Hollywood Star and Idol of Millions Bill "Peanuts" West

Photo Courtesy of Lydia Tack

This Article Courtesy of Liam Tweed

Thanks Again, Brother!

1955

Doug Hepburn Says:

"A 400 Pound Clean and Press is Possible . . .

And I'll Do It!"

by Charles A. Smith (1954)

When Arnold Luhaar of Estonia made the highest clean and jerk of the 1936 Olympics with a poundage of 363, the occasion was cause for applause. And when he created a new world record with 369.3 pounds, way back in 1937, the World of Weights went haywire over the strength of the 5 foot 10, 264 pound Powerhouse from the Baltic.

Arnold Luhaar

In those days, feats performed by Luhaar were indeed remarkable. So much so, if anyone had forecast that in the future, well within the lifetime of most fans who had witnessed the lifting at Berlin, a man would come out of obscurity and use that record weight for Repetition Presses, certain gentlemen in white coats would have been promptly called for, and the local mental institution would have had a brand new inmate.

In fact, a much more sensible prognostication would have been, "One day they'll run the hundred yards in 5 seconds." So impossible of achievement did even a single clean and press with 390 pounds appear.

Even two years ago, the suggestion that a man would one day be close to a 400 pound clean and press would have called forth the usual "Are you kidding?" or "Yes . . . when nannygoats play the bagpipes."

Only four men in weightlifting have ever officially cleaned and jerked 400 or above . . . Rigoulot . . . Davis . . . Schemansky . . . Anderson. And since weightlifting fans fully appreciate the power it takes to make such a lift, the magnitude of its effort, the skill, speed and timing required, they might well be excused their skepticism. I say that there is a man who will create a 400 clean and press record and in the not too distant future. His name? The present World's heavyweight Lifting Champion and World's Strongest Man, Doug Hepburn of Vancouver.

It is hard for any beginner to appreciate what it takes to make such a lift. The best way to learn is to try and dead lift this poundage off the floor, and pull a muscle or two. After the novice has made this experiment, he'll not only respect the men who can clean and jerk 400 but he'll realize how fantastic is the power of a man who has already pressed more than this weight from the shoulders. He'll also wonder how on earth any mortal man can raise such a load of iron overhead.

The lifter or bodybuilder of experience, knowing more about the power of the Old Timers, will respect any man who can perform a 400 pound clean and jerk since he knows that the fabulous greats of the Iron Game, Goerner, Saxon, Cyr, Swoboda, Apollon, men who were among the strongest of all time, never were able to clean and jerk 400 pounds. Not that they didn't have the power; the lacked science and our modern training methods. It is also possible that type of equipment used made a difference to what they could have lifted.

Charles Rigoulot

Apollon The Mighty (Louis Uni)

But with the press from the shoulders, just sheer power is required, the only section of he lift demanding skill or technique, being the clean. Now Doug Hepburn has always possessed the unusual ability to press whatever he could get to the shoulders. In other words, what he can press according to Olympic lifting rules is limited to what he is able clean. While this might seem a tremendous physical superiority, yet actually it was a disadvantage which I had to help him beat when I first began to train and teach him Quick Lifting. Let us see why it constituted a handicap.

Doug at one time actually disliked the quick lifts because he felt that together with his physical handicap they presented an obstacle he could never climb over. This gradually built up in his mind a negative attitude to snatching and cleaning, a feeling of defeat which made even the thought of training on them somewhat distasteful, yet alone entertaining any ideas of improvement.

Doug realizes now of course that his attitude was wrong, that the real reason behind his dislike was very obvious, because he was poor in snatching and cleaning, and so considered himself ill-suited to quick lifting. While it is also true that Doug's physical handicap has somewhat restricted his lifting advances, his outlook has so changed that he now enjoys training on the quick lifts, and if he continues to make advances hopes to be able to break the great record total set by John Davis, the man he admires so much.

Once the dislike of the quick lifts was overcome, with the help of my coaching, which incidentally did not begin at the World's championships but started way back in 1950, he made steady advances; so did his ambition rise and he began to think more and more in terms of not merely pressing 400, but of cleaning it and pressing it.

There is no doubt that Doug's extraordinary deltoid and triceps power, coupled with extremely favorable leverages, led him to concentrate more on pressing feats than on competition lifting. While he was able to improve his press, he had no thoughts of training for Olympic lifting or even entering competition. As soon as his snatch and clean began to improve in power and technique, it not only served to boost his actual clean and press record bit it made him realize what his actual strength potentials were. So far as he is now concerned, the sky is the limit.

