Man, it's almost more work finding articles Dale hasn't got on the site than it is to type them up.

Strength & Health April 1972

The athletic career of George Michael Frenn began at North

Hollywood High School, in the San Fernando Valley, in February, 1957. He

started out in track and field as a runner just to be with his then close

friend Brad Bechtol. Brad’s father, Beck, was a crack 440 yard dash man of the

early 1920’s at Sain John’s University. Beck had encouraged his son to go out

for track with the idea of trying to match Beck’s early high school and college

performances. This Brad did, going on to receive a college scholarship for his

running ability. In the meantime, athletics was just the thing that George

needed to start out his life because he had lost his own father when he was 4

years old and being the youngest boy of seven with one older sister and one

younger sister, he did not get the attention and guidance in the developmental

years of high school. So, in a sense, athletics gave him a direction and a set

of goals worth shooting for.

The now strong man spent his 6th, 7th,

8th and 9th years at Sain John’s Military Academy in Los

Angeles where he learned a disciplined life of regimentation. While at that

institution, he tried out for every team sport and could only make 2nd

and 3rd string at the standard sports that young boys play. So

George gave up all hope of playing athletically until he discovered track and

field in high school. He really dug the sport because the athlete could

progress at his own rate and there was never a team cut because you could only

be given a competition suit when you were good enough to perform with the other

athletes on the field. So the harder he trained the better he got and finally

in his senior year, Johnny Sanders, now the director of player personnel for

the Los Angeles Rams, who was track and field coach, gave George a suit for the

one and only track meet that he took part in high school. George did very

poorly in the 220 yard dash and the 880 yard run but he still loved the

competition and he still wanted to participate. So, at the end of the year he

asked his coach about the possibility of getting a scholarship to Abilene

Christian College because that’s where Bobby Morrow went to school and he was

George’s idol. Coach Sanders told him to forget about getting a scholarship to

A.C.C. but he suggested that he enroll at a local junior college and start his

college career there. It should be noted that George tried out for the high

school football team but again failed to make the team for several reasons. He

was in good shape for that period of his life, but the 1959 team at North

Hollywood High School had one All-America and 2 All-American honorable mentions

plus 5 All-L.A. City linemen. In short, the competition was very tough and he

had to settle for 2nd string junior varsity. Also, weight training

had just been introduced to the high school program and no one knew very much

about this method of training other than to say “don’t life too much because it

will make you muscle bound.”

After graduation in June, 1959, George was at a major

crossroad of his life; should he go to college or join the army. Truthfully,

his high school counselor told him that he could never do college work and

consequently had always put him in a shop program for the duration of his high

school days.

It proved to be an easy decision to make in that George

continued to run during the summer of 1959. In July of that year, he went to an

all-comers track and field meet to run the 100 and 220 yard dashes. He came in

last in both races. After the competitions, Gary Comer, a star 440 yard dash

runner made a wise crack to the developing Frenn. He said, “Why don’t you get

into the field events where you belong and stop running?” George was insulted

and got up and walked down the field. It should be pointed out here that George

was no lightweight by sprinter standards. He was 5 feet 11 inches tall and

weighed 185 pounds and truly not very strong. But he had one thing going for

him that few ever really achieve: that is the genuine desire to take part – to

participate for the sheer pleasure of doing something really well. A few

moments after drying his eyes from the Comer insult, it was announced that 2

Olympic champions would compete that evening. They were Harold Connolly, his

now close partner in international hammer throwing and the incomparable Parry

O’Brien, the shot-put and discus king.

Well, the evening was just right; warm, balmy, and quiet.

Harold stepped into the throwing ring and let loose with a great effort. The

silver ball whizzed through the air and George immediately tripped out to the

event. He went around asking who that man was an what is it that he was doing.

He was told that was the hammer throw and that there were very few throwers in

the United States. Well, George went home and he began to think about what he

saw. In October of that year, he finally got up enough courage to call Harold

and introduce himself and ask for some information about the hammer throw.

