Here is an excerpt from "The Glenn Pendlay Method"

Thanks to Blaise for this!

EMOMS

EMOM sets are a perfect solution for effective, high-performance training. In fact, when performed correctly, EMOM sets provide better technical practice than doing singles with your max, using as much technical mastery as you can muster. EMOMs by Glenn Pendlay.

The EMOM, or 'every minute on the minute' is a method of training with which Glenn saw great benefit. An EMOM is essentially a style of training that spreads out the workload of an exercise evenly across a period of time. For Glenn, this was one single repetition every minute.

He began doing them in the 1990s, over a decade before the term was popularized by CrossFit. It was from Louie Simmons, who was using timed sets for his dynamic effort strength sessions, that Glenn discovered the idea, and applied it specifically to the competitive lifts. Though their initial use was for increasing training density and maintaining barbell velocity through the use of fewer repetitions per set and more sets per exercise, Glenn found them to be particularly useful at building technical ability in the snatch and the clean and jerk.

Technical Improvements

Though performing six triples in the snatch at 75% equates to the same volume and average intensity as performing an 18-minute EMOM, the technical transfer is less. When an athlete performs upwards of one repetition in the snatch per set they incur a certain amount of fatigue from the previous repetition. By the third repetition usually the fatigue is relatively high, and very often the technique is significantly worse than the first.

With sets of 3 in such technical lifts, Glenn noted that the first repetition was often technically the best, the second was slightly worse, and the third required a 'save' or a 'step out'.

Six sets of three therefore often boils down to six technically desirable repetitions, six reasonable repetitions an six poor repetitions.

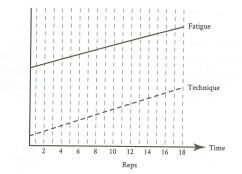

Fatigue builds quickly during each set and then drops off afterwards, rarely reaching the baseline level of the previous set. Because technique can have an inverse relationship with fatigue when fatigue is dosed too high, this means that in conjunction with the stepwise increases in fatigue, so too will there be a stepwise decrease in technique, often with the final set of the six the least desirable, and the last repetition the least similar to ideal technique.

An interesting change to the relationship between fatigue and technique occurs with EMOMs. Because there are no dramatic spikes in fatigue due to the evenly spread workload of one repetition each minute for eighteen minutes, there are no spikes in technical drop-off. Glenn noticed that not only did technique not trend downwards, it actually improved over the course of a workout, with the final repetition almost always looking better than the first.

Fatigue and Technique Over Eighteen EMOM Reps

As fatigue builds much more linearly over a workout, Glenn identified small, but positive, changes to the following?

- Rhythm of the pull

- Straightness of the bar part

- Speed of the pull under

- Depth of the catch

It was as though the internal feedback of the previous repetition was still strong enough after less than a minute of rest, in addition to the relatively low fatigue, that it could dictate positive improvements to the subsequent repetition, building in magnitude across eighteen repetitions.

'You slowly become able to catch a little bit lower, to change directions a little bit faster when going from pulling to going under, and to use a line of pull that puts the bar overhead just a little bit easier.'

- "Structuring the Training Week" by Glenn Pendlay.

The technical improvement seen from repetition to repetition during an EMOM is so great that athletes can add weight to the barbell towards the end of the workout, even setting new personal bests despite their fatigue being relatively high due to the density of the training. Incremental improvements in the four qualities above counteract the increase in fatigue, building in magnitude along with the fatigue.

Weight versus Skill

Generally in sport there is an inverse relationship between the technical and physical demands of a movement, as well as between the physical demands of a movement and the frequency with which it can be trained. All of which is to say that the more physically demanding a movement, the greater the length of time needed between bouts of practice.

At either extreme of this spectrum are powerlifters and dart players. A deadlift is, for all intents and purposes, a relatively simple movement to acquire to a reasonable level of proficiency, but it is also incredibly physically demanding, perhaps as demanding as any movement that a human could fill five seconds of their time with. Though some powerlifters might argue that the technique of a deadlift is something that is honed over an entire career, let's put it this way; the technique of someone's deadlift is not the greatest predictor of their success in the sport, strength is.

Those at the top will have both the greatest strength and the best technique, but it is strength that the majority of training time is dedicated towards.

On the other hand, dart players spend the majority of their time focused on their technique. It isn't physical capacity that separates them, it is technique. Because the percentage of time dedicated towards technique is so high, the frequency of exposure is also incredibly high.

For a powerlifter, however, the time dedicated directly towards deadlift technique as opposed to deadlift strength is so low that the frequency of exposure is significantly less.

The technical demands of the deadlift are so low that some powerlifters only train the movement once a week, some even every two weeks. Not only is this because the movement is so stressful to the body, but also because the magnitude of internal feedback of the movement is so great, as are the physiological changes, that the decay over a week does not remove the powerlifter's ability to remember how to lift a heavy weight.

