength. Then he took up bodybuilding.

The year after he won his weight class in the Past-40 Mr. America, Bass, at 41, took first place in his class in another competition - the Past-40 Mr. USA. Overall, he won best abdominals, best legs, and most muscular. He was in the best condition of his life.

Then he stopped competing and I wondered why he suddenly quit. "I might lose," he told me as we sat in his kitchen. "I really had nothing to gain and everything to lose. I developed my reputation with these photos, and these contests aren't a lot of fun."

Bass was practicing law full time. He was also writing a column for Muscle and Fitness magazine. The next goal was to leverage his credentials and write more expansively about weight training and bodybuilding. A year after leaving the posing stage, Bass wrote his first book, Ripped: The Sensible Way to Achieve Ultimate Muscularity, which he self-published in 1980. The book delved not only into his diet and training philosophies but also discussed his use of steroids. Ripped has sold about 55,000 copies.

Bass's experimentation with steroids must be viewed in the context of the times. The International Olympic Committee added steroids to its list of banned substances for the 1976 Olympics in Montreal, but there was no testing for the presence of the drugs at bodybuilding competitions. It was certainly off the radar screen of professional sports and the public mindset. In Ripped, Bass laid it out in the open. While he did not condemn those who used steroids, he concluded that even though he used them for a short time, they were a disaster on his body.

There are no known long-term effects of steroids because no studies have been done, according to Charles Yesalis, professor emeritus of health policy and administration at Pennsylvania University and a leading expert on drug use in sports. "There has always been a vanity to man, but it clearly accelerating," Yesalis said. "I think that performance-enhancing drugs are just one piece of the puzzle." Athletes use them to gain an edge, but there is also the human desire to look better. The use of makeup, tanning beds, cosmetic surgery, even exercise, all figure into this yearning for achievement, he said.

In 1978 for the Past-40 Mr. America, Bass had subsisted on a low-carbohydrate diet; in the weeks before the competition, he was eating 18 eggs a day. His hands trembled from overtraining. The diet, his training, and probably the steroids produced emotional highs and lows that he called his Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde personality. With steroids, "in short, your body's hormone-producing mechanism gets lazy," he wrote. "Thus a real problem arises when you stop taking steroids."

As Bass was getting ready for his second over-40 competition without the aid of steroids, his bodyfat had zoomed from 2.4 to 9.1 percent. While still far leaner than the average man his age, he had six months to rid his body of unwanted fat.

Bass changed his exercise routine from mega-lifting sessions to shorter, high-intensity workouts that trained different muscles on different days. Each muscle group got four days of rest. He also reverted to a diet that leaned heavily on low-fat protein whole grains, fruits, and vegetables. Without using steroids, he was able to increase his strength and reduce body fat. Bass has essentially stayed with the same whole-foods diet and workout regimen ever since.

"If you are going to be a lifetime trainer," he told me, "steroids are absolutely the wrong thing to do. You're just jerking yourself around." Bass also is not a proponent of two other potential aids for older athletes: supplements for alleviating declining testosterone levels or hormone-replacement therapy. He believes a good diet and exercise trump supplements' purported benefits without risking potential consequences.

Bass practiced law until he was 57. But as his interest in health grew, he went into the fitness business full time with his wife, Carol. He has written ten and self-published nine books; his latest [as of the date of this article] is Great Expectations: Health, Fitness, Leanness Without Suffering, which was released in 2007.

The couple has also produced five audiotapes and three DVDs. Their business, Ripped Enterprises, sells other produces, including nutritional supplements. But unlike many fitness gurus, Bass does not tout supplements as the cornerstone of good health.

"The only defect with Clarence is that what he recommends isn't exotic enough," said Bencze, who in six months lost 20 pounds using Bass's whole-foods approach. With a good diet and exercise, Bass believes a person who wants to lose weight should try dropping no more than a half-pound (0.2 kg) per week. "It's so normal, so un-weird that many people think it can't work," Bencze said.