Harold gave him a book which he had written about the hammer and George began

to study the event. George made his first hammer at Cannon Engineering Company

out of a block of steel and Ted Cannon made the handle for him and attached it

to the block by means of a cable. After 2 months of training with this

contraption, he finally bought himself an official hammer for $26.00 from a

sporting goods store. George entered his first meet with the hammer and got

second with a throw of 90 feet 1 inch. Not bad, except that there were only two

people in the contest. The winner, Tom Pagani, threw 180 feet and after the

competition gave George his first real lesson in hammer throwing. Well, in the

meantime George knew that strength was important because all the throwers were

very large and seemed quite strong. So again George asked Harold for help and

again Harold responded positively. He took George down to the old alley gym at

Muscle Beach where all of the West Coast strong men trained and he took George

through a complete workout once. He instructed George in all of the proper

exercises for throwing the hammer and then he said, “George, you are on your

own. Train hard and you might make it.” This was about the only encouragement

that George got except from the Bechtols. George continued to train at the

alley gym and then at the old Vic Tanny gym at 4th and Broadway in

Santa Monica until he met his coach and close friend, Bill West. This chance

meeting of George and Bill proved to be the greatest thing that ever happened

to George because Bill was able to get the very best out of his young pupil.

George had a strong frame and excellent constitution and he could take the work

that Bill dished out. This meeting took place in February, 1965. Bill and

George started training together on March 6, 1965 at the now famous Westside

Barbell Club. While all of this weight training and running was going on, George

finished a semester at Pierce Junior College, a semester at Abilene Christian

College where he just could not hack the strict religion that was placed on the

students, and 6 semester at Valley Junior College. While at Valley, he earned

his college letter in track and field as a discus thrower under the coaching of

George Ker. Coach Ker also gave George

his first lesson in throwing the 35 pound weight. This event is similar

to the hammer throw but the implement is shorter and it is heavier. After

receiving the Associate in Arts degree from that institution our man about town was supposed to enroll at

the University of Southern California but that scholarship was cancelled

because of a dispute with the narrow minded athletic director, who just could

not see giving a scholarship to a hammer thrower. At this point, we are up to

February, 1964. Athletically, George had placed second in the National

A.A.U. Track and Field Championships in

the hammer throw – yes – believe it or not. In just three years of throwing,

young Frenn, at 21 years of age was the second best thrower in the country and

qualified to make a tour to the Soviet Union. Unfortunately, Harold bumped

George off of the team and he did not get to throw against the Russians, but he

did stay on tour and threw in Poland, England, Romania, Germany and since that

year of 1964, he has competed in just about every major country on the face of

the earth. He has made three trips to the U.S.S.R. with the U.S.A. National

Track and Field Team and 2 trips to the Pan-American Games: Winnipeg, Canada

and Cali, Columbia placing third and second, respectively.

Within the 10 years of Frenn’s athletic career, he has

suffered three major physical injuries. The first took place in high school

while practicing hurdling. Many coaches have their men run the hurdles with a

removable crossbar. This is done in the event the athlete kicks the bar with

his training leg, he won’t kick over the entire hurdle, only the cross bar. In

this particular instance, the bar that George used was too long, so that it

happened that he did knock it off with his trail leg. As he landed back on the

ground from jumping the hurdle the crossbar propped itself up, one end on the

ground, the other pierced George’s lower abdomen and came out his stomach. This

freak accident required 50 stitches to close and he lost one month of training

time.

The second serious injury was a back injury. While squatting

in the old Vic Tanny Gym in Santa Monica, George was trying heavy poundages two

days in a row. Apparently, he was more fatigued than he realized as his back

went out and he lost muscular control of his right leg instantly. This back

injury plagued him all through the track season and this was the probably

reason that he did not make the 1964 Olympic Team. The injury eventually healed

after a great deal of stretching and deadlifting. Doctors wanted to operate and

remove a disc but he would not let them do it. This injury took place in April,

1964.

