Related Material by Pavel:

Super Joints -

Relax Into Strength -

Beyond Stretching -

Beyond Stretching: The Seminar -

Loaded Stretching -

Strength Stretching - For a Bigger Squat, Bench & Deadlift -

https://www.amazon.de/Strength-Stretching-Pavel-Bigger-Deadlift/dp/B004JPT1MK

Main Site:

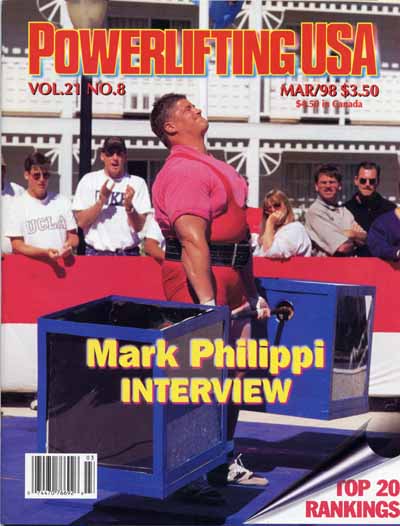

Originally Published in This Issue - March 1998

Pavel Tsatsouline: The Evil Russian

as told to Judd Biasiotto, Ph.D (1998)

Despite the fact that there is a prolific amount of research which clearly indicates that flexibility will not only decrease injuries but enhance athletic performance, very few athletes engage in flexibility training. It's been estimated that less than 20% of the competitive athletes in America are engaged in such training. Even more discouraging is the fact that most athletes who do stretch are not doing it correctly.

Shocked into awareness many coaches have undertaken the chore of establishing a "science of flexibility" - a consistent, systematic methodology that would enable an athlete to increase his suppleness and muscular power - a labor which has not reaped conspicuous dividends, but there is a light in all the darkness . . .

The foremost authority, critic, and writer in this emerging body of knowledge is a Russian physiologist, Pavel Tsatsouline. His recent book, "Beyond Stretching: Russian Flexibility Breakthroughs" is without question the definitive text on the subject. It is MUST READING for every athlete.

For a powerlifter it could mean the difference between being good or great. I'm serious; the information in the text is that significant. It is scholarship that is extremely esoteric.

Tsatsouline's authority springs partly from personal experience. Raised in Latvia of Russian parentage, Pavel got interested in flexibility training when he took up kick boxing. His parents were very encouraging. Pavel's father, Vladimir, is a retired Soviet Army officer and a passionate athlete. Swimming, boxing, judo, skiing, running, fencing, you name it, he's done it. Pavel's mother Ella is a former professional ballerina. When she was a kid studying at a ballet school, she was the most feared street-fighter in the neighborhood. Ella would deal out quick justice to the local punks with rapid-fire kicks in the face, years before karate was introduced to Europe and America.

Pavel Tsatsouline studied English at the Institute of Foreign Language in Minsk, Belarus (in what used to be the USSR) before receiving a degree in coaching and sports physiology at from the Physical Culture Institute (IFK). He served as physical training instructor for close to two years in Spetsnaz, with the Soviet Special Operation Forces. In Spetsnaz, he did his time near Moscow and in the Artic, in the diversionary reconnaissance detachment of the Red Banner Northern Fleet. Having to fight three or four men with your hands tied behind your back as a part of hand to hand combat training encouraged good flexibility.

"I have trained Soviet commandos to do splits in three to six months - whether they wanted to or not," quips Tsatsouline. "Now, that I have turned into a capitalist running dog, I can teach Americans how to stretch too. When I'm done with you, you will have the flexibility of a mutant. Or else." Yes! He is extremely humorous, but he is also eminently confident. Talking with him it is evident that he is a man who believes in himself and what he is doing.

Tsatsouline is not exactly a slouch as an athlete either. He started lifting weights to get stronger for fighting, but got the iron bug and eventually earned a National ranking of Master of Sports in kettlebell lifting, an ethnic Russian sport where you lift these big metal balls with handles for reps (this was written in 1998 . . . how different this is now!) I have witnessed such competition - it takes a MAN!