Eating to Stay Lean

Bass rarely leaves Albuquerque and prefers to spend much of his time at his two-story stucco home where he answers letters and emails from customers and writes on the topics of health, diet, and exercise for his website.

I had been driven from my hotel to the couple's home by Carol, who was then 64 and whom he calls "the enabler." Warm and outgoing, she works from home in the morning and heads to the office in the afternoon mailing out products and handling administrative matters. She went back to college in her 60s, changed her major from biology to English, and edits her husband's writing. The couple has a son, Matt, in his mid-30s.

Said Terry Todd, "He would have probably made an ideal monk in the Middle Ages, up in a monastery on the hills of Greece, if he could have sneaked Carol in the back door."

Staying close to home also allows Bass to better control the foods he eats. He is not a calorie counter, per se, but he has followed the subject so long that he knows the caloric value of nearly everything that goes into his mouth. He avoids food that contains concentrated calories, such as sugar and butter. He rarely eats red meat but also believes that a good diet is one that never calls for going hungry and allows for an occasional indulgence.

For breakfast, he scooped one cup of a mix of cooked oat groats, hulled barley, rye, spelt, kamut [Khorasan wheat], and amaranth into a bowl and added two tablespoons of ground flax and a handful of frozen fruit. Then he poured in another handful of frozen corn, peas, and green beans and a cup of plain soy milk. Bass drinks both nonfat cow's milk and soy milk. But he likes soy milk because it has the fattier "mouth feel" of whole milk with fewer calories. He also prefers to use the sweetener Splenda, or sucralose, which cuts calories by reformulating the properties of cane sugar. He cooked the contents in the microwave.

He placed a huge bowl of food in front of me that looked absolutely awful. I love vegetables, but not in my cereal, and I am not sure I had ever tasted soy milk. On the table in front of me was a teaspoon. I was to eat this prodigious concoction not with a tablespoon but with a teaspoon. The idea was to slow down my consumption so I didn't eat past the point of feeling full. There was, however, an implicit understanding that I should finish the whole bowl. The breakfast turned out to be surprisingly good - nutty, sweet, and almost buttery. The grains gave it some heft and the fruit and vegetables went well together.

Later in the morning he offered me an apple. Bass often has an apple and a quarter-cup of salmon as a mid-morning snack to keep his blood sugar at a high level.

Before lunch we walked on a patchwork of trails on the eastern edge of Albuquerque that threaded through public land a few blocks from his home. Sometimes he and Carol will walk farther into the Sandia Mountains. Bass has timed himself getting to the top. He told me that he knocked 10 minutes off the climb when he began taking the supplement creatine, which supplies energy to muscles. He also takes a multivitamin and vitamins C and E. But this was a recovery day and we walked leisurely through a moonscape flecked with withering grasses and cacti. On our return, the trail provided a sweeping vista of the city and the Rio Grande Valley.

"Most people think that aerobic exercise is boring," he said. "Well, the way most people do it, it is boring - going to gyms and reading newspapers. If you do it right, if you have a nice place to walk, you get revitalized."

When we came back, Bass served lunch: special peanut butter formulated with eggs and flax-seed oil on toasted whole grain break, a handful of carrots, and a large mug with equal portions of plain low-fat yogurt and plain soy milk. I was again handed a teaspoon. Bass quartered the sandwich for the same reason. "These are kind of mechanical ways to slow you down," he said.

By mid-afternoon, we were driving to his office in his Mercedes E55, and as I was eating a Tiger's Milk nutrition bar he had handed me, he gently admonished, "Eat slow."

Clarence and Carol often eat large salads, bread, and fish, chicken or eggs for dinner. But that night we went to a restaurant that served traditional New Mexican cuisine. Carol, who is as lean as Clarence, ordered a large burrito, without cheese, and ate it all. Bass slowly polished off a plate of huevos rancheros, sunny side up, and he shared a plate of Navajo fry bread with us. The two of them shared a Mexican flan (custard that is drizzled with caramel sauce). Bass did not have any alcohol, although he occasionally will have a glass of wine. He is abstemious because "alcohol weakens the control I usually have over my appetite," he wrote in one of his books, The Lean Advantage. "It seems to anesthetize my stomach and encourage me to go on eating beyond the point where I would normally be full and satisfied."