The third major injury George went through was the weirdest

of them all (not sure how it could be weirder than being impaled on a hurdle

crossbar.) It happened in February, 1966 just 3 days prior to the indoor

nationals in track and field. George was throwing the 35 pound weight at

Cal-State Long Beach and listening to his favorite music at the same time –

that of the great jazz pianist, Erroll Garner. This music psyches him up

because of the great rhythm that Garner creates. Incidentally, George plays the

piano for his own enjoyment and if he really gets bugged he might pick it up

and throw it. This particular throwing session was the final workout before

going to New Mexico to do battle with Harold and Ed Burke for the national

title. George had been over the then world record in that session on at least 8

throws. In fact, a small crowd had gathered and they were awed by this terrific

display of throwing power. George looked at Gary Ordway the discus thrower and

said, “this will be my last throw.” Well, the weight was picked up and spun and

he was about to release it when it got caught on his glove. The force whipped

George around and his right leg got caught against his left leg an instantly he

suffered a spiral fracture of the right fibula. Talk about depression, well

after the cast was applied, George went right over to Bill West’s house and

told him. They then both agreed that George could bench press for the next 13

weeks and this he did. While in that cast, George did some other remarkable

things also. For instance, he began to do quarter squts after a 4 week period

of recovery while still in the cast. You may remember the great contest that

was held in San Diego between Pat Casey and Terry Todd. Well, George was in

that one also. Only he lifted in a cast.

He bench pressed 420 pounds and just missed 440 pounds. He

then squatted 600 pounds believe it or not, he has the pictures to prove it, and

then he deadlifted 585 pounds while in the cast. One week later, he entered the

Coliseum Relays and took the cast off and threw the hammer 191 feet for third

place. He also has thrown the hammer with the cast on 151 feet 7 inches.

In 1964 George enrolled at California State College Long

Beach and earned his letter as a hammer thrower and discus thrower as he did at

Abilene Christian College thus becoming a three year letter man at three

different institutions. While at Cal State, George took a bachelors degree in

Physical Education and one in Psychology. He also earned a Masters Degree in

Physical Education and three California State Teaching Credentials.

During the time of this education, George worked hard with

Bill west and together they won every major contest on the West Coast in

powerlifting and George even won the California State Heavyweight Olympic

lifting title in 1967. In 1971, he was second in this competition. The true

story of Frenn on Olympic lifting is the fact that it is not applicable to

hammer throwing and so he has never put any real time into these lifts, but he

has spent most of his time powerlifting because it applies to hammer throwing

and because Bill West is his close friend and Bill does not Olympic lift.

To list the athletic accomplishments of George Frenn would

take too much space so here are the major awards he has won. He was selected

for the cover of Sports Illustrated magazine July 6, 1970. In 1970 he won the

U.S.A. championships for throwing the 16 pound hammer, the 35 pound weight

indoors, and the 56 pound weight outdoors. He repeated this same trio in 1971

and he is the only man in U.S.A. track and field history to ever do this. In

track and field he holds the following records: American and World Records for the 35 pound weight

indoors, 74 feet 3 ½ inches; 35 pound weight outdoors 68 feet 7 ½ inches; 56

pound weight for height, 17 feet 2 ½ inches (George was the first man to go

over seventeen feet) and he has officially thrown the hammer 232 feet 7 inches.

In powerlifting, he was the fist man to get through the 800 pound squat barrier

and the first man ever to total 2100 pounds. He holds the following records:

American 242 ½ pound class full squat at 853 pounds. He has held the 242 total

record at 2100 pounds and the superheavyweight squat record at 815 pounds and

the deadlift record at 812 ½ pounds. His best official bench press is 520

pounds. Again, here is an exercise that he can not practice very much because

it hinders his hammer throwing but most people don’t realize this.