A darts player, however, receives significantly less internal feedback, both from a technical and physiological standpoint, from one throw of a dart than a powerlifter does from one heavy deadlift, and so they much perform a far greater number of repetitions in order to make impactful changes. Fortunately, because they dedicate so much time to a less physically demanding sport, they are therefore capable of just that.

A powerlifter can become world class in the deadlift from as few as twenty working repetitions per week. They receive enough skill acquisition and physiological stress to improve. A darts player who relies purely on skill acquisition, however, would barely improve from twenty throws of a dart per week, regardless of how they spread it out. This is because the internal feedback of an individual repetition is far too low. Instead, a professional darts player will practice for up to eight hours a day, practicing with thousands of repetitions per week.

The snatch and the clean and jerk are different.

They are technically demanding as well as fatiguing.

Though not as technically demanding as darts or as fatiguing as deadlifts, a substantial amount of training is dedicated to strength as well as technique in order to improve the competitive lifts. The fatigue is great enough that it can reduce the motor quality to such an extent that the following repetitions can be missed, but also technically demanding enough that infrequent practice can result in missing repetitions even with amply physical strength.

A deadlift, however, is rarely missed due to infrequent exposure to the movement, and a dart throw is rarely missed due to the fatigue of the previous repetition.

Internal Feedback versus Fatigue

'As sets progress on and fatigue builds, the antagonistic muscle groups shut off more completely, which increases flexibility and makes it easier to get under the bar.' - "EMOMs" by Glenn Pendlay.

Internal feedback relates to the cues given to you by the barbell during a repetition, rather than externally, by a coach or teammate. When snatching a barbell it is very clear internally at which point during the pull, for example, your weight is being pulled too far forwards. This internal feedback is vital, and for the more advanced athlete it can provide information in a way that a coach simply cannot due to the microscopic error corrections that now characterize training. Once your body starts providing you with small cues it is beneficial to repeat the movement as soon as possible before the feedback fades.

The issue in weightlifting comes because at the point when the internal feedback is at its highest -- directly after a lift -- so too is fatigue. Depending on the intensity of the repetition or the time under tension of the set, the fatigue will be at differing magnitudes, requiring different amounts of time to recover before the internal feedback can be used by repeating the repetition to a higher standard than the last.

Let's look at darts again as an example.

The fatigue build up by throwing a single dart is incredibly low, but the feedback from throw to throw is incredibly high. If you feel your arm pull in medially upon release and you can observe the dart landing an inch further to the left then you can not only deduce that you need a straighter finish, but you actually know how it should feel based on the previous repetition, such that you wouldn't even need to look at the dartboard to know if it's a good throw or not. Due to the lack of fatigue the darts player can use the internal feedback while it is at its peak, immediately after the first throw, and improve.

Imagine the following example. A darts player can throw ten darts. They can either throw one dart ever five minutes for fifty minutes, or every 10 seconds for a hundred seconds. The one who throws every ten seconds will have a more perfect final throw than the person who waited for five minutes in between repetitions because they were able to use the internal feedback while it was at its peak. After five minutes, that internal feedback might all be gone.

Fortunately for weightlifters, the internal feedback from a snatch or a clean is of greater magnitude than from a throw of a dart due to the stress of the movement, and as a result has a longer half life. As technical as we might believe the snatch is, it doesn't compare to how fine a correction a darts player might make, unlike the gross movement changes from a weightlifter.

Of course we cannot speak about the competitive lifts as a monolith. A 90% snatch is very different from a 405 snatch in terms of the internal feedback it provides us with and the fatigue that it leaves us with. Though a 40% snatch provided us with less internal feedback than a 90% snatch, it produces very little fatigue, and so it can be repeated five or so times with each successive repetition looking better than the last. An 80% set of five in the snatch would produce more internal feedback per repetition but also significantly more fatigue pre repetition, such that each repetition would look worse from a technical standpoint than the one that preceded it. At which percentage of a one repetition maximum it becomes most technically beneficial to switch from triples and doubles and move towards singles, placed within a minute of the last, I do not know. Glenn, however, believed that this was at the 70% range, because it was here that he would begin programming EMOMs, right the way up to 80-85%

Usable Feedback -- EMOMs

'Performing EMOM sets trains the body to fire motor units faster, more explosively and more powerfully, and then turn them off quickly, which is the holy grail in sports.' "EMOMs" by Glenn Pendlay

It is worth acknowledging that Glenn never spoke about useable feedback. In fact, to my knowledge, he never spoke about the EMOM in any way beyond the explanation that fatigue builds so slowly over a workout that the technique of each repetition is improved.

The following is a model of my own, used to explain what Glenn did in a way that hopefully sheds more light on why it worked:

As mentioned previously, after each repetition of a snatch and/or clean and jerk, the internal feedback is immediately at its highest, trending towards zero over the following few minutes. The length of time depends on the stress of a set. The internal feedback from a 40% single would decay far more quickly than from a 90% single.