The Lean Advantage, Volumes 1, 2 and 3:

http://www.cbass.com/PROD02.HTM

For a snack at night, Bass has a slice of toast with almond butter, honey, and Benecol, a product intended to lower dietary cholesterol. He quarters the toast and eats a section every 15 minutes.

Bass felt he needed to drop 4 or 5 pounds and knock down his body fat by a few percentage points before he posed for his photos at 70. Six months before the shoot, he had preliminary photos taken. "I didn't like them," he said. "I had some extra weight around my love handles and lower back - pretty much everybody has it." He cut down by backing off slightly at every meal: a little less cooked grain and flax seed at breakfast, smaller amounts of peanut butter, and one fewer slice of bread at dinner.

Ripped Enterprises is located in a one-story office building that housed his legal practice before Bass went into the health business full tie. Two of the rooms are jammed with an array of weight machines, free weights, and other equipment positioned atop aging gold carpeting. The walls are covered with mirrors and pictures of bodybuilders. One room is devoted to lower-body exercises; the other, is for the upper body. There are plates, benches, cables, dumbbells, barbells, and a pair of weightlifting shoes. Each room contains impeccably maintained metallic blue Nautilus equipment from the 1970s that Bass bought from Arthur Jones, the founder of the company. Bass was so jazzed by the technology of pulleys and cams when it first came out that he and Carol flew to Florida to meet Jones.

He keeps additional equipment at home: In a room next to the garage, he has a Concept 2 rowing machine, a stair stepper, a Schwinn Airdyne, and a Lifecycle. In his garage an entire bay is outfitted with a squat rack, old-fashioned kettlebells [yes, it wasn't that long ago they were referred to as old fashioned!], weight-resistance machines powered by an air compressor, and a contraption called a glute-ham developer [again, 'contraption - not that long ago].

Bass had a heavy weight-training session the day before, his biggest of the week, so I didn't expect a big demonstration when we arrived at his office. But when I asked about his favorite lifts to keep his abs so buff, he knelt down in front of a machine with a cable and pulley. He pulled down on the weight and let his oblique muscles do the work. At the bottom of the pull, he slowly raised the weight - again relying on his abdominal muscles. The exercise is often practiced with the subtlety of a pile driver. With Bass, it was almost sensual - an embrace between man and machine.

"Clarence can't wait for the next workout," said Carl Miller, who owns a gym in Santa Fe. The key to lifting weights over many years "is that it has to capture your imagination so that you keep looking for ways to get better," Miller said. "You are always looking for a new training technique."

Bass has picked up and discarded an array of exercises and lifts over the years. At 60, for example, after more than a 30-year absence, he began incorporating technically more difficult lifts such as the power clean, power snatch, and squat snatch, which require quickness, strength, and good balance.

Bass exercises six or seven days a week, but he lifts weight only two of those days. He sits down with his workout diary before each session and plans what he will do. His diaries are 500 pages apiece and he's accumulated dozens of them over the years. Over time he has added more aerobic training for his cardio-respiratory system as well. On periodic visits to the Cooper Aerobics Center in Dallas, his fitness was judged by tests on a treadmill or stationary bicycle consistently put him in the top category for his age.

Bass is a disciple of the HIT (high-intensity training) school of weight training. Early proponents included Arthur Jones (the Nautilus founder) and former world-champion bodybuilder Mike Mentzer. Advocates of HIT believe the best way to build muscle mass is with short, infrequent, but very hard workout sessions rather than hours of exercise almost every day.