The ambition of the World's strongest man to press 400 pounds was first realized at the Metropolitan AAU's annual Mr. Eastern America show, run for fundraising purposes by Joe Weider. There Doug pressed the colossal poundage of 410 . . . pressed the weight mark you, not jerked it, after the bar had been lifted into position at the shoulders.

Since this time, so marked has Doug's improvement been on the clean that he has three times broken the worlds clean and press record, once at the Junior Nationals with a poundage of 366.75. Again shortly after during a special tryout for the Canadian AAU with 370, and once more at the World's Championships in Stockholm with 371.5. His best clean stands at 385 and is still showing signs of improvement. Even with a badly injured knee, and his club foot, Doug still beat the greatest collection of heavyweight lifters ever to appear on a platform.

How the World's Strongest Man is Training for a 400 Pound Clean and Press

Since the most important part of the lift for Doug is the clean, he is devoting almost two-thirds of his training time to that section. The rest of the time he spends practicing movements that will assist the press.

Note: Doug became something of a Clean and Press specialist at this point. Many men for many decades specialized on their favored lifts, so the Bench specialists of today are certainly in good company, and deserving of the same respect given all who set groundbreaking records.

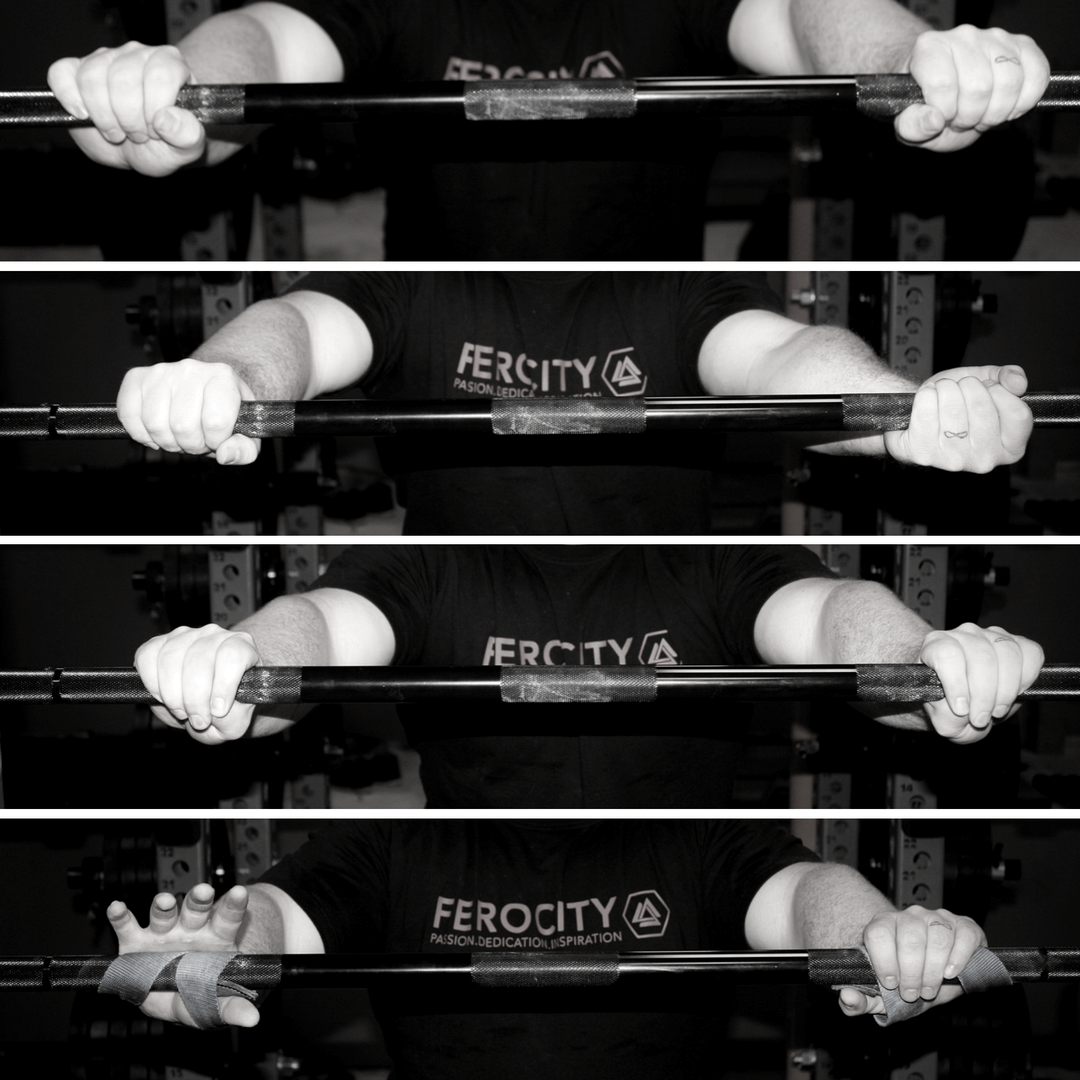

Doug commenced with the clean, using a comparatively light poundage for a warm up, and also to perfect his form. Starting off with 270 for 5 repetitions, he jumps 20 to 30 pounds at a time until he is using 360. with his second warm up weight, around 290, he does 3 reps, then 300 x 2, 320 x 2, 340 x 2 and finally 360 x 2, which is his training weight.

The World's strongest man has always believed that in order to increase strength the heaviest weights must be handled as often as possible. With the 360 he strives to do as many sets of 2 reps as he can, aiming for 8 sets of 2. As soon as he gets the 8 x 2 with 360, he increases the weight, again working up to 8 sets of 2. The first clean is made from the floor, the second from the hang.

After the cleans are finished Doug rests up for 15 to 20 minutes, then starts his press training. Contrary to the usual practice he does not perform standing presses but sticks to bench presses off the chest. He has found that this movement is more than sufficient to increase overhead pressing if performed correctly, without the arch of back and bounce off the chest.

But there is another and equally important reason for not performing standing press after a strenuous session of cleans. It way my opinion that the lower back muscles would be subjected to plenty of work by the hang clean .Standing presses place a lot of strain on the lower back, especially during the final stages of the press training when each individual lift is hard and there is a tendency to use a slight back bend.

It is then that there is a strenuous contraction of the muscle groups in the lower lumbar region as they act an effort to maintain an upright position of the trunk. The work entailed in cleaning the bar, not only for actual clean improvement, but also in cleaning for the standing press, might easily cause a condition of staleness and fatigue, and thus hinder or eliminate any gains made.