Still, it is his brain, not his brawn, that is most impressive. In my opinion it won't be long before he revolutionizes the field of flexibility. "Most Western flexibility experts," Tsatsouline states, "do not know enough physiology to have sex. You are far better off not stretching at all than following their advice. I'll fix it." I'm convinced Pavel Tsatsouline will do just that.

What follows is a two part (second part in another post to follow) exclusive Powerlifting USA interview on the subject of . . . .

Dr. Judd: Let's start by defining our terms. What precisely is flexibility?

Pavel: In athletic terms, it's the ability to perform your sports techniques through the required range of motion efficiently and without joint stress.

Dr. Judd: I once said that it would probably be easier to find a legitimate television evangelist than a powerlifter who can touch his toes without bending his knees. Isn't the lack of flexibility a major problem for powerlifters?

Pavel: Hell, no. When you stretch, you desensitize your stretch reflex. This reflex is what puts a 'spring' into your movement. A muscle that has been sharply stretched generates more force than a static muscle. To appreciate the difference try pitching a baseball without a windup or squatting from the low pin in the power rack. When you become more flexible, the muscle has to be stretched further and faster before the stretch reflex fires, or rather sizzles. As a result, you have to do most of the lifting on your own steam, without the extra boost of a reflex contraction.

Dr. Judd: That's interesting because most old-timers instinctively avoided stretching, feeling that they could lift more weight if they stayed "tight."

Pavel: They were right, up to a point. Why do you think Russian Olympic weightlifters avoid exercises that promote excessive flexibility of the muscles surrounding the hip and knee joints? Too much flexibility there makes the lifter sink too deep when he is getting under the weight. The same is true in powerlifting. You do not get extra points for squatting ass to the floor.

Dr. Judd: What if a lifter can't squat deep enough?

Pavel: I designed a special stretch for that. After I showed it to 900-lb squatter, Dr. Fred Clary . . .

. . . many lifters from the Twin Cities Gym in St. Paul, Minnesota, picked up on it. Hold a light barbell, 95 to 135 pounds, over your head in the position for the press behind neck lockout.

Inhale as deep as possible and tighten up every muscle in your body. Squat as deep as you can, making sure the bar stays behind your neck overhead, your weight is on your heels, and your knees do not buckle in. Hold your breath and tension for a few seconds, then suddenly exhale, letting all the tension go with that breath of relief. Your hips will sink an inch or two. Make a point of maintaining the alignment described earlier. Inhale and tighten up again and repeat the drill. Do the stretch inside a power rack with the pins set high, so you do not fall on your butt, but rather hand on the bar if you lose balance and fall.

Dr. Judd: Why not hold the bar on your back?

Pavel: It's too easy to cheat by bending over and rounding your back. When the bar is overhead, you are forced to keep the arch and stay upright!

Dr. Judd: Why the unusual breathing pattern?

Pavel: There is a relationship between muscular tension and your breathing patterns, the pneumo-muscular reflex. Lifters take advantage of it unknowingly. They increase their muscular tension by inhaling to the hilt before the attempt. In stretches we use the reflex to relax the muscles beyond what could be achieved by just 'ordering' them to relax.

Dr. Judd: Would excessive flexibility negatively affect the other two powerlifts?

Pavel: You bet. In the bench you will not be able to effectively store the elastic energy from the descent for the ascent. You might as well press from a dead stop in the power rack! Also, you might get red-lighted. For the same reason - the inability to keep the tension - the bar is likely to sink into your chest during the pause.

Dr. Judd: And the deadlift?

Pavel: If you are too flexible, you will lack tension at the start of the pull. That will limit your poundage, psyche you out and might get you injured. If your flexibility is right on the money, you should be able to assume the optimal starting stance, but with difficulty. If the going gets tough on the way down, you will have no trouble going up!

Dr. Judd: So flexibility is a powerlifter's enemy?

Pavel: EXCESSIVE flexibility, Judd. Not enough is even worse than too much. Soviet researcher and weightlifting coach R.A. Roman . . .

