To facilitate ease in loading, Sam Sulek Sr. deadlifts

from inside the rack. Here he struggles

to double at 674. Note how

the knees are forced out.

More from Doug Nassif here:

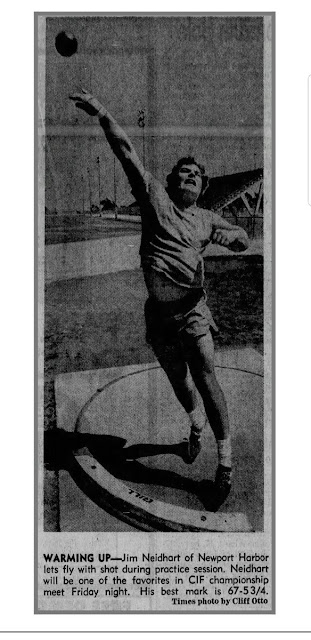

". . . And in this corner -- from the Oakland Raiders . . . Big Jim Neidhart!" screamed the wrestling announcer as this extremely large athlete lumbered slowly into the ring. But Neidhart is massive, and it seemed as though he made his entrance in sections.

"Ahhh," gasped an obviously captivated pro-wrestling fan. "It looks like he's half the team!"

It was just another night for this very special weight trained individual. Recently placed on waivers by the NFL Oakland club, Neidhart, all 285 pounds, was not so quietly making his living tonight at the Olympic Auditorium in Los Angeles as a professional wrestler. Pay for what turns out to be a 25 minute bout? $135.

His 195 pound opponent, a Texas lad with blonde locks and innocence oozing from a cherubic face, took one quick, nervous glance at Neidhart's twitching, menacing traps and must have prayed that there had been some kind of mistake. More than 8,000 bloodthirsty fans were staring openmouthed as this sweating, grunting human mountain stretched and flexed through his warmup.

Just before the opening bell rang, the Texan's knees were (I swear) slightly quivering. Promoters throughout the country understand that Neidhart the wrestler commonly evokes this kind of reaction.

In Canada, they call him simply "The Wall."

For the 25-year old Neidhart, lifting in all its various forms has been a constant driving force since he took his first turn at the bench press in seventh grade.

After winning the 1975 national high school shot put championship (69'3") and representing the United States on an AAU tour through Russia, East Germany and Polandm, Neidhart, despite recruitment pitches from over 200 college football coaches, chose to put the shot, accepting a track scholarship from Perennial West Coast powerhouse UCLA.

But after two years there, one at the University of Hawaii and a disastrous season of red-shirting at Long Beach State, Neidhart says he "got tired of living hand to mouth and decided to use his muscle and shot-putter's explosive speed to land a professional football contract.

His strength totals were impressive: at a track clinic his junior year, Neidhart recorded a legal 570 bench, 689 squat and 410 power clean in the course of one afternoon! He deadlifted 720 in high school and inclined (45 degrees) 485 in the UCLA weight room.

Locking horns with a 674 squat double.

"I've never lifted to impress anyone or to set any kind of record," Neidhart explains. "I've never entered any kind of powerlifting or weightlifting meet. I lift to make myself stronger for whatever sport I'm training for at the time."

One look at Neidhart's lifts were enough for the Dallas Cowboys and in May, 1979, the signed the track man with intentions of playing him at defensive tackle. Then, during the fifth week of double sessions an intricate court proceeding called Jim away from the Dallas camp, prompting Cowboy brass to place him on wavers.

Discouraged but not ready to hit the skids, Neidhart was summoned that Autumn to Calgary, Alberta, by Canadian professional wrestling kingpin Stu Hart. With less than $100 in his pocket, Neidhart packed his lifting boots and sweats and headed north, determined to make a name for himself in a business where superstars can gross $500,000 a year. The big American became an instant sensation in Western Canada.

"In my many years in this sport I have never seen a young man with the combination of strength, speed and magnetic appeal that Jimmy has," exclaims Hart, a wrestling legend himself. "Neidhart's potential is virtually unlimited."

So the Southern Californian spent a freezing, lonely winter in the Canadian hinterlands, wrestling in dreary, faraway sounding locales like Red Deer, Edmonton, and Regina, slowly breaking into the tumultuous pro grappling world, taking the bumps and bruises as they came.

But somehow, incredibly, Neidhart seldom neglected his training, even it it meant hitting the gym at 4:00 a.m. after a match and a grueling 500 mile bus trek through sub-zero gales.

When examined on the inevitable allegation of fakery in pro wrestling, Neidhart wanted to go on record this way: "You're invited to step into the ring against any of us at any time; we'll take on anybody. Decide afterwards if you still believe we're a bunch of clowns."

