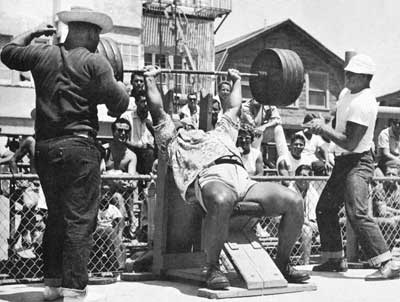

Bill West, left, spotting Steve Merjanian

Bill West, left, spotting Steve Merjanianphoto courtesy Laree Draper

http://www.davedraper.com/index.html

George Frenn, Power Lifter

by Armand Tanny (1966)

“Group Firing”, “Receptor Principle”, “Body Leverage”, “Change of Heart Syndrome”, “Base of Support”, “Labyrinthian Principle” – these dazzling terms tossed around by a far-out athlete characterize the space age technique of weight training. Exalted by enthusiasm, bursting with facts, figures and muscles, saturated with education, possessed of a fiery ambition that seems the natural outcome of bubbling health, George Frenn, Power Lifter, Hammer Thrower and student of Physical Education, is the happy and precise combination of all things that go into making a space age champion. At 5’11”, weighing 244, he has the compact look of featherweight and moves with a coordination and speed directed by a soft of built in electronic circuitry. Hal Connelly, Olympic Hammer Throw Champion, who gave George his start six years ago, says this about his precocious student: “After seeing all the other I would say George Frenn has the best chance of being the greatest hammer thrower in the world.” But when George is not training for the hammer, he is totally involved in power lifting. “My whole purpose in power lifting is to improve my hammer throw,” says George. In the process he won the Southern California Power Lift heavyweight title for 1966, and is aiming for the bigger contests. A practical competitor, however, he views the behemoths of power lifting with alarm: Gene Roberson, 280: Pay Casey, 280; Terry Todd, 345. “How can I compete with these big men,” he says. “The heavyweight classification is ridiculous. Unless they establish a two hundred and fifty pound class, I will probably wrap up power lifting when I make an eighteen hundred total.” It is more of a lament than a complaint, and it is justified. But when one studies the nature of this man a bit closer, one realizes with a strong hunch that he just might five these heavies a very bad time of it.

Before he started to train with the power lift group West Side Barbell Club operated by Bill West – that was a year ago – he had trained mostly alone for four years in his own garage. But he was dogging the ’64 Olympics then, and hammer throwing occupied him. For long stretches he didn’t power lift at all. Only in the past year has his great potential become apparent. By the time his best training lifts reach print – Bench Press 430, Squat 705, Dead Lift 665 – he will probably have made ancient history of them. Still growing at 24, he honestly believes he has found the secret of power lifting. Part of it could be his heavily structured frame. His thigh measures 28 ½ and just above the knee, 23, uncommonly large, a kind of structure that supports his “Body Leverage” theory. Mainly his success combines hard work with applied physiological and psychological principles.

The “Receptor Principle” particularly fascinates George. It puts lifting on a higher level of awareness he believes. Only a small percent of available muscle fibers that make up a particular body of muscle are activated in a simple muscle contraction. The strength of the contraction depends on how many fibers contract at the same time. “Group Firing”, as it is called, can be controlled largely by conscious thought. It becomes a confidence game. Simply telling yourself the weight is heavy and that you must lift it doesn’t usually work. The muscle must be tricked. Take the classic case of the 120 pound woman who lifted the end of an auto off her injured child. Fierce motivation propelled her. Muscle can be tried into making super lifts. The available nerve channels are there, but discovery takes searching. Conscious searching. Discovery is by chance. Take the case, as another example, of the man who saved twelve thousand dollars over a period of years from money he had found on the streets, only because he looked for it. How does the brain receive the impressions (Receptor Principle) that will send out the message to the muscle to contract stronger (Group Firing)? One was is the touch system developed by chance by George and Bill West working together. The hand of the training partner on the bar or the body during a limit attempt offers the additional “power of suggestion”. Once when George was struggling to deadlift 710 off the blocks Bill got him past a sticking point by lightly placing his fingers under the bar. A sharp slaps on hips in the low positions of a heavy squat will also work wonders. They have named it the Assistant Method. Then, of course, there are cheating movements, less delicate than the power of suggestion method, in which you take the muscle by the collar and force and overload on it.

By applying these systems, George is continually outdoing himself. The old equation where 450 – 5 is automatically equal to a single with 500 ceases to be valid. In his own case a wide breach exists between his maximum repetitions and a single heavy lift. Reps act primarily as warm ups or as a finishing flush. His workouts are made of single attempts, the accepted cannon of all power lifting these days. George has done 600 – 8 reps squat, a phenomenal display of power itself; however, his best single is far superior 705.

George analyzes that a heavy lift is based on three considerations: 1. Leverage; 2. Size; 3. Number of group firings. He has the fire power of a battleship, but he has not yet determined whether better leverage come from bigger muscles or blued up bodyweight. It appears he will pursue whatever is necessary to make greater lifts. Obviously 5’10” Gene Roberson, at 280, is well endowed with what George categorizes as “Body Leverage”. Roberson’s lifts bear that out: Bench Press 490, Squat 731, Dead Lift 720. Even at his own 5’11”, 244, George considers himself a slim Jim among power lifters.