It was a theory that had to be proved and Doug decided to take the risk when he started to train for the Junior Nationals, and subsequently for the World's championships. So he just cleaned for clean improvement, then used the bench press off the chest to boost the power of his standing press. Once every two weeks I had him set aside a special day on which he would make his limit attempts for the standing press and nothing else.

At the Junior Nationals the theory was proved a resounding success. Doug smashed three Junior National records, one of which was also a new World record, the clean and press with a poundage of 366.25, and as mentioned before in this article, he subsequently went on to smash the world clean and press record twice, in addition to capturing the World title.

Now that you have the schedule of the World's strongest man for improving the clean, let's see how he goes about maintaining his pressing power. Since we already know that Doug relies on the bench press to preserve and increase his strength in the standing press and why he does so, let us examine his system of sets and repetitions.

As in the clean, not only does Doug believe in using the heaviest possible poundages but also in thoroughly warming up. First he uses a light poundage of 300, or a little above, for 5 reps. Then he increases the weight 20 or 30 pounds for a secondary warm up, and again for a third warm up. Then he jumps into his regular training poundage which he uses for 6 sets of 3 reps. The poundage he is using at the moment is 430 pounds. It has been with this bench press routine that Doug has recently pushed the record up to 560 pounds, and his one hand military press to 195 pounds.

The end of the workout comes with heavy squats, a movement which Doug feels every lifter should include in his routine. It is a developer of basic body power, and no matter how much the arm chair scientists of our sport sneer at it, it is the exercise which has enabled so many famous lifters to make steady Olympic lifting advances, men like John Davis. Danny Uhalde, Tommy Kono, Paul Anderson, and of course Doug himself. He does 5 sets of 5 with 560 pounds, going all the way down, not just upper thighs parallel to the floor.

This is the routine the World's strongest man and Olympic lifting champion is using to reach a 400 pound clean and press. Will he do it? There is no doubt in my mind that he will. How soon remains to be seen but I feel it will be some time in 1954, perhaps at the British Empire Games to be held in Vancouver, Canada, in July.

Recent advances Doug has made speak for themselves. They include the lifts mentioned above, and a 470 pound press jerk. He is aiming for a 600 pound bench press and feels that when he reaches this figure he will be capable of a 500 press jerk, a 450 press from the shoulders and . . . the record he is now so strictly in training for . . . a two hands clean and press with 400 pounds, a record which only another giant of strength, such as Doug is, will be able to approach, perhaps beat.