- Books by R.A. Roman and others available here:

http://www.dynamicfitnessequipment.com/category-s/1823.htm

. . . determined that an athlete loses 15% of his deadlifting strength when he pulls with a rounded, rather than a flat back. Have you noticed how extremely arched Russian Olympic weightlifters' backs are when they clean or snatch?

Dr Judd: Most athletes believe that the inability to arch means you have weak spinal erectors.

Pavel: Could be, but some lifters cannot hyperextend their backs to save their lives with 135. That's inflexible hamstrings, my friend.

Dr. Judd: So how much flexibility does a powerlifter need?

Pavel: Just a little more than necessary to lift with good form. For example, your hamstrings need to be flexible enough to maintain a tight arch in the 'hole' in the squat and at the start of the deadlift. It is essential for performance and safety. A properly arched spine can support 10 times more weight than a straight one, and even more than a rounded one. Ever heard a disc blow out? Sounds like a high tension cable going "boink!"

Dr. Judd: So you don't need to stretch your hamstrings to the point where you can tie your shoes with your teeth?

Pavel: Anything beyond what is absolutely necessary to maintain good form is detrimental.

Dr. Judd: In recent years sports teams have become interested in testing their athletes' flexibility. What is your opinion of the standard flexibility tests that are being used to measure this component of fitness by sports teams?

Pavel: Worthless. I once showed a Tampa Bay 'Buccaneer' how to cheat on the NFL sit-and-reach test, because it is as relevant to his ability on the football field as a chess gambit. I repeat, flexibility is very specific. Flexibility developed with one exercise does not always improve the range of motion of the same joint when tested on other exercises. In one study a group of subjects trained the toe-reach standing, and the other seated. Those who stretched in the seated position did not do well when they were tested standing. The other group did well on both tests. If a stretch does not improve your sport's functional flexibility - ditch it. In other words you should use flexibility exercises that are directly related to the sports skill you are going to perform.

Dr Judd: So you can be too flexible in some areas and inflexible in others?

Pavel: Precisely. Flexibility is highly specific in speed, the joints tested, and even the body position. For instance, a great ability to bend over and touch your toes does not automatically give you a great arch for the deadlift, even if your back is strong.

Dr. Judd: What would?

Pavel: I have modified on of Louis Simmons' exercises into a very effective stretch. Sit on the floor with your legs straight. Your feet should be as wide apart as pointing in the same direction as your squat and/or deadlift most of the time. Once in a while, vary the degree of hip abduction, how wide your legs are spread, and hip rotation, where your toes are pointed: Up, in, or out. This will help to keep your inner and outer hamstrings, semitendinosus with semimembranosus, and biceps femoris, balanced.

Hold a barbell low on your back, where you hold it in a power squat. If you keep it high, the bar will roll down your neck later in the stretch. The bar should be very light: 10% of your squat or dead at most. Even for Ed Coan, 95 pounds will do. Inhale as deep as possible and tighten every muscle in your body, while digging your heels hard into the floor. Hold your breath and tension for a few seconds, then suddenly let all the air go with the tension. You will drop and fall forward, thanks to the weight on your shoulders. Keep your toes pointed in the direction you chose in the beginning, be it in, up, or out. If they just fall out when you relax, have a training partner hold them in place or wedge them somewhere. Inhale and tighten again and repeat. When you tighten, make sure that you stay down and do not decrease the stretch by lifting the bar.

Dr. Judd: Do you need to keep your back flat or arched throughout the stretch to focus on the hamstrings?

Pavel: No. It is a back stretch too. Besides, unless you are already very flexible, and I bet your readers are not, your hamstrings will get a fantastic stretch even if you do not make an effort to isolate the movement in the hip joint.

Dr. Judd: It looks like this stretch could be very effective in rehabilitation from back and hamstring injuries.

Pavel: I believe so. If you are injured, please bring this stretch to the attention of your chiropractor or doctor.

Dr. Judd: Why shouldn't a lifter use a heavier weight if he feels like he can?

