Mike Arthur's Coaching Bio (to 2019):

1976 to Present - University of Nebraska, Director of Strength and Conditioning.

1976 - World Record, 542.25 lb. Deadlift, 132 lb. class (IPF)

1995 - National Collegiate Strength and Conditioning Coach of the Year (Professional Strength and Conditioning Coaches Society.

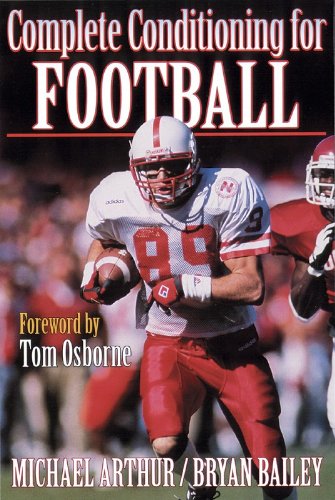

1998 - Publication of Complete Conditioning for Football.

2003 - Inducted into USA Strength and Conditioning Hall of Fame.

2018 - NSCA Impact Award.

Boyd Epley, Hall of Fame Strength Coach:

For the first 100 years of college football, almost every coach told athletes NOT to lift weights, afraid they would become muscle-bound and lose coordination. We now know that there is no faster way to improve athletic performance than through strength training and conditioning. When looking at the strength and conditioning profession today (2019), it's hard to believe that a football player at Marquette University was kicked off his college football team in 1967 because he refused to stop lifting weights after being told by his coach to stop.

On August 15, 1969, Bob Devaney, Head Football Coach at the University of Nebraska, took a chance and hired me as the first paid collegiate strength and conditioning coach. At that time, there was no in-season lifting, no summer conditioning, and no performance testing combines. Only a few athletes sprinkled across the country were lifting in basements or garages out of sight from their coaches, because coaches at the time thought lifting weights would make their athletes slower.

When Coach Devaney hired me, he said, "We're going to give lifting weights a try because Asst. Football coach Tom Osborne thinks it's a good idea, but if anyone gets slower you're fired."

Mike Arthur:

Looking back on my life and reviewing all the experiences, it now seems as if my life had a written script. Growing up in Nebraska during the fifties and sixties, I had an ambition to play football in Nebraska. When I was old enough to participate in midget football, I had one big problem. I did not weigh enough.

The cutoff limit was 100 pounds and I weighed 80. The next year, the same thing. Somehow I had to gain weight.

One day, strolling through the sports department at Montgomery Wards, I spotted a picture of Bruce Randall, a former Mr. Universe, curling a barbell.

He looked muscular, so I figured that was my ticket to putting on bodyweight. At that time, most coaches, including my dad, were not receptive to lifting weights. They believed adding excessive muscle would restrict your joint mobility and speed of movement, negatively affecting physical performance. I did not care, I was going to do whatever it took to gain weight. Furthermore, besides gaining muscle mass, the side effect of strength could only be a positive. How could it not be?

My dad reluctantly purchased the 110-pound barbell set for my Christmas present. The program that came with the barbell set only included upper body exercises. No squats, no bench presses, no power cleans. Consequently, I did not gain much weight.

Nevertheless, the veins in my forearms starting sticking out noticeably from all the curls A few months later, while at a local drug store, my eyes spotted a magazine cover of a very muscular man bending a thick piece of steel rebar.

Good grief, I know the old mags way too well. I saw these two covers in my head as soon as I read the above.

The magazine was Mr. America, published by Joe Weider [cover-man, Chuck Sipes]. Then I spotted another other muscle magazines, Iron Man, published by Peary Rader, Muscular Development, and Strength & Health, published by Bob Hoffman.

Useful information, which I could apply to my personal workouts, packed these magazines. I fervently read them all, from cover to cover numerous times, enhancing my lifting expertise in bodybuilding, powerlifting, and Olympic weightlifting.

I constructed my own lifting equipment (bench and power rack) and this subsequently led to other boys in our neighborhood training in my basement weight room. they all benefitted by building muscle and getting stronger.

Unfortunately, I did not gain much weight, but I developed phenomenal strength. I played three years of high school football but never played enough to letter. On the other hand, some of the neighborhood boys who lifted with me later made the all-state football team and played in the senior shrine bowl. That verified, in my mind, nevertheless, the positive benefits of lifting weights were irrefutable.

During the spring of 1969, I entered and won the Nebraska State Powerlifting meet at the age of 17, weighing 120 pounds. Because of my success in powerlifting, I decided to shift my focus to lifting instead of football. As destiny would have it, I saw an NFL documentary that highlighted a person named Alvin Roy. It featured him coaching the San Diego Chargers on how to lift weights. Deep inside, I knew this was my calling, the reason I was alive. I envisioned myself becoming an athletic trainer, and, as a spinoff, developing a weight training program for the football players. The combination of two fascinations that I loved, lifting and football. Alvin Roy was showing the way.

