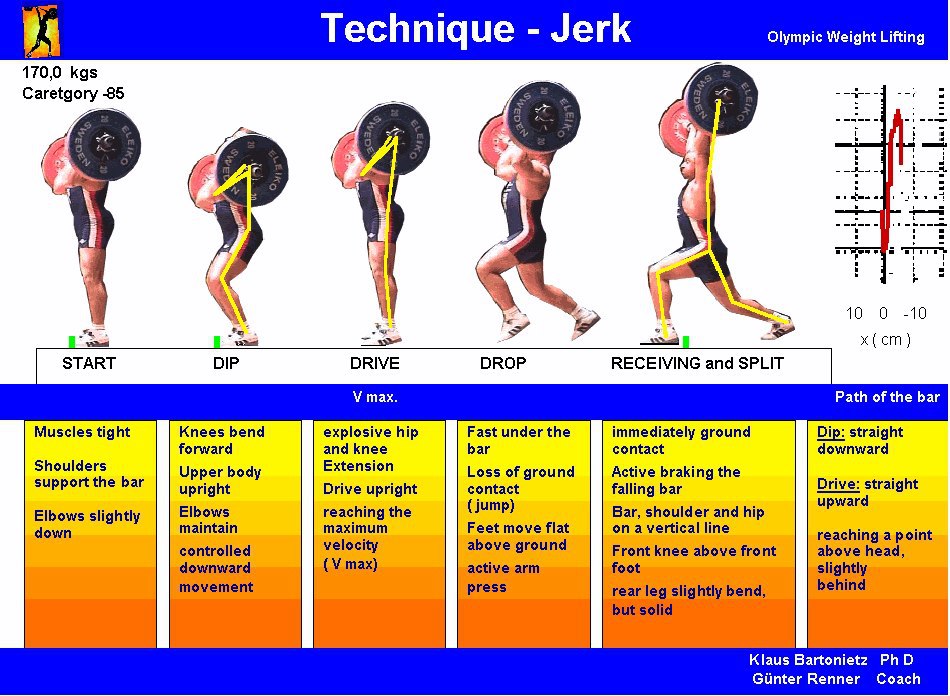

The iron community heard a certain amount of talk lately about the value of speed/strength training for athletes in explosive-oriented sports such as shot putt, Olympic weightlifting, football and sprinting. Clearly, if an athlete must be able to accelerate rapidly for his event, it makes sense to include movements involving rapid acceleration and other forms of speed work in training. This style of training, however, may also be beneficial to the bodybuilder.

Because many bodybuilders may be unfamiliar with the mechanics of speed/strength exercises in general and variable-velocity training in particular, why not take a moment and explore these two modes of weight training and discover what they might contribute to your routine?

As the term "speed training" implies, the major objective is to consciously teach the muscles to contract as rapidly as possible within a set period of time, thus enhancing reaction time while recruiting more fast-twitch, anaerobic muscle fibers -- those fibers that are most often associated with hypertrophy. General recommendations are that the time frame should be anywhere from 20 to 30 seconds with a poundage that allows you to do 12 to 20 repetitions as quickly as possible.

Needless to say, this type of training is totally rigorous. Because your muscles are forced to move faster than they are accustomed to, entire bands of fibers left unstimulated by the slow-and-steady tempo get a most dramatic and searing excitation, meaning that the appropriate muscles and central nervous system respond accordingly and adapt to new and greater types of exercise. In effect, you increase the "educational capacity" of the organism by varying the curriculum to include differing -- rather than constant -- velocities.

A weekly session of this sort of training would benefit any bodybuilder, especially those who have difficulty adding size. If you work out at the same tempo month and month, how can you expect to stress all of the various fibers within a muscle? You can't. So you should mix not only sets and repetitions, but also the rhythms you use.

Not all muscles of the body, however, respond equally well to this slash-and-burn training style, primarily because the element of intensity is so high -- you must generate tremendous forces in order to keep that bar humming. In general, speed training is tailor-made for large muscles, such as the quadriceps, latissimus dorsi and pectoralis major, because these exercises call upon the primary leverages of the body. By comparison, areas such as the deltoids, biceps and triceps are far weaker, so their contractile abilities are less.

Use speed training for major lifts such as the squat, bench press and row. But before you even think of doing a few speed sets (three should suffice), be sure to do a thorough warmup consisting of some light calisthenics, relevant stretching and a few easy preliminary sets of the movement itself.