There is an interesting story about George and the 56 pound

weight. Andy Magna, a New York stock broker sent a 56 pound weight out to

George as a gag. The freight alone was $14.00. The strong man decided to try to

throw it in a competition. He did – and broke the existing World Record by 3 ½

inches. However, when the weight was weighted, it was found to be 5 grams too

light and George did not even get credit for the record. But he was given

another opportunity to throw it at the Rose Bowl and this he did, setting a new

World Record of 48 feet ¾ inch. Immediately after that throw, Harold Connolly

came running up and gave him a great hug and said, “George, you have just

immortalized yourself. No one will ever break that record.” Bob Backus had held

the previous record at 45 feet 7 inches and this record has stood for 14 years.

In 1969 George upped the record again to 49 feet 7 ½ inches and again in 1971

to 49 feet 8 ½ inches. He has a standing offer of $100.00 to anyone who can

break the 56 pound weight throw record if he fails to set a new record in a

follow up competition. Any takers?

The Frito Bandito, as he is sometimes called, has won 10

National Championships: 1 in powerlifting, 2 in hammer throwing, 2 for the 35

pound weight throw, and 5 for the 56 pound weight throw. After all has been

said and done it is of interest that Bob Backus, the former great track and

field man is probably Goerge’s greatest idol along with Harold and Parry. Bob

took notice of the developing youngster and always provided encouragement and

coaching for George whenever he visited Bakus’ Boston Gym. Bob has even paid

expenses for the champion weight thrower to the National Championships just so

he could see George throw.

Probably George’s best and closest friend is Curt Stevens, a

psychological social worker. They met for the first time in May of 1960. Frenn

was having trouble staying in the circle and he would foul out in almost every

competition. He was under a great mental strain so he decided to get some help

through the school counseling service at Valley College. They have been working

together ever since in in-depth psyco-therapy. “This was the smartest thing

that I have ever done. Everyone needs someone that he can discuss anything with

and I have been able to discuss my athletic hang-ups with Curt and he has

helped me straighten them out. This has helped my track and field and

powerlifting competitions greatly” says George. George feels that between Curt

Stevens, Bill West, Harold Connolly, and Bob Backus he received the guidance

and encouragement that got him to where he is today.

What lies ahead for the 30 year old National Champion? Well,

in track and field he wants to make the 1972 Olympic Team and throw the hammer

over 240 feet this year. In powerlifting, he wants to squat 900 pounds possibly

in 1972. Now, the question comes up, “How about a contest between Jon Cole and

George Frenn?” Well, you probably will never see such a contest until after the

1972 Olympic Games because George cannot practice the bench press. However, if

the bench press were eliminated for a contest and the squat and deadlift were

just used, well, that’s another question. Frenn has never been beaten in the

full squat by anyone. And few have ever beaten him in the deadlift and now that

he has learned the secret of the heavy deadlift it is doubtful that he would

lose such a contest to any one. “I know I’m not the world’s strongest man but I

know that Jon Cole is not either.”

Frenn feels that this is an impossible concept to achieve

because nobody is up everyday. You get suck, lose weight and the like. The

world’s strongest man should be strong every day. Suppose you have a bad day

like Cole had at the 1971 Powerlifting Nationals? Are you still the world’s

strongest man even if you set records in competition after the Nationals? Frenn

says no. The champion or the world’s strongest man should always win and always

be up. Since this is impossible to attain, the phoney title should be dropped.

He would be in favor of a title like world’s best Olympic lifter or world’s

best powerlifter but that would be it. Anyone foolish enough to think that he

is the strongest man in the world is on an ego trip. Even Paul Anderson, who

has moved the greatest amount of weight in one lift refuses to call himself the

world’s strongest man. “Believe me,” says Frenn, “the world’s strongest man has

not ever been found. There is always someone to take his place or he simply has

not been found yet.”

George likes to keep himself in shape all year round and

seldom lets his squat go below 700 pounds. He has squatted 700 pounds twice a

week for the last 3 years.