Typically on Sundays, he will work his entire body with weights, making more than a dozen lifts that push him to the upper end of his capabilities. After warming up, he will do only one heavy set or each lift - 8 to 15 repetitions. "The key point is that I do not wear myself out before I get to the set that really counts," he told me.

Three days later, he lifts weights with his upper body and then climbs on a Lifecycle, a computerized stationary bike for 20 minutes and pedals hard at various resistance levels. By constantly changing the intervals and intensity, he is mimicking what he believes is humans' ancient need to exert short bursts of energy.

Three days later he does crunches and works sundry core muscles. He also does about 20 minutes of hard pedaling on his Aerodyne, which requires pedaling and back-and-forth arm action. On other days he goes on walks for 30 or 40 minutes.

Bass has pushed back the hands of the aging clock because of his triad of diet, aerobic exercise, and weightlifting. His metabolism burns calories as if he were a youngster because he continues to stay almost as active as one. Strong, exercised muscles, even when they are resting, burn more calories than less-trained muscles. "Anyone wanting to lose or control weight should, in addition to eating less and exercising more, try to increase lean muscle mass," writes physician Andrew Weil in his book, Healthy Aging: A Lifelong Guide to Your Well-Being. Weight training, he said, will "keep the metabolic furnace burning bright."

I asked Bass about whether he ever thought of cutting back. What is the difference, I asked, between him and a 70-year old man in excellent health who walks a little and putters in the yard?

"One thing he isn't trying to do is challenge or improve himself," Bass said. "It sounds like he's an old man, and that doesn't excite me. I think you have to find something that excites you, that motivates you, so you want to get out of the bed and get down to the gym."

Aging is Inevitable

But Bass isn't bulletproof. There is the osteoarthritis in his lower back that has forced him to give up the use of his Concept2 rowing machine and traditional squats. He also has a weakness in his left shoulder and mild atrophy in his left triceps. On a visit to the Cooper Clinic, doctors discovered a buildup of calcium in his left anterior descending artery that requires the use of a statin drug to reduce cholesterol.

At 67, Bass also found that he was retaining excessive amounts of urine in his bladder. After several tests, he had surgery to remove abnormal lobes where urine drains from the bladder through the prostate.

"The whole situation went against my experience so far and my optimistic view of the future," he wrote in Great Expectations. "I expected a few problems to come with aging, but frankly I didn't expect this so soon. I went to the doctor with what I considered a minor problem - and I ended up in surgery."

When he first met his urologist, the doctor had concluded that Bass would have to insert a device into his penis three or four times a day to keep the urinary pathway open. It seemed barbaric. Bass responded with understandable reluctance; later, after it was clear he would have to do something, Bass countered with using the device less. He has been able to pare down the number of sessions to once a week, with his doctor's blessing.

Then, at 68, Bass had his right hip replaced. Neither Bass nor his doctors know why he needed the surgery, although hip replacements are the second-most common orthopedic surgery after knee replacements for people 65 to 84, according to a 2007 study by the federal Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Fifty years of weight training might have been the cause. Bass knows his share of old weightlifters who have had a hip replacement and who usually trace it back to an injury. "But I don't think that I would have gotten this far had I not been exercising," he said.

Rather than undergo a traditional hip replacement, he learned about an alternative procedure that causes less tissue damage because the hip is replaced through natural breaks in the muscle. His recovery was faster, although it left him with weakness in his hip flexor and numbness in his upper thigh. I noticed when we went for a walk, he moved stiffly at the beginning.

Bass talked to me matter-of-factly about his ritual of keeping his urinary pathway open. The practice changed from dread to just another regimen in his life. He checked with knowledgeable friends and did his own research to find a better procedure for his hip replacement that was more fitting for his active lifestyle - even though it meant a trip to Houston for surgery. He has dropped some exercises that cause problems for his body and added new ones. To get around weaknesses such as his osteoarthritis, he showed me how he clasped a belt around his waist that was attached to a biceps curl bar with weights (hip belt squat). This way he could still do a squat and work his leg muscles while keeping pressure off his spine.