One thing led to another. I learned about a small weight room at the University of Nebraska. It was in the Schulte Fieldhouse with the purpose to rehab injured athletes. Everything was lining up with a weight room already in place. It just needed the right person (me) to implement a lifting program for the football team.

During the fall of 1969, I started sneaking workouts in at fieldhouse after school while the football team was out practicing. The room provided an Olympic bar, a bench press bench, and the squat rack needed for powerlifting. To enter the weight room, I first had to go through the training room. One afternoon, the head trainer happened to be in the training room. He noticed me entering the weight room and followed. In a snappy authoritative way, he told me that I could not lift there. As this transpired, another person approached. He told the trainer that I was Mike Arthur, state powerlifting champion, that it was okay.

I recognized this person as Boyd Epley, who I had previously witnessed as talented pole vaulter at track meets I had attended. It impressed me that he knew who I was. He informed me that Bob Devaney had recently hired him as the strength coach for the Nebraska team. I was disappointed that he beat me to the punch, but on the other hand, I sensed that Boyd was a good fit, with his physical appearance and outgoing personality. I immediately became good friends with Boyd. Nebraska football got their money's worth hiring Boyd. Football took a sudden leap forward winning the NCAA football championships in both 1970 and 1971. This quickly transformed the way football operated in a radical way and on a national level.

The belief of becoming muscle bound quickly vanished.

I enrolled at the University in the fall of 1970. I took pre-med classes, so that I could gain acceptance to physical therapy school. I never was fond of going to school and sitting in classrooms. I could not figure out the importance of Chemistry. It bored me to death, and I started skipping classes. The consequence was bad grades. After two years the university put me on academic probation. I had to take a class and get a B or better to continue my college education. That summer I took a history class and received a B+.

The next semester, I cut the number of credit hours I took so that I could get things figured out. I landed a part time job at a local health club geared towards competitive lifters and bodybuilders. I enjoyed my new job setting up programs for serious lifters and dropped out of school for one semester. The following semester I took only six hours. One of the classes I took was exercise physiology. I completely enjoyed the subject, studied rigorously and received an A. I switched majors to physical education, went back to school full time and received good grades.

Subsequently, I met a beautiful girl. Looking back, I was merely infatuated with her, but I thought it was love. We shared an apartment, and the bills started pouring in. Instead of dropping the girl, I dropped out of school. I quit my part time health club job and worked full time as a construction laborer. After about a year, we broke up.

Earning a good salary, I continued to work construction. During the summer of 1976, I was offered a job at University of Oregon, not as a strength coach, but as a construction laborer to help build dormitories. The pay increase was substantial, so I decided to go. Before leaving, I stopped by the weight room to say goodbye to Boyd. He told me that I was making a serious mistake; instead, I should finish my degree. He added, when I received my degree, he would hire me as his assistant. This definitely caught my attention, but I felt obliged to go to Oregon. But I told him I would think about it.

I went home and thought it over. After taking exercise physiology, I saw two drawbacks related to strength training. (Note: Boyd Epley deliberately used the phrase strength training to differentiate from competitive lifting, bodybuilding and weight training for fitness.)

First, the lack of strength research; though a limited number of scientists were conducting strength research, the unscientific acceptance of the condition known as "muscle bound" was still prevalent.

Second, the muscle magazines covered the only worthwhile programming information, which did not relate to the strength training of football players. There was a gigantic gap between strength research and the practical application of strength science for football players. I wanted to bridge the gap I observed between science and strength application. I met with Boyd and told him I did not want to spend all my time in the weight room. Instead, I wanted to devote some time to keeping up to date with strength and conditioning research and then develop training systems and methodologies based on new scientific insights. Boyd responded positively. Without any hesitation, "OK."

During the summer of 1978, just before I graduated, the first NSCA convention was held under the guidance of Boyd Epley in Lincoln. It seemed like a reunion of sorts, of a team called the Lincoln Lifters. Going back to the summer of 1969, three former Lincoln Lifters teammates and I had taken a trip to Denver to participate in regional powerlifting competition. I reflected how incredible it was that this trio of former teammates influenced the strength conditioning profession.

In the spring of 1978, Jim Williams, who at that time was the strength coach at the University of Wyoming, and Pete Martinelli, strength coach at the University of New Mexico, discussed the possibility of a strength coach convention. They decided Boyd had the resources and the know how to pull it off, so Jim called Boyd with the idea. I happened to be at Boyd's house when he got the call. Boyd and I discussed all of the potential outcomes, and that night the NCSA became a vision of strength training in the future.

Tom Baechle was the chair of the physical education department at Creighton University. He developed the certification examination for strength and conditioning specialists. Tom also organized several experts to write chapters providing the most up to date information and cutting edge material in strength training in the book "Essentials of Strength Training and Conditioning." Tom also recommended me to Human Kinetics, to write the book, "Complete Conditioning for Football."

Ken Kontor was hired by NCSA in August 1978, as Assistant Executive Director, and eventually named Executive Director in 1983 to run the NSCA office. Ken was instrumental in publishing the Strength and Conditioning Journal providing the much-needed unbiased practical application of cutting edge strength and conditioning.