A career break hit in July, 1979, when the Oakland Raiders signed Neidhart to his second NFL contract (he is one of a very few free agents ever to sign with a second team). But a freak elbow injury sidelined him before the season began and Jim never saw any game action. Still, he was a Raider as evidenced by the lucrative weekly checks. Neidhart was re-signed after the draft then waived. At the time of this writing he's talking with other NFL general managers.

For the record, Neidhart is highly regarded as one of the five strongest men in pro football. And if it came down to an actual bench, squat, and deadlift competition, it is generally agrees among those who know that he would win it.

A firm believer in blasting the traps with nothing but heavy weight, Neidhart steadies himself in a 394-lb snatch high pull double.

Neidhart's first genuine exposure to the science of heavy weight training began the day Russ Knipp, weightlifting Olympian, sat down with the high school junior and charted an intensive workout program based on percentages.

Today, Jim swears by the concept and over the years has tailored it to his specific needs: shot putting, football, or wrestling.

His training partners have included such "heavy metal" giants as Pat Casey, George Frenn, Wayne Bouvier and former shot put world record holders Al Feuerbach and Terry Albritton.

Wayne Bouvier

Okay, enough of the foreplay, Neidhart's training schedule (for strength):

MONDAY

Bench - 5 doubles, max.

Squat - 5 singles, 5 doubles, max.

Power Clean - 10 singles, max.

Incline DB Press - 4 x 10 x 120's.

WEDNESDAY

Bench - 3x10, 75% max.

Squat - 3x10, 75% max.

Snatch High Pulls - 5 doubles, 25% over Snatch max.

FRIDAY

Bench - single lockouts, 30% above max.

Bench - 30 reps, 85% max.

Squat - 5x3, high box, 10% over max.

Power Clean - 3x10, 75% max.

Incline DB Press - 4x10, 120's.

Bench, Single Lockouts

When "the feeling is right" Jim will launch into multiple sets of Russian twists, back hyperextensions and various forms of abdominal work. Miles and sprints are run on off days.

Neidhart believes lockouts are sadly unused by everyone save the polished, competitive powerlifter.

"Lockouts are really the only way to improve your bench. You must get used to HANDLING a heavy weight before you can press it," he adds. "And don't be afraid to load the bar up."

Other tips:

- It's very important when squatting heavy to avoid taking extra steps away from the rack; one-half step is perfect. Don't let the bar clank, either. Each time the plates clank it means the pressure on your body is changing. Keep the bar perfectly controlled and silent. Open your knees, force them out, and drop straight down as relaxed as possible.

- Tuck your chin in when benching.

- Stretch continually throughout your workout. This is the key to getting full extension and actually performing the lift correctly.

- Don't wear gloves. Part of the training is toughening up the palms.

- Most people wear their belt too high. Lower it and wear it especially low on the squat and deadlift.

- How much rest between sets? Take as much rest as you need. Listen to your body and respond appropriately.

- Get your mind on competition. It's not enough to train year in and out without actually testing yourself against your peers, whether you're into lifting or bodybuilding. I've seen too many sad cases of men getting old in the weight room and leaving the contest aspect of our world outside the door.

Neidhart dismisses most Nautilus equipment saying, "Somebody is always trying to invent a machine to replace the bench press. But how can they? The human body doesn't respond to something favorably just because it is by far the single best strength builder.

Calling himself "an intense student" of weight training, Neidhart doesn't hold back on opinions or comparisons. He has stated "football players on any given level aren't close to having anywhere near the sheer athletic ability of a world class shot putter."

"To put the shot you must have tremendous "elastic explosion" but even that doesn't mean a thing without the form . . . which Feuerbach, Albritton, George Woods and Bryan Oldfield have mastered," he says. "When you look at their amazing combination of speed, strength, time and coordination, you'd have to call them the greatest athletes alive, I believe.

Neidhart termed CBS' "Strongest Man in Football" a travesty, criticizing the show's "most reps" method of determining strength. "I always thought 'strongest' meant the most anyone the most anyone could lift, not how many times someone could pump a medium weight," he added. Stating that it should have been conducted like a powerlifting meet, Neidhart nevertheless feels he would have won if asked to compete.

Strangely, the same type of snafu occurred at the original "World's Strongest Man" affair, again on CBS. Neidhart received a written verification that he had been selected a contestant along with a detailed description of the events. A month before it was scheduled for filming, a producer called with the bad news that he was out. Why did the organizers pass up Neidhart while allowing a "mind control" expert to compete?

"That's the way it goes sometimes," the producer shrugged.

Enjoy Your Lifting!