"One of the raps against older bodybuilders is that they are lean but they don't have any muscle - they don't have a butt," he said. "Believe me, I got a butt! I don't think that I am losing anything. I think that my butt is bigger than it was before."

For Bass, the hip replacement has become, in a sense, a badge of honor: The photo he used for his latest book is a softly lit nude that accentuated his signature abs and the surgical scar on the right hip.

Terry Todd has said that Bass understands that his physique is more than a finely sculpted collection of muscle and bone. He and his photographs are playing a historic role, he said, in the fields of aging and popular culture. "I think that he has understood his role more clearly as the years have gone by," Todd said.

Bass's approach to aging underscores a trait I've seen in older superfit persons:

They use knowledge, experience, and sometimes a healthy dose of independence to find a way to

ADAPT.

He placed a huge bowl of food in front of me that looked absolutely awful. I love vegetables, but not in my cereal, and I am not sure I had ever tasted soy milk. On the table in front of me was a teaspoon. I was to eat this prodigious concoction not with a tablespoon but with a teaspoon. The idea was to slow down my consumption so I didn't eat past the point of feeling full. There was, however, an implicit understanding that I should finish the whole bowl. The breakfast turned out to be surprisingly good - nutty, sweet, and almost buttery. The grains gave it some heft and the fruit and vegetables went well together.

Later in the morning he offered me an apple. Bass often has an apple and a quarter-cup of salmon as a mid-morning snack to keep his blood sugar at a high level.

Before lunch we walked on a patchwork of trails on the eastern edge of Albuquerque that threaded through public land a few blocks from his home. Sometimes he and Carol will walk farther into the Sandia Mountains. Bass has timed himself getting to the top. He told me that he knocked 10 minutes off the climb when he began taking the supplement creatine, which supplies energy to muscles. He also takes a multivitamin and vitamins C and E. But this was a recovery day and we walked leisurely through a moonscape flecked with withering grasses and cacti. On our return, the trail provided a sweeping vista of the city and the Rio Grande Valley.

"Most people think that aerobic exercise is boring," he said. "Well, the way most people do it, it is boring - going to gyms and reading newspapers. If you do it right, if you have a nice place to walk, you get revitalized."

When we came back, Bass served lunch: special peanut butter formulated with eggs and flax-seed oil on toasted whole grain break, a handful of carrots, and a large mug with equal portions of plain low-fat yogurt and plain soy milk. I was again handed a teaspoon. Bass quartered the sandwich for the same reason. "These are kind of mechanical ways to slow you down," he said.

By mid-afternoon, we were driving to his office in his Mercedes E55, and as I was eating a Tiger's Milk nutrition bar he had handed me, he gently admonished, "Eat slow."

Clarence and Carol often eat large salads, bread, and fish, chicken or eggs for dinner. But that night we went to a restaurant that served traditional New Mexican cuisine. Carol, who is as lean as Clarence, ordered a large burrito, without cheese, and ate it all. Bass slowly polished off a plate of huevos rancheros, sunny side up, and he shared a plate of Navajo fry bread with us. The two of them shared a Mexican flan (custard that is drizzled with caramel sauce). Bass did not have any alcohol, although he occasionally will have a glass of wine. He is abstemious because "alcohol weakens the control I usually have over my appetite," he wrote in one of his books, The Lean Advantage. "It seems to anesthetize my stomach and encourage me to go on eating beyond the point where I would normally be full and satisfied."

The Lean Advantage, Volumes 1, 2 and 3:

http://www.cbass.com/PROD02.HTM

For a snack at night, Bass has a slice of toast with almond butter, honey, and Benecol, a product intended to lower dietary cholesterol. He quarters the toast and eats a section every 15 minutes.