When you are ready, use a weight that's about 60% of what you would use on a regular 10-rep set. For example, if you can squat 300 x 10, figure on using 180 or so for your "flame out" sets. And do have on of your trusted training partners time you, or time yourself for 30 seconds so you can see just how many deep ones you can burn through in this time frame. And burn you will! Many athletes crap out after the second set of such hell, leaving the third set on the platform.

Another similar concept is known as variable-speed rep training. The name says it all here: You intentionally vary the speeds, or rates, at which you lift. Using the squat again as an example, let's assume that you're still a 300 for 10 chap. In this case you will squat with no more 105 or 115 max, but you will shoot for a total of 50 to 60 repetitions, which means a whole lotta shakin' will be goin' on.

Do the first 10 reps in slow, controlled style, head level and back straight. Then do the next 10 as rapidly as your legs will allow -- in other words "sprinting." You do the third 10 in slow controlled style once again, and so on until you have completed the full 60 reps. By changing the pace you during the set you expose the muscles to different kinds of contractions and do what aerobic athletes call intervals.

Rest? Ideally, you should do all 10 of each distinct speed without pausing so that the proper system gets full benefit. Although you should try to do the first 20 without a pause, at the end of each 10 after that go ahead and help yourself to some deep breaths of air. This form of variable training is one of the toughest forms of training you will ever endure.

For the upper body give this method of madness a whirl on your benches, but reduce the reps to 25 to 30 and take them in groups of five slow/five fast. Do your best on the slow ones to maintain control of the resistance at all times -- if you can't maintain control then the weight is too heavy. Sticking to this rule will prevent you from injuring your chest or shoulder region. And do be an intelligent mate and have some form of spotting ready just in case things get hectic.

A weekly session of this sort of training would benefit any bodybuilder, especially those who have difficulty adding size. If you work out at the same tempo month and month, how can you expect to stress all of the various fibers within a muscle? You can't. So you should mix not only sets and repetitions, but also the rhythms you use.

Not all muscles of the body, however, respond equally well to this slash-and-burn training style, primarily because the element of intensity is so high -- you must generate tremendous forces in order to keep that bar humming. In general, speed training is tailor-made for large muscles, such as the quadriceps, latissimus dorsi and pectoralis major, because these exercises call upon the primary leverages of the body. By comparison, areas such as the deltoids, biceps and triceps are far weaker, so their contractile abilities are less.

Use speed training for major lifts such as the squat, bench press and row. But before you even think of doing a few speed sets (three should suffice), be sure to do a thorough warmup consisting of some light calisthenics, relevant stretching and a few easy preliminary sets of the movement itself.

When you are ready, use a weight that's about 60% of what you would use on a regular 10-rep set. For example, if you can squat 300 x 10, figure on using 180 or so for your "flame out" sets. And do have on of your trusted training partners time you, or time yourself for 30 seconds so you can see just how many deep ones you can burn through in this time frame. And burn you will! Many athletes crap out after the second set of such hell, leaving the third set on the platform.

Another similar concept is known as variable-speed rep training. The name says it all here: You intentionally vary the speeds, or rates, at which you lift. Using the squat again as an example, let's assume that you're still a 300 for 10 chap. In this case you will squat with no more 105 or 115 max, but you will shoot for a total of 50 to 60 repetitions, which means a whole lotta shakin' will be goin' on.

Do the first 10 reps in slow, controlled style, head level and back straight. Then do the next 10 as rapidly as your legs will allow -- in other words "sprinting." You do the third 10 in slow controlled style once again, and so on until you have completed the full 60 reps. By changing the pace you during the set you expose the muscles to different kinds of contractions and do what aerobic athletes call intervals.

Rest? Ideally, you should do all 10 of each distinct speed without pausing so that the proper system gets full benefit. Although you should try to do the first 20 without a pause, at the end of each 10 after that go ahead and help yourself to some deep breaths of air. This form of variable training is one of the toughest forms of training you will ever endure.

For the upper body give this method of madness a whirl on your benches, but reduce the reps to 25 to 30 and take them in groups of five slow/five fast. Do your best on the slow ones to maintain control of the resistance at all times -- if you can't maintain control then the weight is too heavy. Sticking to this rule will prevent you from injuring your chest or shoulder region. And do be an intelligent mate and have some form of spotting ready just in case things get hectic.