Pavel: Unlike in the squat and dead, where the weight is held up by the back muscles, in the relaxed phase of this stretch the load is supported by the lower back ligaments. A heavy weight could stretch the ligaments which will weaken your back. If you want extra resistance, have your training partner push down on the bar steadily while you are tensing. He should let you go - immediately! - when you relax and the load shifts from the muscles to the ligaments. Otherwise, you could get hurt.

Dr. Judd: Can a powerlifter increase his total by improving his flexibility in other areas?

Pavel: You bet. A good arch will help the bench big time. It will shorten the distance you have to press by a few inches and pre-stretch your pecs. You will bench more, guaranteed. If you are not build like a fire hydrant, a good arch is your only chance for a world class bench. Have you seen the arch of Irina Krylova from Russia? You could park a truck under her back. By the way, this skinny lady holds all time historical bench press records in two weight classes.

For a powerlifter it could mean the difference between being good or great. I'm serious; the information in the text is that significant. It is scholarship that is extremely esoteric.

Tsatsouline's authority springs partly from personal experience. Raised in Latvia of Russian parentage, Pavel got interested in flexibility training when he took up kick boxing. His parents were very encouraging. Pavel's father, Vladimir, is a retired Soviet Army officer and a passionate athlete. Swimming, boxing, judo, skiing, running, fencing, you name it, he's done it. Pavel's mother Ella is a former professional ballerina. When she was a kid studying at a ballet school, she was the most feared street-fighter in the neighborhood. Ella would deal out quick justice to the local punks with rapid-fire kicks in the face, years before karate was introduced to Europe and America.

Pavel Tsatsouline studied English at the Institute of Foreign Language in Minsk, Belarus (in what used to be the USSR) before receiving a degree in coaching and sports physiology at from the Physical Culture Institute (IFK). He served as physical training instructor for close to two years in Spetsnaz, with the Soviet Special Operation Forces. In Spetsnaz, he did his time near Moscow and in the Artic, in the diversionary reconnaissance detachment of the Red Banner Northern Fleet. Having to fight three or four men with your hands tied behind your back as a part of hand to hand combat training encouraged good flexibility.

"I have trained Soviet commandos to do splits in three to six months - whether they wanted to or not," quips Tsatsouline. "Now, that I have turned into a capitalist running dog, I can teach Americans how to stretch too. When I'm done with you, you will have the flexibility of a mutant. Or else." Yes! He is extremely humorous, but he is also eminently confident. Talking with him it is evident that he is a man who believes in himself and what he is doing.

Tsatsouline is not exactly a slouch as an athlete either. He started lifting weights to get stronger for fighting, but got the iron bug and eventually earned a National ranking of Master of Sports in kettlebell lifting, an ethnic Russian sport where you lift these big metal balls with handles for reps (this was written in 1998 . . . how different this is now!) I have witnessed such competition - it takes a MAN!

Still, it is his brain, not his brawn, that is most impressive. In my opinion it won't be long before he revolutionizes the field of flexibility. "Most Western flexibility experts," Tsatsouline states, "do not know enough physiology to have sex. You are far better off not stretching at all than following their advice. I'll fix it." I'm convinced Pavel Tsatsouline will do just that.

What follows is a two part (second part in another post to follow) exclusive Powerlifting USA interview on the subject of . . . .

The Powerlifter and Flexibility, Part One

an Interview with Pavel Tsatsouline

by Judd Biasiotto (1998)

Dr. Judd: Let's start by defining our terms. What precisely is flexibility?

Pavel: In athletic terms, it's the ability to perform your sports techniques through the required range of motion efficiently and without joint stress.

Dr. Judd: I once said that it would probably be easier to find a legitimate television evangelist than a powerlifter who can touch his toes without bending his knees. Isn't the lack of flexibility a major problem for powerlifters?

Pavel: Hell, no. When you stretch, you desensitize your stretch reflex. This reflex is what puts a 'spring' into your movement. A muscle that has been sharply stretched generates more force than a static muscle. To appreciate the difference try pitching a baseball without a windup or squatting from the low pin in the power rack. When you become more flexible, the muscle has to be stretched further and faster before the stretch reflex fires, or rather sizzles. As a result, you have to do most of the lifting on your own steam, without the extra boost of a reflex contraction.