Bass felt he needed to drop 4 or 5 pounds and knock down his body fat by a few percentage points before he posed for his photos at 70. Six months before the shoot, he had preliminary photos taken. "I didn't like them," he said. "I had some extra weight around my love handles and lower back - pretty much everybody has it." He cut down by backing off slightly at every meal: a little less cooked grain and flax seed at breakfast, smaller amounts of peanut butter, and one fewer slice of bread at dinner.

Ripped Enterprises is located in a one-story office building that housed his legal practice before Bass went into the health business full tie. Two of the rooms are jammed with an array of weight machines, free weights, and other equipment positioned atop aging gold carpeting. The walls are covered with mirrors and pictures of bodybuilders. One room is devoted to lower-body exercises; the other, is for the upper body. There are plates, benches, cables, dumbbells, barbells, and a pair of weightlifting shoes. Each room contains impeccably maintained metallic blue Nautilus equipment from the 1970s that Bass bought from Arthur Jones, the founder of the company. Bass was so jazzed by the technology of pulleys and cams when it first came out that he and Carol flew to Florida to meet Jones.

He keeps additional equipment at home: In a room next to the garage, he has a Concept 2 rowing machine, a stair stepper, a Schwinn Airdyne, and a Lifecycle. In his garage an entire bay is outfitted with a squat rack, old-fashioned kettlebells [yes, it wasn't that long ago they were referred to as old fashioned!], weight-resistance machines powered by an air compressor, and a contraption called a glute-ham developer [again, 'contraption - not that long ago].

Bass had a heavy weight-training session the day before, his biggest of the week, so I didn't expect a big demonstration when we arrived at his office. But when I asked about his favorite lifts to keep his abs so buff, he knelt down in front of a machine with a cable and pulley. He pulled down on the weight and let his oblique muscles do the work. At the bottom of the pull, he slowly raised the weight - again relying on his abdominal muscles. The exercise is often practiced with the subtlety of a pile driver. With Bass, it was almost sensual - an embrace between man and machine.

"Clarence can't wait for the next workout," said Carl Miller, who owns a gym in Santa Fe. The key to lifting weights over many years "is that it has to capture your imagination so that you keep looking for ways to get better," Miller said. "You are always looking for a new training technique."

Bass has picked up and discarded an array of exercises and lifts over the years. At 60, for example, after more than a 30-year absence, he began incorporating technically more difficult lifts such as the power clean, power snatch, and squat snatch, which require quickness, strength, and good balance.

Bass exercises six or seven days a week, but he lifts weight only two of those days. He sits down with his workout diary before each session and plans what he will do. His diaries are 500 pages apiece and he's accumulated dozens of them over the years. Over time he has added more aerobic training for his cardio-respiratory system as well. On periodic visits to the Cooper Aerobics Center in Dallas, his fitness was judged by tests on a treadmill or stationary bicycle consistently put him in the top category for his age.

Bass is a disciple of the HIT (high-intensity training) school of weight training. Early proponents included Arthur Jones (the Nautilus founder) and former world-champion bodybuilder Mike Mentzer. Advocates of HIT believe the best way to build muscle mass is with short, infrequent, but very hard workout sessions rather than hours of exercise almost every day.

Typically on Sundays, he will work his entire body with weights, making more than a dozen lifts that push him to the upper end of his capabilities. After warming up, he will do only one heavy set or each lift - 8 to 15 repetitions. "The key point is that I do not wear myself out before I get to the set that really counts," he told me.

Three days later, he lifts weights with his upper body and then climbs on a Lifecycle, a computerized stationary bike for 20 minutes and pedals hard at various resistance levels. By constantly changing the intervals and intensity, he is mimicking what he believes is humans' ancient need to exert short bursts of energy.

Three days later he does crunches and works sundry core muscles. He also does about 20 minutes of hard pedaling on his Aerodyne, which requires pedaling and back-and-forth arm action. On other days he goes on walks for 30 or 40 minutes.

