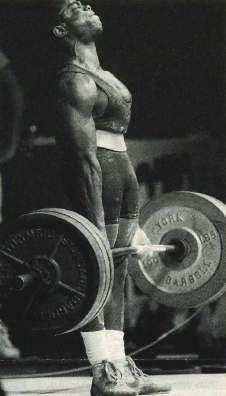

Lamar Gant, side view.

I have no doubt that the primary cause of overtraining is the psychological fulfillment that most lifters get from being in the gym often and doing "a lot" of exercises. As a competitive lifter, a greater degree of satisfaction would come from increasing one's official total and of course, each lift.

But the majority of lifters prevent their own gains by doing a great deal of unnecessary work. For example, the bench press is typically over-trained by many athletes and lifters because the lift and its associated assistance work develops the very "showy" muscles of the upper body. That increase in certain upper body measurements may enhance one's ego, but it doesn't necessarily equate to heavier totals.

Some would not even see this as a deterrent to the performance of adjunctive movements, rationalizing their lack of bench press progress with the self-satisfaction that comes from an actual or perceived increase in upper body size and muscularity.

Very few lifters look forward to the deadlift or any of its assistance exercises. However, they still train the deadlift for too many sets or too often to allow for full recovery between sessions because of the same compulsion which drives them to perform a multitude of bench press and arm-related exercises.

The deadlift, if done correctly and at the proper level of intensity, is brutal. There is no other way to accurately describe it. Wilbur Streeter, an excellent masters level lifter who corresponds with me often, is a superb deadlifter and coach and has often remarked that men and women will not do this one lift "hard and heavy enough to really approach their true limits."

While refusing to train the lift hard enough and to make the commitment to suffer the inevitable physical discomfort that comes with that commitment, lifters will to too many "top" sets. They do little for actual strength stimulation and end up eroding their ability to recuperate for future workouts. When told it would be best to deadlift once every ten days, two weeks, or even once in every three weeks, they ignore the advice and continue to train the lift once or twice per week.

They are, in most cases, afraid not to train the deadlift. They have the delusion that "more work" will take the place of productive, intense work, ignoring the increasing pain and tightness in the low back, fatigue in the thighs and hips, occasional "stiff necks" and trapezius spasms - all signs of overtraining and a lack of rest.

The lifter's need to be in the gym, training a lift lest they fall behind the competition makes little sense when they could be training productively in each and every deadlift workout. To compound the problem, it is assumed that assistance exercises re necessary for every phase of this lift.

I always enjoyed power rack work. Bill March was an early lifting influence on my and was one of the first advocates of power rack training. We had great sessions at the York Gym and I found that I was able to lift extremely heavy weight in a number of partial-range movements. The deadlift from a point just above or in the middle of the patella was a favorite. At a bodyweight of approximately 160 pounds, I was able to complete 5 or 6 reps with 730. This was a great "feat of strength" and never failed to get rave reviews in the gym. Larger lifters would shake their heads and note how impressed they were with my ability to lock out these very heave weights. (Unfortunately, on the day of any meet, my competitors were not so impressed!)

This short-range strength was never transferred to my competitive deadlift. Alterations in style and stance helped little. It seemed that no matter how strong I became from the rack, I could never apply it in a competitive situation. Yet, Jay Rosciglione, one of the best lifters in the United States for many years, often used the partial deadlift from knee height and has had great success with it.

Power rack work is very strenuous, perhaps more strenuous than it appears. It is important that two precautions be taken if one chooses to include any partial deadlifting movements in the workout.

First, do not use the rack too often. Once every two to four weeks will be enough for most lifters. The inroads made into one's ability to recover are quite great.

Secondly, use moderately high repetitions. One can use enormous weights in the partial deadlift. This exposes the connective tissue in the lumbar spine area to tremendous force, increasing the possibility of injury. Use perfect form, taking a second or two to "set" before each rep, and do 1 or 2 tops sets in the 10-15 range. These higher reps will allow one to build a great deal of emotional resiliency while building strength.

We always stand on an elevated block when doing stiff-legged deadlifts. This allows for a complete range of motion throughout the lumbar spine region and assures that the hamstrings and hips are receiving their share of the load.

Doing "regular" deadlifts while elevated also allows for a greater range of bar movement. But it must be emphasized that one should not elevate excessively because the deadlift motion is then significantly altered and could lead to injury or a subsequent breakdown in form once you're lifting the bar on the competitive platform.

Many lifters with preexisting lumbar injury have been reinjured because they chose to reach "too low" when doing their "deep starts." An inch or two of elevation might help one's ability to start the weight from the floor in a competitive situation, but I see little advantage in standing on a four- or six-inch block while doing this movement. Again, it may endanger the back and lead to subsequent form problems.

One of the problems lifters have is an inability to choose what is best at a particular time. I've seen programs that required the athlete to do regular deadlifts and included power rack work for short range movements, plus deep starts to help their ability to break the weight off the floor. All of these movements are strenuous and if the compulsion to do "something" for each phase of the lift forces one to do a number of heavy movements, the lifter is left in an injured and/or over-trained state.

The deadlift itself will take a great deal of effort and to compound this with another heavy assistance movement is foolish and counterproductive. If the lifter insists on including two or three movements so the traps and scapulae retractors receive their fair share of work, over-training is almost guaranteed.

It's important to first learn how to deadlift properly with heavy weights. Once this is achieved, there is little need for any assistance work if one is demonstrating constant and consistent progress in the primary lift.

If progress stalls, or if the athlete becomes the victim of burnout, a switch to stiff-legged deadlifts or some other deadlift variation might bring them back into the fold of progress. Alternating stiff-legged deadlifts in one week with regular or deep-start (deficit) deadlifts in the next week, for two months or so has also proven effective.

Most well balanced programs will include some form of exercise for the upper back musculature, so the deadlift, in conjunction with this work, should provide the back with plenty of work. I know that my upper back and lats are more sore - not from those exercises that give them "direct" work - but after performing stiff-legged deadlifts with very heavy weights and high repetitions. Controlling the bar and maintaining proper position makes this area sore beyond description.

Squatting or other hip/thigh exercises will bring strength stimulation to this area, which of course translates to a better deadlift.

Many lifters include the leg press as a deadlift, not a squat, assistance exercise. If you feel it is needed, do it; and don't worry what it is specifically helping as long as it doesn't detract from your lifts due to overtraining.

Judicious choices and common sense are the keys to successful deadlifting. If you need two weeks between sessions, take it and ignore the compulsive calling to deadlift more often. Often one or two top sets are all most men or women need if those sets are truly taxing.

Pay little attention to those who suggest more, if more leaves you drained and/or injured.

Choose wisely, rest well, and recover, then deadlift the house!

No comments:

Post a Comment