Fatigue and feedback both decay exponentially, but the decay of fatigue drops less each subsequent second, and the internal feedback drops more each subsequent second. This means that there is a point at which the fatigue has dropped substantially more than the internal feedback, providing an optimal point at which to perform the following set. This would be the peak on a new line that could be called 'useable feedback'.

Immediately after a repetition in the snatch between 70-85%, it makes sense, based on Glenn's own programming, that he believed that although the internal feedback was highest, the repetition was unreplicable due to the fatigue of the repetition being high. As such the usable feedback is not at its apex.

After roughly sixty seconds the difference between the fatigue and the internal feedback is at its greatest, and so the usable is not at its apex (see graph below).

Glenn had no scientific proof of the time frame other than through practice, but to him it seemed that sixty seconds was ideal. Beyond 85% EMOMs become less productive. The fatigue from each repetition requires more than sixty seconds of rest before it can be replicated with ideal technique. Fortunately the feedback remains for longer too. As a result 90%+ lifts were trained in a different way.

The EMOM model provided the optimal way to train effectively between 70% and 85% of 1RM.

Though Glenn never explained the benefits of the EMOM in such a way, I believe that this was the underlying rationale for their use. When you take his view that technique is improved rep by rep due to the gradual increase in fatigue, rather than the large increases brought on by heavier triples, it seems that this concept of internal feedback versus usable internal feedback as manipulated by fatigue makes sense.

He regularly mentioned that during EMOMs his athletes would move faster, pull straighter and catch deeper, and I believe this is because he found the perfect length of time at the correct intensities to use the internal feedback of each repetition optimally.

Just as the darts player throws every ten seconds and the powerlifters deadlifts every five minutes, the weightlifter snatches every minute on the minute.

Exceptions

Do not mistake Glenn's love of EMOMs for a removal of all multi-repetition sets in the competitive lifts. They were used as a way to optimally build technique more broadly without using specifically targeted variations. They weren't used during all periods of training however.

There are periods of a competition where stamina is a priority, or where an ability to recover and produce fine motor movements is important. As a result, EMOMs were generally programmed towards the middle of a full training cycle.

The first month might include sets of two or three repetitions, occasionally even five, sometimes of hang variation. This would improve the athlete's work and recoverable capacity.

The following month might use EMOMs, a way to focus on honing in on better technique for the single as performed in competition, while also ramping up average intensity.

The last month might use up and downs (see next chapter) in order to improve the technique specifically for high intensity singles

How to Implement EMOMs

'I put EMOMs on Monday for a symbolic reason. The snatch and the clean and jerk are what weightlifting is all about . . . we are always going to be performing the competition movements exactly as they are done in competition.' - "Westside for Weightlifting" by Glenn Pendlay.

EMOMs are always implemented on a Monday the high volume, moderate intensity weightlifting day. They fit well into the intensity and volume allocation of a Monday, as well as prioritizing the most important part of weightlifting. Another important reason for the placement of EMOMs on a Monday is that they produce very little muscle soreness, and as a result they do not impact the following days of training in the same way that starting off the week with 5 x 5 back squats would.

Glenn used a pendulum-like wave to program his EMOMs, from 70% on week 1 to 80% on week 3. Occasionally there would be a week 4 at 85%, but usually the Monday EMOM increased over a three week period from 70% to 80%. As the percentage increased over the three weeks the required volume would decrease. Volume was also dedicated by categorization as follows:

It was always written into each EMOM that after making the first half of the repetitions you were allowed, or even advised, to add weight per set, so long as 90% of the previous repetitions had been successfully made.

So, for example, during week 1 an intermediate athlete might perform ten repetitions at 70% over a ten minute period, before adding a couple of kilos each rep until they hit a maximum for the day of around 90%. Sometimes they might add weight up to only 80% and stay there. It depended on how they were feeling for the day.

Snatch and clean and jerk EMOMs would be programmed one after the other on a Monday. With up to 48 repetitions between the two movements in as little as 48 minutes, EMOMs can be an extremely difficult way of training.

Mental Benefits

'In short, it keeps your head out of your ass because it doesn't leave you enough time to get it up there.' "On the Minute Training for Weightlifting" by Greg Everett.

The monotonous routine of the EMOM allows the weightlifter to get into a very repetitive rhythm. With only a minute in which to successfully execute a repetition and rest for the following one, there is little time to worry. Most weightlifters finish the repetition with forty to fifty seconds to spare, and then by the time they have sat down and caught their breath they have little tome to become overly emotional about the next repetition. Instead, they become more robotic lifting on cue like a metronome, making small technical changes over the course of the workout. For athletes who get in their own head and experience paralysis by analysis, the EMOM is a brilliant way to bring them to a more present and focused way of lifting.

Glenn believed that weightlifters need to train with heavy snatches and clean and jerks in order to make the best technical improvements. The issue is that you cannot perform multiple 95% snatches every session. Glenn called this 'the weightlifter's dilemma'. EMOMs build fatigue, as well s the speed, pull and depth afforded by 70-80% weights.

Enjoy Your Lifting!

No comments:

Post a Comment