Bass has pushed back the hands of the aging clock because of his triad of diet, aerobic exercise, and weightlifting. His metabolism burns calories as if he were a youngster because he continues to stay almost as active as one. Strong, exercised muscles, even when they are resting, burn more calories than less-trained muscles. "Anyone wanting to lose or control weight should, in addition to eating less and exercising more, try to increase lean muscle mass," writes physician Andrew Weil in his book, Healthy Aging: A Lifelong Guide to Your Well-Being. Weight training, he said, will "keep the metabolic furnace burning bright."

I asked Bass about whether he ever thought of cutting back. What is the difference, I asked, between him and a 70-year old man in excellent health who walks a little and putters in the yard?

"One thing he isn't trying to do is challenge or improve himself," Bass said. "It sounds like he's an old man, and that doesn't excite me. I think you have to find something that excites you, that motivates you, so you want to get out of the bed and get down to the gym."

Aging is Inevitable

But Bass isn't bulletproof. There is the osteoarthritis in his lower back that has forced him to give up the use of his Concept2 rowing machine and traditional squats. He also has a weakness in his left shoulder and mild atrophy in his left triceps. On a visit to the Cooper Clinic, doctors discovered a buildup of calcium in his left anterior descending artery that requires the use of a statin drug to reduce cholesterol.

At 67, Bass also found that he was retaining excessive amounts of urine in his bladder. After several tests, he had surgery to remove abnormal lobes where urine drains from the bladder through the prostate.

"The whole situation went against my experience so far and my optimistic view of the future," he wrote in Great Expectations. "I expected a few problems to come with aging, but frankly I didn't expect this so soon. I went to the doctor with what I considered a minor problem - and I ended up in surgery."

When he first met his urologist, the doctor had concluded that Bass would have to insert a device into his penis three or four times a day to keep the urinary pathway open. It seemed barbaric. Bass responded with understandable reluctance; later, after it was clear he would have to do something, Bass countered with using the device less. He has been able to pare down the number of sessions to once a week, with his doctor's blessing.

Then, at 68, Bass had his right hip replaced. Neither Bass nor his doctors know why he needed the surgery, although hip replacements are the second-most common orthopedic surgery after knee replacements for people 65 to 84, according to a 2007 study by the federal Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Fifty years of weight training might have been the cause. Bass knows his share of old weightlifters who have had a hip replacement and who usually trace it back to an injury. "But I don't think that I would have gotten this far had I not been exercising," he said.

Rather than undergo a traditional hip replacement, he learned about an alternative procedure that causes less tissue damage because the hip is replaced through natural breaks in the muscle. His recovery was faster, although it left him with weakness in his hip flexor and numbness in his upper thigh. I noticed when we went for a walk, he moved stiffly at the beginning.

Bass talked to me matter-of-factly about his ritual of keeping his urinary pathway open. The practice changed from dread to just another regimen in his life. He checked with knowledgeable friends and did his own research to find a better procedure for his hip replacement that was more fitting for his active lifestyle - even though it meant a trip to Houston for surgery. He has dropped some exercises that cause problems for his body and added new ones. To get around weaknesses such as his osteoarthritis, he showed me how he clasped a belt around his waist that was attached to a biceps curl bar with weights (hip belt squat). This way he could still do a squat and work his leg muscles while keeping pressure off his spine.

"One of the raps against older bodybuilders is that they are lean but they don't have any muscle - they don't have a butt," he said. "Believe me, I got a butt! I don't think that I am losing anything. I think that my butt is bigger than it was before."

For Bass, the hip replacement has become, in a sense, a badge of honor: The photo he used for his latest book is a softly lit nude that accentuated his signature abs and the surgical scar on the right hip.

Terry Todd has said that Bass understands that his physique is more than a finely sculpted collection of muscle and bone. He and his photographs are playing a historic role, he said, in the fields of aging and popular culture. "I think that he has understood his role more clearly as the years have gone by," Todd said.

Bass's approach to aging underscores a trait I've seen in older superfit persons:

They use knowledge, experience, and sometimes a healthy dose of independence to find a way to

ADAPT.

No comments:

Post a Comment