He didn’t start as a weakling, however, for at 18, after brief training he deadlifted 510. Connelly taught him the basic exercises – bench press, squat, high pull, military press, power clean. He practiced reps at first, good for size and shape, also necessary for hammer throwing, but they did little to increase his strength. He was only gaining about five or ten pounds on each lift every year. Up to the time of the ’64 Olympics it didn’t matter, he was too concerned with the hammer. He practiced heavy squats on the assumption he would throw the hammer 210 if he could make a 550 squat. He was correct. Early in ’65 he started to train the West Side Barbell Club and under the guidance and encouragement of Bill West he began to learn the meaning of training on single attempts. Bill had the empirical experience. He understood the value of low reps with heavy weights. George, in his school work, saw how medical and physiological experiment confirmed this experience, and from then on they were given to endless discussions and revisions of methods. They can now sup it up with one evident truth: Under the right conditions anything is possible. One of these conditions concerns the individual’s mood. Called the “Change of Heart Syndrome”, mood effects performance. Mental depression hinders effort. Peace of mind, then, becomes as important as the act of training. Nor is peace of mind static. Like heavy single attempts, peace of mind comes hard, but with continual striving, it comes.

Voluable and articulate, a natural talker, George will monologue with himself when under a heavy weight. He apparently is two people, one the easy going human, the other the hard driving athlete. The former needs a lot of persuasion. So huffing and puffing, like the proverbial choo-choo train climbing the mountain – “I think I can . . . I think I can. . . ” – George mutters all kinds of blandishments to that self. So convinced is he that state of mind governs performance, he will start thinking a month in advance of a contest on an intended lift. Although he may use only 600 in training, his mind is on the projected 700 of the contest attempt.

To be on the safe side he prefers group training, having three spotters on his heavy attempts and two on the lighter ones. His own secret is not day to day progress because his own nature is such that his strength varies widely at times from one workout to the next. He refers to single heavy attempts. Other than that he abides by a rule: Break a record every workout. Become conditioned to successful attempts. This can mean an added rep or an added pound almost anywhere where you have never done it before. He cites as a delicious example of total mental blackout Dave Davis’ recent workout, a record of failures, the inability to do a single squat with as little as 400 making a 555 squat in a contest the week before. “That should set Dave back three months,” he laughs. But Dave is a contest lifter, and anything can happen.

To go even farther on the conditioned response idea, a competition atmosphere, a George’s insistence, was set up at the West Side Club where now they use only standard Olympic barbell plates for training. Bill had to discard all his exercise plates. “It’s strictly a mental thing,” says George. “You must remember that emphasis is on maximum lifts at all times. You have to channel not only effort but also training conditions to the maximum effort and conditions that exist in and at a contest.”

Never easy, he fights to avoid foolish training challenges. They only end up in torn muscles and bad backs. He has tantalizing knowledge of training research. For example, five repetitions with two thirds maximum weight will maintain maximum strength. Also that running is an absolute necessity in any kind of training. Not long runs, but rather short 50 yd. sprints. George does 10 – 50 yd. sprints twice weekly. The reason: the cardio-vascular system must be kept elastic. The intra-thoracic pressure is enormous in heavy single weightlifting attempts. The heart and blood vessels must be ready for this force. He also swims and does stretching exercises, convinced that full flexibility helps rather than hinders strength. To be sure, strength is a product of the mind. Strength is triggered in the brain, not in tight muscles.

Another piece of applied physiology is the “Labyrinthian Priciple”. Medical research indicates that when the head is forward, the face down, an upset occurs in the middle of the ear that causes relaxation of the spinal muscles. By forcing himself to look up George can maintain the arch and rigidity of his back, the form necessary for both the squat and deadlift. He recalls the time at a contest when his final deadlift stuck half way, and suddenly realizing his head was down he threw it back as hard as he could which gave his spine arch, and the weight moved up again steadily to completion.

Another principle he makes full use of is the basic “Base of Support”. For example, he wraps the full length of a folded bed sheet around his waist before putting on his lifting belt. This, he reasons, increases the diameter of his midsection and gives him a more solid base of supporting the heavy squats and deadlifts.

At the moment he shares power lifting with school and hammer throw practice. He is working toward his master’s degree in physical education at Long Beach State College. He has made two hammer throwing tours of Europe. A rumor at large says he has made several foul throws over 240 feet. If he can straighten them cut, the world record could soon be his.

He makes heavy power workouts seem almost like play, a quality characteristic of big men with great strength who make heavy lifts seem effortless. To a certain extent this is due to an effort on his part to eliminate strain, to make all lifts as effortless as possible. “Lift as much as you can as easy as you can,” he says. “Success begets success.” This all seems to be part of the endless mental conditioning he strives for. George has hit the jackpot in strength, and he is making a frantic effort to hang to the ringing, magic flow.

His schedule:

Saturday – heavy

1. Bench Press

135 10 reps

225 5

295 4

320 2

360 1

285 5 flush

With pads

405 2

425 2

440 1

450 1

460 1

470 1

295 10 flush

2. Squat

135 10

225 5

325 5

425 4

525 3

565 2

600 1 or 2

635 4 singles

655 1

500 10 flush

3. Deadlift

225 6

315 5

415 4

500 4

550 3

575 2

620 1 or 2 singles

Note. For every squat rep he does one calf rep from the floor before returning the weight to the rack. A muscular calf gives leverage and strength to the squat.

Tuesday – light

Warmups same as Saturday

No deadlifting

1. Bench Press

After warmup sets

375 5 singles

295 10 flush

2. Squat

After warmups

575 5 singles

No flush

On either Wednesday or Thursday, on what he calls piddling days, he does special light work:

1. High Pulls with barbell

225 10

275 10

325 4 or 5

2. Tricep extensions – a few of any kind.

He has done 10 reps high pulls with 405 using wrist straps.

Article courtesy of Adrian Gomez

No comments:

Post a Comment