Dr. Judd: That's interesting because most old-timers instinctively avoided stretching, feeling that they could lift more weight if they stayed "tight."

Pavel: They were right, up to a point. Why do you think Russian Olympic weightlifters avoid exercises that promote excessive flexibility of the muscles surrounding the hip and knee joints? Too much flexibility there makes the lifter sink too deep when he is getting under the weight. The same is true in powerlifting. You do not get extra points for squatting ass to the floor.

Dr. Judd: What if a lifter can't squat deep enough?

Pavel: I designed a special stretch for that. After I showed it to 900-lb squatter, Dr. Fred Clary . . .

Fred Clary

. . . many lifters from the Twin Cities Gym in St. Paul, Minnesota, picked up on it. Hold a light barbell, 95 to 135 pounds, over your head in the position for the press behind neck lockout.

Dr. Judd: Why not hold the bar on your back?

Pavel: It's too easy to cheat by bending over and rounding your back. When the bar is overhead, you are forced to keep the arch and stay upright!

Dr. Judd: Why the unusual breathing pattern?

Pavel: There is a relationship between muscular tension and your breathing patterns, the pneumo-muscular reflex. Lifters take advantage of it unknowingly. They increase their muscular tension by inhaling to the hilt before the attempt. In stretches we use the reflex to relax the muscles beyond what could be achieved by just 'ordering' them to relax.

Dr. Judd: Would excessive flexibility negatively affect the other two powerlifts?

Pavel: You bet. In the bench you will not be able to effectively store the elastic energy from the descent for the ascent. You might as well press from a dead stop in the power rack! Also, you might get red-lighted. For the same reason - the inability to keep the tension - the bar is likely to sink into your chest during the pause.

Dr. Judd: And the deadlift?

Pavel: If you are too flexible, you will lack tension at the start of the pull. That will limit your poundage, psyche you out and might get you injured. If your flexibility is right on the money, you should be able to assume the optimal starting stance, but with difficulty. If the going gets tough on the way down, you will have no trouble going up!

Dr. Judd: So flexibility is a powerlifter's enemy?

Pavel: EXCESSIVE flexibility, Judd. Not enough is even worse than too much. Soviet researcher and weightlifting coach R.A. Roman . . .

- Books by R.A. Roman and others available here:

http://www.dynamicfitnessequipment.com/category-s/1823.htm

. . . determined that an athlete loses 15% of his deadlifting strength when he pulls with a rounded, rather than a flat back. Have you noticed how extremely arched Russian Olympic weightlifters' backs are when they clean or snatch?

Dr Judd: Most athletes believe that the inability to arch means you have weak spinal erectors.

Pavel: Could be, but some lifters cannot hyperextend their backs to save their lives with 135. That's inflexible hamstrings, my friend.

Dr. Judd: So how much flexibility does a powerlifter need?

Pavel: Just a little more than necessary to lift with good form. For example, your hamstrings need to be flexible enough to maintain a tight arch in the 'hole' in the squat and at the start of the deadlift. It is essential for performance and safety. A properly arched spine can support 10 times more weight than a straight one, and even more than a rounded one. Ever heard a disc blow out? Sounds like a high tension cable going "boink!"

Dr. Judd: So you don't need to stretch your hamstrings to the point where you can tie your shoes with your teeth?

Pavel: Anything beyond what is absolutely necessary to maintain good form is detrimental.

Dr. Judd: In recent years sports teams have become interested in testing their athletes' flexibility. What is your opinion of the standard flexibility tests that are being used to measure this component of fitness by sports teams?

Pavel: Worthless. I once showed a Tampa Bay 'Buccaneer' how to cheat on the NFL sit-and-reach test, because it is as relevant to his ability on the football field as a chess gambit. I repeat, flexibility is very specific. Flexibility developed with one exercise does not always improve the range of motion of the same joint when tested on other exercises. In one study a group of subjects trained the toe-reach standing, and the other seated. Those who stretched in the seated position did not do well when they were tested standing. The other group did well on both tests. If a stretch does not improve your sport's functional flexibility - ditch it. In other words you should use flexibility exercises that are directly related to the sports skill you are going to perform.