Later, with the assistance of William Kraemer, published the peer-reviewed Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, to "bridge the gap" from the scientist to the strength specialist.

The NSCA is now the world leader in sports conditioning, with over 45,000 members.

Looking back to the first days of the NSCA, I have a bone to pick, because I experienced the time when most coaches scorned strength training. Reading what many strength coaches and sports scientists are writing today, the consensus is that the Soviet Union invented modern sports training. I disagree, though being a baby boomer who grew up during the height of the cold war might have something to do with it. From the American football point of view, training today consists of many components that prepare the athlete, divided between the football coach (fundamentals, strategies, formations, and plays), athletic training staff (injury rehabilitation), the strength and conditioning coach (physical readiness), and, most recently, the sports nutritionist (energy needs). The acceptance and implementation of strength training was the paradigm shift, not the Soviet Union's theory of sports training. Strength training made the single, most positive contribution in developing the size and speed of football players, and later affected how other sports trained, especially where optimal power is essential.

Soviet material started to surface in the late /70s and early '80s. At that time, Soviet information written by scientists and sports coaches was more theoretical than scientific or practical and did not make much sense to me. There was nothing relevant to training football players. One concept used by the Soviets was periodization, a common term among strength coaches, but an expression scarcely used by American sports coaches, and sports writers have no idea what it means.

To me, periodization was just a word for an annual plan where periods represent seasons. Strength coaches began using the term back in 1982, after John Garhammer and Mike Stone popularized it in the NSCA Strength and Conditioning Journal. I am not saying that I did not learn something from the article, I learned a lot. John and Mike took a serious theory, related it to the "General Adaptation Syndrome," scientifically researched it, and rendered it into a simplified plan of action.

They put out plenty. Here's one:

We must remember that the Soviets primarily train athletes involved in individual sports (Olympic weightlifters), where the goal is to peak for world or Olympic competitions. This does not apply very well to football, where athletes must report to fall camp in top condition and maintain endurance and strength levels for the entire season. They cannot physically peak as the season progresses to win the bowl game at the end of the year. The teaching of specific game fundamentals, learning plays and gaining experience during the course of the season are primary, strength and conditioning, though extremely essential, is secondary. The planning is different in an essential way.

The trademarks of Boyd's programming were detailed planning, a git 'r done attitude, and the ability to adjust the plan as needed. He definitely had an annual training plan, with conditioning objectives for each season. Here is a passage from one of the first manuals he wrote in 1972.

"The University of Nebraska has developed a year-round program for all sports with specific training programs for different periods of the year."

Boyd adjusted his program to how football coaches prepared by breaking the year down into seasons. Football coaches, long ago, instinctively had the basics of periodization in place, meticulously planning every detail.

Here is my short-history version on how this paradigm shift took place:

Thomas DeLorme, an American doctor, rehabbed injured soldiers after World War II and demonstrated the benefits of weight training. He coined the term "progressive overload" in 1945. Athletic trainers were the first to make weight training acceptable purely as a method of rehabilitation.

It was around this time that bold individuals understood the importance of strength and began to weight train. American shot putter Parry O'Brien

included strength training as a major part of his training. He became the first to throw over 60 feet in 1954. Consider that the 50 feet barrier was done in 1912 and it took 42 years to got over 60 feet. 13 years later in 1967, over 50 men topped 60 feet and Randy Matson broke the 70-foot barrier.

"This means that weightlifting for shot putting success almost seems to be an end in itself, lifting for its own sake." Joe Henderson, "Weight Training Yields Power," Track and Field News, 1969).

Alvin Roy, in 1954, began strength training with a high school team that went undefeated and won the state championship in Louisiana. In 1958, the LSU football team won the National Championship with Alvin's help. In 1963, he helped the San Diego Chargers win the AFL Championship. His prize athlete was Billy Cannon, 1959 Heisman Trophy winner and first pick in the 1960 NFL draft.

With Alvin Roy showing the way, and the hiring of Boyd Epley in 1969, along with the formation of the NSCA, strength training reached a tipping point. Boyd came along at the right time and responded to the opportunity.

"The paradigm shift from an athletic world with only a few isolated barbell men, to a professional organization (NSCA) of strength coaches with national reach happened suddenly, and the reason for that shift is best encapsulated in five words:

Enough said, back to my story.

I finally graduated in August of 1978. I was so glad to get that behind me. I had my degree, and now I was the first paid full-time collegiate assistant strength coach. A dream come true, the script was playing itself out. I never continued my education, though that does not mean I quit learning. '

I consider strength training an art, and science as the foremost tool. It seems as I come to gain a better understanding of strength training the more questions I have. Look how complicated strength coaching is today. We now have incredible investments of time and money spent collecting and analyzing data in an effort to predict how athletes will respond to the demands of sport performance.

The perpetual search for the next paradigm shift continues.

Enjoy Your Lifting!

No comments:

Post a Comment