George has taught school for three years but in order to

make the Olympic Team, he resigned to devote full time to training and to a new

career that he has dabbled in off and on, that of picture making. In August of

1971 the North Hollywood strong man met David C. Detert of San Francisco, an

enterprising young man who does entertainment production while managing the

Detert Chemical Company of San Francisco for his father Earl. David was

interested in making a film and had many ideas similar to George’s so the two

formed a production company known as Cinema Associates Ltd. They are currently

working on a film about the 1972 United States Olympic Team which will be

televised nationally prior to the Summer Games. The film uncovers many of the

sacrifices that international and Olympic caliber athletes must make in order

to represent their country in the Games. The film is a news documentary type

which has much sports action and commentary from many of the nation’s leading

amateur athletes and promises to be one of the finest works of its kind ever

presented for viewing. Because of his commitment in the film industry, George

has not had the time to answer the many fan letters that he has received but

hoped that everyone will excuse this.

In closing, Frenn doubts seriously that we will ever see

powerlifting in the Olympic Games. For one thing the Olympic Games have too

many sports now, the Games are too big. For another thing, the rules are too

strict and they are not uniform around the world. Finally the present concept

of bodyweight classes is old and out0moded and this seriously hurts

powerlifting at the international level. If powerlifting maintains the same

bodyweight standards as Olympic lifting then the power men are going to be held

back as well as the sport. Most foreign countries have little men in the Games

as lifters and a change of the bodyweight classification would eliminate these

countries from competition.

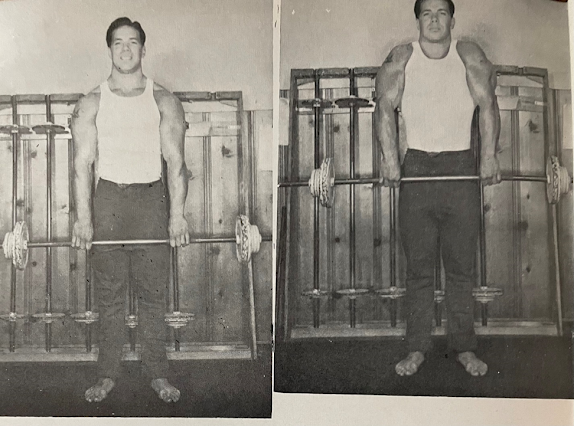

The complete training routine that George is on is here and

as you can see he really gets it on. Thoe that train with him can tell you that

he actually handles that much weight in his regular training sessions without

really getting psyched up. If you intend to follow it, great, but get about 6

years of experience behind you first. George has done it. Maybe you will also.

George Frenn’s Powerlifting Training Schedule as of

January, 1969

He is the 1970 National A.A.U. Hammer Throw, 35 Pound, and

56 Pound Weight Throwing Champion. In 1967, he won the National A.A.U.

Powerlifting Championship. He is the American Record Holder for the 2 weight

throws and the 242 ½ pound class full squat with a lift of 819 pounds (now 853

lbs.)

“I train only on Tuesdays and Saturday with the weights and

I throw the hammer and run on Mondays, Wednesdays, Thursdays and Saturdays.

When I train for the Powerlifts I do bench press; otherwise, I never do any

pressing movements as it hurts the hammer throw.”

TUESDAY

Bench Press

Bench Squats (20 inch bench)

Low Box Squats (14 inch box) 4 sets x 1 rep

Lat Pull Downs: 3 sets x 10 reps heavy as you can go

Good Mornings: 3 sets x 5 reps 135, 225, 315, sometimes 425

Power Cleans: 5 sets x 5, 4, 3, 2, 1

Triceps Extensions: 3 sets x 10 reps heavy as you can go

For the bench press and the bench squat, do 12 sets. Low Box

follows bench squats

“As for Saturday’s training, I do only the bench

press, full squat, and deadlift. For the bench press schedule, follow the one I

use on Tuesdays. Use the bench squat schedule for your full squats. The sets

are the same but the poundages are not quite that heavy. During the hammer

throwing season, I do not bench press, so I substitute the power clean and

snatch for the bench press. Follow the power clean schedule for these two

exercises.”