Dr Judd: So you can be too flexible in some areas and inflexible in others?

Pavel: Precisely. Flexibility is highly specific in speed, the joints tested, and even the body position. For instance, a great ability to bend over and touch your toes does not automatically give you a great arch for the deadlift, even if your back is strong.

Dr. Judd: What would?

Pavel: I have modified on of Louis Simmons' exercises into a very effective stretch. Sit on the floor with your legs straight. Your feet should be as wide apart as pointing in the same direction as your squat and/or deadlift most of the time. Once in a while, vary the degree of hip abduction, how wide your legs are spread, and hip rotation, where your toes are pointed: Up, in, or out. This will help to keep your inner and outer hamstrings, semitendinosus with semimembranosus, and biceps femoris, balanced.

Dr. Judd: Do you need to keep your back flat or arched throughout the stretch to focus on the hamstrings?

Pavel: No. It is a back stretch too. Besides, unless you are already very flexible, and I bet your readers are not, your hamstrings will get a fantastic stretch even if you do not make an effort to isolate the movement in the hip joint.

Dr. Judd: It looks like this stretch could be very effective in rehabilitation from back and hamstring injuries.

Pavel: I believe so. If you are injured, please bring this stretch to the attention of your chiropractor or doctor.

Dr. Judd: Why shouldn't a lifter use a heavier weight if he feels like he can?

Pavel: Unlike in the squat and dead, where the weight is held up by the back muscles, in the relaxed phase of this stretch the load is supported by the lower back ligaments. A heavy weight could stretch the ligaments which will weaken your back. If you want extra resistance, have your training partner push down on the bar steadily while you are tensing. He should let you go - immediately! - when you relax and the load shifts from the muscles to the ligaments. Otherwise, you could get hurt.

Dr. Judd: Can a powerlifter increase his total by improving his flexibility in other areas?

Pavel: You bet. A good arch will help the bench big time. It will shorten the distance you have to press by a few inches and pre-stretch your pecs. You will bench more, guaranteed. If you are not build like a fire hydrant, a good arch is your only chance for a world class bench. Have you seen the arch of Irina Krylova from Russia? You could park a truck under her back. By the way, this skinny lady holds all time historical bench press records in two weight classes.

Dr. Judd: Don't back hyperextensions hurt your spine?

Pavel: Conventional stretches like the 'cobra' or the 'bridge' which jam your spine - do. My stretch is much safer and more effective because it 'elongates' the spine opening up the vertebrae and giving the discs and facet points more room to play.

Dr. Judd:

Will you describe this stretch?

Pavel: You need a curved padded surface to distribute the stress evenly throughout the spine, rather than jam it in one spot. A gastroc-ham-glute-raise machine, a pommel horse, or a Swiss ball will do. Standing with your back towards the pad inhale deeply and 'grow', separating the vertebrae. Still holding your breath, lean back and try to 'wrap' your back around the pad. Relax suddenly, letting your air out, and drop down an inch or so. If you are top heavy, have your training partner hold your feet down. Inhale and tighten up again and continue to the drill. If you experience pain in your back, you are doing the stretch wrong.

Dr. Judd: When should powerlifters do this stretch?

Pavel:Do a couple of sets before benching. You will feel a lot more stable when you set up and your benches will go up much easier.

Dr. Judd: Can you recommend any stretches to decompress the spine from heavy lifting?

Pavel: Hanging from a pullup bar is good. To make it awesome, take advantage of the pneumo-muscular reflex, as in my other stretches. Inhale as deep as possible and tighten every muscle in your body, making sure that you do not pull up higher. Hold your breath and tension for a few seconds, then suddenly let all the air go with the tension. You will drop, sort of getting taller. Repeat. Do the drill after lifting. Performing the hang before the arching stretch for the bench will make the latter even more effective by opening up the vertebrae.

Dr. Judd: Any more suggestions on how to help the squat and deadlift?

Pavel: Sure, with the right method. I'll drop you in a split in a few months if I am in the evil mood; sumo is a piece of cake.

No comments:

Post a Comment